It looks like Hungary, like other Western countries, is going to host it share of Chinese police stations. Our Hungarian correspondent László sends this report.

The Curious Case of the Chinese-Hungarian Law Enforcement Summit

by László

“Chinese-Hungarian Law Enforcement Summit”?!

Astonishing. And ominous.

I mean, what the yellow-red hell?!

The Minister of the Interior isn’t supposed to be… interior?

“During the official meeting with his Chinese partner on 16 February 2024 in Budapest, Minister of the Interior Dr. Sándor Pintér stressed that the cooperation between the two countries is based on the guarantee of security and stability […]”

I could find no further information on what exactly it all means (which is strange in itself), so I can only guess… Nothing good for liberty, for sure — especially for Chinese expats.

“The two leaders signed agreements on strengthening law enforcement cooperation and joint patrols.”

Huh? Does it mean Chinese policemen in Hungary?

I’m quickly sending this last S.O.S. message before my Covid card turns red and my internet access gets blocked. Food donations are welcome, as Chinese AI systems won’t allow me and my family to do the grocery shopping, as soon as this letter gets published.

OK, for the time being that’s a joke — but how long before it isn’t?

Translation of the announcement published on the official website of the Hungarian government:

Chinese-Hungarian Law Enforcement Summit

The State Councilor of the People’s Republic of China, Minister of Public Security Wang Xiaohong, paid his first official visit to Hungary after the Chinese New Year.

During the official meeting with his Chinese partner on 16 February 2024 in Budapest, Minister of the Interior Dr. Sándor Pintér stressed that the cooperation between the two countries is based on the guarantee of security and stability, which are essential for the establishment and further development of comprehensive strategic cooperation.

With the visit of State Councillor Wang Xiaohong, the parties took an important step towards the development of relations between the Ministry of Public Security of the People’s Republic of China and the Ministry of the Interior of Hungary. The two leaders signed agreements on strengthening law enforcement cooperation and joint patrols.

During his visit to Hungary, the Chinese Minister of Public Security, among other things, familiarized himself with the structure and capabilities of the Hungarian counter-terrorism service and inspected the construction works of the Budapest-Belgrade railway line.

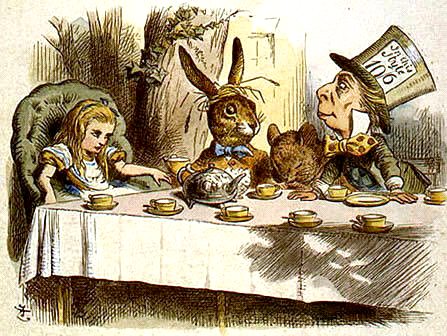

The tea itself contained certain extra plant matter amongst its leaves, which floated on the surface in the cup. This was strained off with a special shallow-bowled pierced ‘mote skimmer’. Enterprising silversmiths offered handsome silver skimmers with pretty patterns of piercing. At first the traditional Chinese porcelain spoon, on its own tray, would be handed round to be used for stirring. This was found to be rather cumbersome, so the teaspoon was created, around the 1790s, so that each drinker could have an individual stirrer. Once more the silversmith’s art came into its own with a choice of pretty designs. The teaspoon has ever since held its own as a useful innovation, and is now a standard item. Strainers, also produced in variety, enabled the hostess to prevent leaves from entering the cup; with their special bowls to rest on they joined the essentials on the tray, gradually displacing the mote skimmers.

The tea itself contained certain extra plant matter amongst its leaves, which floated on the surface in the cup. This was strained off with a special shallow-bowled pierced ‘mote skimmer’. Enterprising silversmiths offered handsome silver skimmers with pretty patterns of piercing. At first the traditional Chinese porcelain spoon, on its own tray, would be handed round to be used for stirring. This was found to be rather cumbersome, so the teaspoon was created, around the 1790s, so that each drinker could have an individual stirrer. Once more the silversmith’s art came into its own with a choice of pretty designs. The teaspoon has ever since held its own as a useful innovation, and is now a standard item. Strainers, also produced in variety, enabled the hostess to prevent leaves from entering the cup; with their special bowls to rest on they joined the essentials on the tray, gradually displacing the mote skimmers.