This is the seventh essay in an occasional series. Previously: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6

Requiem for a Culture

Part 7: The Traitresses of Roswell

The past is never dead. It’s not even past.

— William Faulkner, Requiem for a Nun, Act I, Scene III (page 80 in the Vintage paperback edition)

In the annals of the American Civil War, the story of the women of the Roswell cotton mill in Georgia is relatively obscure. I had never even heard of the incident until just a few days ago, when a talk was given at a meeting of the Sons of Confederate Veterans.

General Kenner Garrard, U.S. Army

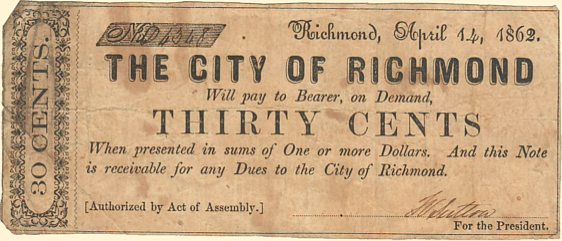

General Kenner Garrard, U.S. ArmyIn July of 1864, during the march on Atlanta, Union General Kenner Garrard burned the mills at Roswell in northern Georgia. The cotton mill in Roswell had been producing fabric for Confederate uniforms, plus tent cloth and other products destined for military use.

The next day, under General Sherman’s orders, General Garrard arranged for the deportation of about 400 civilians, most of them women and children. The women had worked in the mill, and were thus judged by General Sherman to have committed “treason”. They and their offspring were carried by wagon to Marietta, where they were loaded onto railroad cars and shipped north, first to Nashville, and then to Louisville. From there they were deported across the Ohio River into Indiana. Whatever processing they underwent after that was rudimentary; they were basically abandoned, and left to their own devices.

An undetermined number of the deportees died in transit under horrific conditions, and more died after arrival. Almost none of them are known to have ever made it back home, and there are very few records of what became of them.

During their travels they were guarded by Union soldiers, who were probably less bestial than Hamas mujahideen in the treatment of their charges, but still… One may assume that Union soldiers who were suffering from “sexual emergencies” took advantage of the opportunity presented by all those teenage girls in their care.

Also, given the privation those girls were to face in Indiana, it wouldn’t be surprising if many of them joined the ranks of the world’s oldest profession.

Why is it that there are so few historical accounts of what happened to the Roswell women?

The deportees were largely Scots-Irish, the descendants of immigrants who came to western Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia beginning in the early 1700s, and then migrated south along the Appalachians. In other words, they were the poorest of poor whites, commonly known as hillbillies or white trash. My guess is that they were illiterate, or nearly so, and thus never wrote any letters to their relatives back home. No journals or memoirs — they just disappeared into the poverty and chaos of southern Indiana, and were lost to history.

Before I get to more detailed information about the deportation of the mill workers from Roswell, I’d like to touch briefly on the absurd notion that by working in the mill they had committed “treason”.

It reminds me of a conversation I had a couple of years ago while manning a booth for the Sons of Confederate Veterans. Members in period uniforms with muskets had set up a mock encampment with a tent, etc., and next to it were selling Confederate-related merchandise from a small pavilion, which is where I was working.

One young white man came by the booth with a chip on his shoulder, and obviously wanted to argue with us. He wasn’t a Northerner. He was probably a transplant from further north in Virginia, but not a Yankee. I reported on the conversation not long after it happened, in the first post of this series:

Visitor: “I just want to know why you people think it’s a good idea to do this, to pay respect to traitors.”

Baron: “We’re here to honor our ancestors, who fought to defend the Commonwealth of Virginia. We were invaded, you know — just like Ukraine was invaded by the Russians.”

V: “But Ukraine is different. It was invaded by the forces of a completely different country.”

B: “Exactly. And Virginia was sovereign until 1865. Did you know that? It considered itself a sovereign state. You can see it in the printed materials from the time: ‘The Sovereign Commonwealth of Virginia’. Union troops came up the Shenandoah Valley, torching the fields, requisitioning food and supplies, and taking prominent citizens hostage for the good behavior of their fellow townsfolk. We were invaded, and we were defending ourselves.”

V: “Well, I have an ancestor who fought, and I don’t want to honor him. I don’t know anything about him, and I don’t want to know, because he was a traitor.”

It’s a peculiar idea, that someone who resists the invasion of a sovereign state might be considered a traitor to the invading country. Imagine, for example, a war between Prussia and the Kingdom of Saxony. Saxony was an independent, sovereign state until 1871, when it became one of the states comprising the newly-formed German Empire. Prior to 1871, if Prussia were to invade Saxony, it would be the duty of every able-bodied adult Saxon male to take up arms and resist the invader. If Prussia won the war, it might annex Saxony, or turn it into a vassal state owing fealty to the King of Prussia. But nobody involved, whether Prussian or Saxon, would have considered a Saxon who fought back against the Prussians to be a traitor to Prussia. The idea would have been ludicrous, and would never have been entertained.

The same is true of any Virginian who resisted the invasion of his sovereign state between 1861 and 1865. Or should be true, but we live in a degraded age in which language has been torqued beyond belief, and the ability to think logically about this and similar matters has atrophied.

The North won the war, and therefore got to write the terms of political arrangements afterwards. Among those terms was this: any citizen of the sovereign South who dared to resist Northern aggression was retroactively to be identified as a TRAITOR to an entity that didn’t exist before 1865. Dig it?

The paragraphs below are excerpted from “Charged With Treason: The Plight of the Roswell Women” from the American Civil War Forum:

At the time of the American Civil War, the four hundred women employed by the Roswell Mills were mostly of Scottish-Irish descent. As the mill increased in production, so did the number of people living in the area, but once the war was in full swing, the leading families of Roswell fled in advance of Sherman’s army, leaving the fate of the mills and their employees in the hands of Federal forces. Innocent civilians were left to fend for themselves and receive the entire brunt of Sherman’s wrath and vengeance.

Looking for a way to get his army across the Chattahoochee and thus into Atlanta, on July 6, 1864, Sherman sent General Garrard back upstream with orders to capture Roswell. In Garrard’s report to Sherman, he relayed that, “there were fine factories here. I had the buildings burnt, all were burnt. The cotton factory was working up to the time of its destruction, some 400 women being employed.” On July 7, 1864, Sherman wrote to General Garrard, “I repeat my orders, that you arrest all people, male and female, connected with those factories, no matter the clamour, and let them foot it under guard to Marietta, then I will send them by cars to the North.”

Thus the Roswell women were charged with treason and deported from the only homes they had ever known.

[…]

The women of the Roswell Mills and their children were kept in the open town square in the blistering heat of a Georgian July, before they were forced to march to Marietta. Roswell’s whiskey stores found their way into the hands of the Union guards and from that time on and during their escort to Marietta, the young girls of Roswell lived in a continual nightmare.

In 1860, forty per cent of the women living in Roswell were seventeen years old and younger. Therefore, at the time the Roswell Mills were burned to the ground, almost half of the population consisted of young girls on the cusp of womanhood. Along the way to Marietta, many of the women were forced to ride behind the cavalry men, which they hated. One Illinois soldier wrote home, “The employees (Roswell Mills) were all women and they were really good looking. We always felt that we had a perfect right to appropriate to our own use anything we needed for our comfort and convenience.” One Union officer found it necessary to move his troops a mile away from the women in order to control his men.

A northern newspaper correspondent reported on the deportation of the Roswell women, “Only think of it! Four hundred weeping and terrified Ellens, Susans, and Maggies, transported in springless and seatless army wagons, away from their loves and brothers of the sunny South, and all for the offense of weaving tent-cloth.”

Continue reading →

Mathieu Slama is a French political journalist and essayist who teaches at the Sorbonne. In the following video he discusses his vision of Europe as a cosmopolitan paradise where all citizens are identity-free, and where evil nationalism can gain no traction. He acknowledges that current events are trending against him, and specifically mentions Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán as representing the forces of identitarian reaction.

Mathieu Slama is a French political journalist and essayist who teaches at the Sorbonne. In the following video he discusses his vision of Europe as a cosmopolitan paradise where all citizens are identity-free, and where evil nationalism can gain no traction. He acknowledges that current events are trending against him, and specifically mentions Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán as representing the forces of identitarian reaction.