This is the third essay in an occasional series. Previously: Part 1, Part 2.

Requiem for a Culture

Part 3: The Battle of Staunton River Bridge

The past is never dead. It’s not even past.

— William Faulkner, Requiem for a Nun, Act I, Scene III (page 80 in the Vintage paperback edition)

The Roanoke River is a modest river at the bottom of a deep gorge where it flows out of Roanoke to the southeast. By the time it empties into Swan Bay and Albemarle Sound in coastal North Carolina, it is a broad expanse of slowly-moving water.

For a portion of its passage through Virginia, the Roanoke River inexplicably assumes a different name. According to Google Maps, it becomes the Staunton River where Cheese Creek joins the flow just below Altavista in Campbell County. It then resumes its former name where it widens out as it becomes the John H. Kerr Reservoir, a.k.a. Buggs Island Lake, between Charlotte and Halifax Counties. In reality, however, the two toponyms are not that clearly delineated — which name is used depends largely on local customs.

To make matters even more interesting, the name of the river, like that of the city of Staunton (which is nowhere near the river), is pronounced “Stanton” — one of many regional peculiarities of Virginia pronunciation.

In the middle of its term as the Staunton River, it is crossed by a railroad bridge that was strategically important to the Confederacy in the summer of 1864. At that time General Robert E. Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia were entrenched in and around Petersburg, where they were besieged by the Union Army commanded by General Ulysses S. Grant. The Confederates’ main supply route was a single railroad line that crossed the Staunton River from Charlotte County into Halifax County just south of Roanoke Station, nowadays called Randolph.

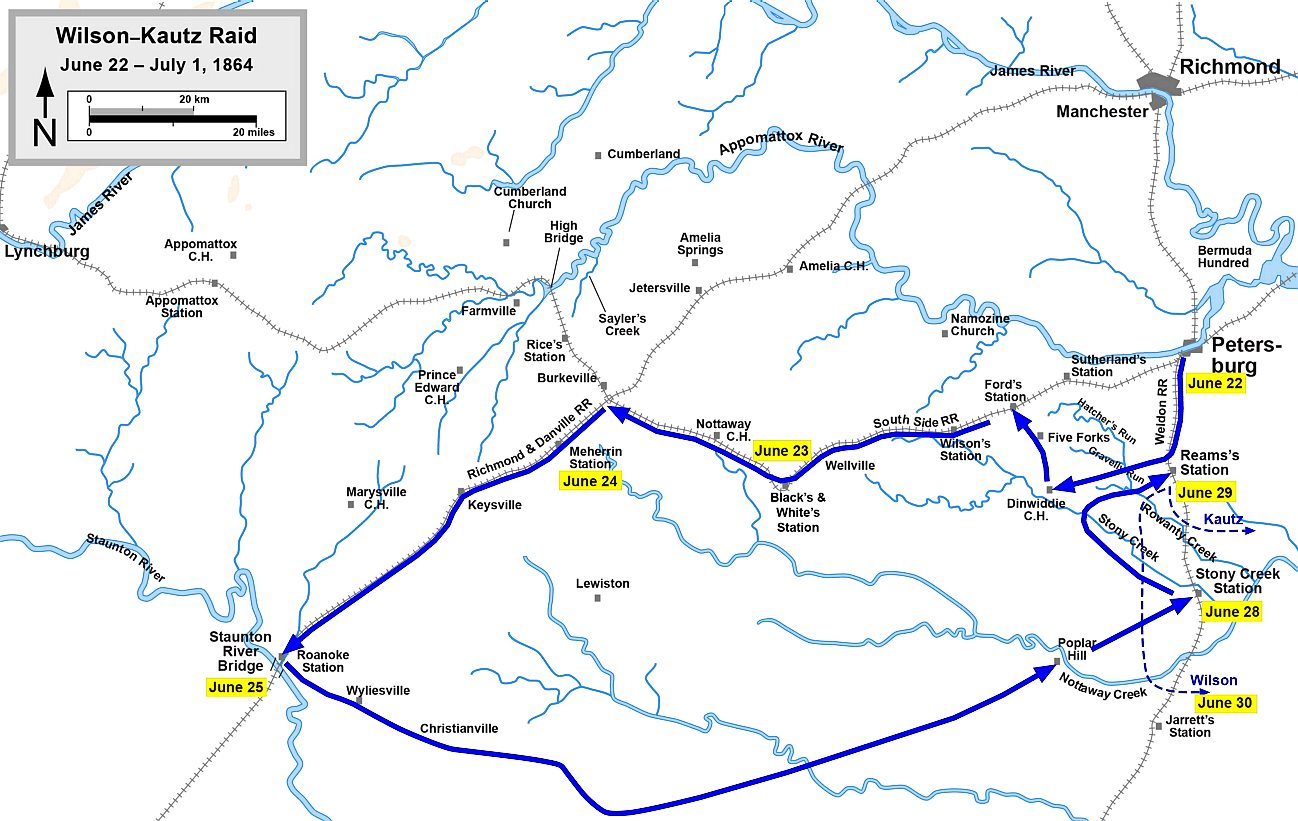

In late June General Grant ordered a raid on the railroad line. 5,000 cavalry troops led by Brigadier Generals James H. Wilson and August V. Kautz left the Petersburg area on June 22nd and proceeded west and south along the railroad, tearing up track and burning down stations. Their ultimate objective was to destroy the Staunton River Bridge.

Below is a map of the raid. It’s somewhat inaccurate in its details — for example, it puts Cumberland significantly to the south and west of its actual location. It also misspells “Nottoway”. Nevertheless, it’s a useful overall schematic diagram of events during the raid.

On June 23rd General Lee sent word to Captain Benjamin Farinholt, who commanded a battalion of reserves charged with defending the bridge, warning him that the Federals were about to come down hard on him, and ordering him to prevent the bridge from being destroyed. If the Union troops were able to get to the bridge even briefly, they would pour oil on its wooden structure and torch it.

Captain Farinholt’s situation was dire. He commanded a force of fewer than 300 soldiers, and had only six artillery pieces with which to confront the sixteen being fielded by the Northern cavalry.

That night he sent word out to the surrounding communities, asking for volunteers to help defend the bridge. Military-age men had already been siphoned off by conscription, so the captain was drawing on teenage boys and men over 45 to form hastily-assembled militias. In popular accounts written after the war they were referred to as the “Brigade of Old Men and Young Boys”.

The new arrivals were also augmented by 150 Confederate regulars from detachments stationed around the region. With the regulars added to the old men and boys, Captain Farinholt was able to deploy a force of 938 men — less than 20% of the size of the cavalry units bearing down on him.

The battle was joined on the afternoon of June 25th. As happened so many times during the Civil War, the South prevailed against a much larger Northern force. 42 Union soldiers (including several officers) were killed, 44 were wounded, and 30 were missing or captured, while Captain Farinholt’s men suffered 10 killed and 24 wounded.

The details of the battle make for inspiring reading. The excerpts below are from the Staunton River Battlefield website:

In June of 1864, Confederate General Robert E. Lee and his Army of Northern Virginia were engaged in a desperate defense of the city of Petersburg, Virginia. Victory for Lee depended upon a steady flow of supplies from the west and south, via the South Side and Richmond & Danville railroads. Union General Ulysses S. Grant knew that if these supply lines could be destroyed, Lee would have to abandon Petersburg. To accomplish this, Grant planned a cavalry raid to tear up the tracks of both lines and destroy the Richmond & Danville railroad bridge over the Staunton River.

The raid began on June 22, and was led by Brigadier General James H. Wilson and Brigadier General August V. Kautz. They left Petersburg with over 5,000 cavalry troops and 16 pieces of artillery. As they moved west, the Union raiders were closely pursued by Confederate General W. H. F. “Rooney” Lee and his cavalry. Although Lee’s troopers occasionally skirmished with the invaders, they were unable to stop their advance. During the first three days of their raid, Wilson’s cavalry tore up 60 miles of track and burned two trains and several railroad stations.

Just south of Roanoke Station (present-day Randolph) was a long, covered railroad bridge over the Staunton River, Wilson’s final objective. The bridge was defended by a battalion of 296 Confederate reserves under the leadership of Captain Benjamin Farinholt. On June 23rd, at 10 p.m., Captain Farinholt received word from General Robert E. Lee that a large detachment of enemy cavalry was moving in his direction to destroy the bridge and that he should “make every possible preparation immediately.”

Captain Benjamin Farinholt: “By the trains at 12 o’clock that night, on the 23rd, I sent off orderlies with circulars, urging the citizens of Halifax, Charlotte, and Mecklenburg to assemble for the defense of the bridge, and ordering all local companies to report immediately… On Saturday morning, the 25th, about 10 o’clock I had received, citizens and soldiers inclusive, 642 re-enforcement. Of these about 150 were regulars, organized from different commands, my whole command numbered 938 men.”

Though his numbers had been bolstered by volunteers, Farinholt was still badly outnumbered. He had only six pieces of artillery, four in the earthwork fort on the hill just east of the bridge, and two in a small fortification west of the bridge. Between these artillery positions and the river was a line of trenches, and across the bridge lay a semicircular line of hastily constructed but well-concealed rifle trenches. Captain James A. Hoyt with his two companies of regulars were on the east side of the bridge, and Colonel Henry Eaton Coleman’s “Old Men and Young Boys” were on the west side. Scouts and pickets were posted north of the bridge near Roanoke Station.

Captain Farinholt knew that his activities at the bridge were being watched by Union scouts who had arrived ahead of the main body of troops. To make them think that he was receiving reinforcements, Farinholt ordered an empty train to run back and forth between Clover Depot and the bridge, giving the appearance that fresh troops were arriving constantly.

As it turned out, the Union scouts were not the only ones fooled.

J. B. Faulkner: “…I happened to be one of Farinholt’s scouts that day. We were stationed on the same side of the river with Wilson’s forces on a high hill that overlooked the entire field. When we saw the [train] cars roll in and saw the men apparently disembarking, we felt sure that our men were being reinforced by every train.”

Mulberry Hill plantation was located on a commanding hill near the battlefield and the grounds of the house served as the Union headquarters and field hospital during the battle. It is said that Mrs. McPhail, the lady of the house, told the Federals that 10,000 Confederates lay in wait for them beyond the breastworks and that every train was bringing more.

Captain Benjamin Farinholt: “The enemy [Federals] appeared in my front about 3.45 p.m.… I opened up on them with a 3-inch rifled gun, but the shot, from some inexplicable defect in the gun, fell short of the mark. They were then within a mile of my main redoubt, and, taking possession of a very commanding hill, immediately opened with rifled Parrots and 12-pounder Napoleons …”

J.T. Easton, 17th Mississippi Regiment: “… they opened up with their field guns… The shells striking the thin roof of the bridge made a fearful racket, scaring some of the small boys into outbursts of weeping.”

Having arrived north of the bridge, General Kautz’s cavalry troops were dismounted and formed up to cross the open fields toward the bridge. They were receiving heavy fire from the Confederate artillery on the other side of the river. Colonel Samuel R Spear’s 1st D.C. and 11th Pa. approached along the east side of the railroad and Colonel Robert M. West’s 5th Pa. and 3rd N.Y. along the west side.

Colonel Robert M. West: “I formed an assaulting party and directed it up the embankment, in the hope that by a quick move we might obtain possession of the main bridge sufficiently long enough to fire it. The men tried repeatedly to gain a foothold on the railroad, and to advance along the sides of the embankment, but could not.”

Having finally reached a shallow drainage ditch some 150 yards north of the bridge, the Union troops organized for what was to be the first of four separate charges, all of them repulsed by the badly outnumbered Confederate forces. When the Union forces left the drainage ditch for their first assault on the bridge, they were met by intense fire from Col. Coleman’s old men and young boys and the regulars who had been hidden from view in their shallow trenches around the bridge.

Captain James A. Hoyt: “…the fatal ditch was an obstruction which they never passed again. The second charge was repulsed with equal gallantry, showing a determined resistance on our side, but it required longer time and heavier firing to drive them back. Then followed a longer interval between the charges… the third time the effort was made… they were no nearer the capture of the bridge than when they first came in sight of it.

“The sun was going behind the hills, but as yet there was no sign that General W. H. F. Lee had reached the enemy’s rear. His appearance on the scene would mean relief for our little band… when the Federals gathered for the fourth charge there were misgivings as to the result. On they came, however, and they were met with a galling fire of musketry, which grew even more furious as their lines came nearer It was during this charge that Lee and his division struck the rear-guard of the Federals, and they were given an opportunity of fighting in opposite directions.”

General James H. Wilson: “…the place was found to be impregnable. Finding that the bridge could not be carried without severe loss, if at all, the enemy being again close upon our rear, the Staunton too deep for fording and unprovided with bridges or ferries, I determined to push no further south, but to endeavor to reach the army by returning toward Petersburg… The march was therefore begun about midnight…”

Capt. Benjamin Farinholt: “At daylight, I advanced my line of skirmishers half a mile, and discovered that the enemy had left quite a number of their dead on the field. In this advance 8 prisoners were captured… Of the dead left on the field I buried 42, among them several officers. My loss, 10 killed and 24 wounded.”

For the 492 local citizens that made up the “Old Men and Young Boys” Brigade, the fight was over, and an important supply line had been protected for General Robert E. Lee and his army in Petersburg. They had proudly answered the call to arms and, in the face of overwhelming odds, distinguished themselves on the field of battle. Over the years, the stories about their victory on that hot summer afternoon at the bridge have been retold countless times and have become an important part of the proud heritage of Southside Virginia.

Another account of the battle may be read here.

There are almost no photographic records from the Battle of Staunton River Bridge, so I’ve used a modern photo for the header of this post. It was taken at the bridge this past summer during the annual commemoration of the battle. The people standing on the bridge are from the Sons of Confederate Veterans and the United Daughters of the Confederacy, along with some of their children.

The area around the Staunton River Bridge is very rural — even more so than my neighborhood. There are no significant towns within ten miles, and the nearest city (Lynchburg) is about thirty miles away.

There are many residents of the area who are descended from the members of the Brigade of Old Men and Young Boys who carried the day on June 25th, 1864. I wasn’t at the event this past June, but I wouldn’t be at all surprised if some of the people in the photo had ancestors who fought that day. Perhaps someone who was a 13-year-old boy at the time, one of those who wept when the Union shots struck the roof of the bridge, but who carried on anyway, and was a credit to his family.

Just think what pride one of those little boys must feel, whose great-great-great grandfather was there that day and served so honorably. A family memory like that, passed down from father to son, generation after generation, is a difficult thing to erase. The Woke brigades that now rule our culture are doing their best to wipe out such historical memories, but I can tell you from my experience in the Sons of Confederate Veterans that they are not being entirely successful. Our camp just welcomed a 13-year-old cadet, who stood there proudly next to his father the night he was sworn in.

I’ll wrap up this installment with a little piece of memorabilia. The image below shows the album cover for an old mono LP that I listened to over and over again when I was a kid:

My father was a Yankee and my mother was a Rebel, so I had feet in both camps, and listened to the songs from both sides with avid interest. As a child, my overall sentiment was that it was a good thing that the North won, because it ended slavery, which was bad. But I had plenty of respect for the Confederates — after all, my great-great-grandfather had served, and I’d seen old photos of my mother sitting on his knee when she was a toddler, and he was over a hundred.

That album came out during the run-up to the Centennial of the war, which was surrounded by great hoopla. In those days it was perfectly respectable to honor the Confederates who served, which is why the songs of both sides were featured in equal numbers and with equal prominence.

It was even OK to be a Confederate sympathizer. Nowadays, I assume you would be expelled from school for such sentiments. At the very least.

In those days I was living in suburban Maryland, and I can tell you from personal experience that there were plenty of people who were sympathetic with the Rebels. The Confederate soldiers had won so many astounding victories against seemingly insurmountable odds — how could one not admire them?

And sympathy for the Confederacy in Maryland went all the way back to the Civil War, handed down from father to son just like memories are passed down here in the Old Dominion. I went to school with some collateral relatives of General Jubal Early, whose ancestors had lived across the Potomac from their more illustrious cousin. Their family relationship helped cement their sympathies, and they were hardly the only ones, but a blood relationship was not a prerequisite for such sympathies.

There’s something about the Confederate cause that strikes a chord in the hearts of people who cherish resistance to tyranny.

Deo Vindice.

Heart-warming story, Sir. Many thanks.

To this reader, a significant fact that is so obvious that it’s hidden–that “Brigade of Old Men and Young Boys” who repelled a fighting force five times their number–needs must have had superb marksmanship skills.

Think of it: youngsters and old gray-beards–all deadly with a rifle. The past is truly never dead. Their deeds liveth for evermore.

Let us honor their courage and fortitude by promoting and practicing riflery today.

It is hard to sum up my feelings as a teenager about the civil war, as the Baron is aware, in UK it was considered a war about slavery, and “Uncle Tom’s Cabin”.

I did not find out that it was not quite so simple until much later when I read Johnson’sd “History of the USA”. Paul Johnson is that rare beast, an alt-right historian.

His was the first text I read that toppled Lincoln from his pedestal of pseudo-godship.

I still suspect that the abolition act, following hard on the heels of the dreadful losses at Antietam was a cynical political ploy to bury bad news.

Lincoln had drafted the emancipation proclamation long before Antietam, and waited only to avoid it looking like desperation.

Trying to shoehorn conspiracy into Lincoln’s actions is to demand less-believable ideas to take precedence over more realistic ones.

It was an entirely pragmatic political decision to shift the justification away from Saving the Union to Ending Slavery for three political purposes:

1) After Lee had driven McClellan back from Richmond it had become obvious the war was going to be long and bloody and sooner or later Northerners might start rethinking cost vs return, not to mention whom said return benefited.

2) The pressure on the British government to grant the Confederacy belligerent status, thereby making it legal, and probable, that the Royal Navy would break the Northern blockade of Southern ports, was nearing a critical level and, since the British could give a fig whether the Union was saved, some casus belli the British would find acceptable had to be presented to stave off such a move. We’ve seen something similar in this century when the War on Terror morphed, as a political calculation, into Nation Building, ostensibly intended to force Jeffersonian Democracy on people who could not culturally understand it and possessed no desire whatsoever to acquire it.

3) And last but not least there was some hope that, if it became widely known, it might instigate slave uprisings within the Confederacy, but not within “loyal” slave states which were specifically excluded, thereby creating a Fifth Column.

Lincoln, whose chief contribution to American political science concerned whom to fool and when to fool them, required something that could at least be spun as a victory in order for the Emancipation Proclamation, Executive Order in modern terms, to not be laughed out of court, as the expression goes. Sharpsburg, as tenuous a victory as it was, provided that opportunity. If politicians are aware of anything it is political timing. Lincoln was wise not to wait for coming up was Fredericksburg (Northern loss), followed by Chancellorsville (Northern embarrassment), and Vicksburg (which for the first four months of ’63 had all the markings of a quagmire). Without the Emancipation Proclamation, which was entirely for domestic and international consumption for it effected the Confederacy not at all, issued when it was both Britain and France almost certainly would have entered the war on the Confederacy’s side.

In the first sentence you validate MC’s claim that the EP was a political calculation and in the next attempt to say that it is somehow a conspiracy theory to recognize it as a political calculation, which you agree that it was. MC was not wrong in his assessment.

1) correct, and because the average unionist was naïve enough to think the war could be ended without slavery. Many Union soldiers, especially from the Midwest, had a change of heart when they saw slavery firsthand and how integral it was to secession. Take away slavery, and the secessionist arch collapses.

2) that’s normal diplomacy. The shortsighted leftists running the revolution assumed they would win and therefore made no preparations for diplomatic work. Everything was improvised, a day late, and a dollar short. A stark contrast from the American revolution, which sought diplomatic support from France and other European nations from square 1.

3) starting slave revolts was never an option. The paranoid confederacy feared hyphen, but it was easier and safer to merely let slaves flee to Union lines, draining the Confederacy‘s labor pool and forcing them to increase their internal policing.

In short, normal politics are not “conspiracy,” they are standard fare. Only the Confederacy demanded perfect results from being both stupid and energetic.

The Emancipation Proclamation was a legal farce. Lincoln promoted it as a “war measure”, not a law.

Lincoln could not enact a law as presidents do today. Congress would have had to make it law.

The CSA considered itself to be a foreign country. The president or the government of one country can’t impose a law on another country. It all hinges on whether or not secession was legal and forcing people at gunpoint to live in your “union” proves nothing.

The EP excluded slaves in northern states (There were slaves up north, both runaways and legally held) and in areas occupied by the US army and navy.

The EP says slaves were “freed” in areas “under arms and in rebellion” against the federal government. So, IF the war was all about slavery as we are constantly told, all the racist southerners would have had to do was throw down their guns and go home singing “My Country Tis of Thee”.

The abolitionists complained that Lincoln didn’t go far enough. William Garrett called Lincoln “a first-rate second-rate man”.

General Sherman didn’t want to fight “for the N**GERS” and threatened to resign. General Grant pleaded with him not to.

People in the north feared that the EP would encourage “the D**KIES” to come into their states. Lincoln told their representatives in congress that they didn’t have to accept them.

The Italian hero, Garibaldi was offered a commission as a general in the US army, leading a battalion of Italian immigrants. He asked the diplomats if it were true that the war was being fought to end slavery in the United States and was told it was to establish the authority of the federal government. Garibaldi said he wanted nothing to do with such a cause.

For the first two years, everybody in the north denied that the war was being fought to end slavery, even Lincoln.

God, I could keep on like this about the “American civil war” for another hour. Even the name is inaccurate.

Typical revolutionary myopia.

The notion that the emancipation proclamation was a farce is [an assertion that I deprecate]. As commander-in-chief, Lincoln had every right to dictate policy to regions under military governance, of which occupied enemy territory is the poster child. His proclamation achieved de facto emancipation, which would be harder to undo after the war, showing genuine foresight.

Yes, the emancipation proclamation was a wartime measure, and nobody apart from historical illiterates and lost causers (but I repeat myself) pretends otherwise. Permanent abolition was achieved with the 13-15th amendments, and there is no shame in admitting it wasn’t accomplished with one stroke of a pen. Liberty requires hard work.

Yes, slavery would have been protected in the early years if they stopped fighting. Lincoln, as a moderate, didn’t demand instant abolition and was willing to let it die peacefully in its sleep as the inefficient, unproductive institution strangled itself (this hinged upon preventing its spread, like containment of communism). The slavers knew this, which is why they chose the instant results of sudden death over peaceful/gradual abolition.

Yes, many northerners and Midwesterns had similar racial views of blacks, and began the war indifferent to slavery/abolition. This indifference is when the unionists were at their weakest and most vulnerable. As the war dragged on, many of them changed their minds about the matter, and even those who still hated blacks preferred to make them homesteaders instead of sharecroppers (which combines the disadvantages of both peasant culture and capitalism with none of the advantages).

You seriously think Garibaldi refused to fight because “it was to establish the authority of the federal government”? The real Garibaldi wanted to fight in 1861 with 2 conditions: 1) he wanted to be commander-in-chief, which was politically impossible, and 2) he wanted the power to immediately abolish slavery wherever he found it. Like the confederate revolutionaries, Garibaldi wanted instant results, but Lincoln was playing the long game. If the war was short, then slavery would self-destruct. If the war was long, he’d acquire the necessary political clout to promote abolition without looking desperate and/or arbitrarily exceeding his lawful authority. Garibaldi‘a endorsement of abolition at such an early stage would also popularize the concept to a European Audience, helping diplomatically isolate the Confederacy. Win-win-win.

When Lincoln eventually did make the proclamation, Garibaldi was busy campaigning, but sent Lincoln a letter praising him and supporting his decision.

Yes, “civil war” is a bad name, the older name “the war of the rebellion” is much better. It was not a war between states, and the Union veterans hated that name.

“…occupied enemy territory…”

Are you saying that the Confederacy was a foreign country? You assertion only works if it were.

It has never been established if secession was legal or not. NEVER. The result of the war means nothing because “trial by combat” is NOT part of American juris prudence. We disagree, correct? Suppose I were to take out a shotgun and blow both your legs off, would you then say I was right, and you were wrong?

Utter non-sense. Not to mention, an insult to a free country.

Naturally, you will bring up Fort Sumter, but that proves my point.

Forts Sumter and Pickens were occupied by US solders against the will of the Confederate state and federal governments. They were asked to leave. They were told that the occupation was an aggressive act. President Davis sent THREE DIPLOMATS to negotiate the occupation and Lincoln not only refused to see them, but he also forbade anyone else from seeing them. Lincoln and his Secretary of War secretly worked with the US navy to re-enforce the forts, which can be interpreted as an act of war. Yes, the US federal government can make war on a state while it’s in the union. SEE: The Tariff of Abominations and the Nullification crisis of 1832–1833.

Truth is, Lincoln not only did NOT “do everything to avoid war” as we are told, he did a lot to provoke it! The news of the approaching fleet forced the militia to fire on Sumter.

Don’t bother saying “But they were protecting federal property!” unless you want to explain why British solders are not currently occupying camps and forts in the United States that they had built in the first half of the 18th century.

Regions in rebellion count as “occupied enemy territory,” whether they are independent or not. This is laws of war 101, and trying to pretend otherwise is leftist subversion 101.

Trial by combat is a red herring; Lincoln did not demand it, the Confederacy embraced it because they were too impulsive and short-sighted. Patient diplomatic heads were rare in the Deep South. And once they fired the first shot, they threw away every other less-violent option. Demanding the right to start wars and still be treated with kid gloves is classic leftism.

Fort Sumter is as “aggressive” as the Maginot Line. Forts are defensive, not offensive. Nor is refusing to surrender “aggression.” Lincoln did indeed refuse to see representatives because his government did not diplomatically recognize the Confederacy. And no nation is obligated to make unilateral concessions to governments they don’t recognize. Without diplomatic recognition, the Confederacy had no claims to those forts that could be stronger than the Federal government (especially when we consider it was federal, not state, property) and the state stealing federal property and starting revolutions if their demands for loot aren’t met is a bad precedent.

The reason British troops don’t occupy American forts today is because they do not own them de jure. Property ownership matters (although not to leftist revolutionaries) and so Britain has as much claim to fort Ticonderoga as the Confederacy (I.e., zero).

In short, the federal government has rights that no state can trample upon, and sending to supplies to its own forts is not “aggression,” no matter what the leftist revolutionaries think. Lincoln was a moderate, but he at least wasn’t a RINO pandering to oathbreakers and backstabbers.

“I remember standing one day looking at a monument in Athens, Ga., when a young collegian said to me, ‘I suppose you object to this monument being here.’ ‘Oh no,’ I said, ‘if you people want to perpetuate your shame, I care little about it. You are simply telling the story to your children of how you tried to pull down the old flag and how you failed.’ Another day I stood by the monument in Winchester, Va., and read upon it an inscription which told how men had died for liberty, had died for constitution in that country. An old gentleman asked me what I thought of it. ‘Oh,’ I said, ‘the day will come when you will put up a ladder against that monument, and you will hire a colored man who once wore the shackles to climb that ladder and efface every word of that inscription, for it is false. There is no truth in it.’ Those were brave men, and I am willing to pay tribute to their bravery; but they did not die for liberty, they did not die for their constitution, they did not die for their country.”

-Colonel Elisha Rhodes, GAR, to an audience of Union soldier veterans in Boston, 1910

Source: https://angrystaffofficer.com/2021/06/20/we-believe-in-making-treason-odious-u-s-veterans-of-the-civil-war-attack-the-lost-cause/

They did die for their country; the Confederacy was their country. They didn’t die to pull down the old flag, either; they had their own to honor.

Gloat while you can. We will win in the end. If we don’t, at least we have the sentiment expressed in “A Pict Song”:

“…while you, you will die of the shame

And then we will dance on your graves”

So you admit that their oaths of loyalty were lies?

It’s amusing to see fake right wingers brag and boast about how their daddies broke their oaths and lied repeatedly, yet think those who commit the crime of noticing are somehow the bad guys.

Then you must laugh heartily at accounts of the those who fought for independence in the American Revolution. Were they not British subjects who owed their loyalty to the Crown and His Majesty’s representatives?

Were the men and women who fought The War of Unification traitors to the Italian states where they lived by establishing the Kingdom of Italy?

Yes, as a matter of fact, they were subjects who owed loyalty. The game-changer was diplomatic recognition by France; before this, the Declaration of Independence was only words on paper. Diplomatic recognition is everything when it comes to forming nations and setting boundaries, and the Founding Fathers were much smarter than the Confederacy because they sought diplomatic recognition as an imperative, rather than an afterthought. The confederates thought that king cotton would give the Europeans no choice, but even before the war king cotton’s value was declining compared to other agricultural products (especially hay and fodder). A southerner wrote a book in 1857 to warn that this was impending, but the book was banned/censored, and lynch mobs murdered 3 people caught possessing it- hardly comparable to the Founding Fathers’ commitment to free speech!

Without diplomatic recognition, the Confederacy had less legal standing than the Indian tribes. This is a bitter pill to swallow, but one that is ignored at one’s own peril.

Michael Gladius

I’m replying to your November 2, 2022 at 7:10 am post.

The indian tribes were NOT recognized as independent countries by any government and had no diplomatic missions anywhere. They were for the most part, nomadic and had no place they could call a “country”. The Confederacy had borders, land, governments, military, industry, coinage, and diplomats; in short, everything you could say makes a country.

But let’s say you’re right about the American indian tribes being countries.

GOOD! You just recognized the CSA as a country separate from the United States.

Why? Because the CSA was allied with and recognized by the Five Civilized Tribes of Oklahoma.

They were more faithful and exegetical to the Constitution than Colonel Elisha Hunt Rhodes ever was.

Take some time and read the Ordinance of Nullification of 1832 and see a staunch defense of the Constitution.

Additionally, in 1798 the Federalist Party controlled Congress passed the Alien and Sedition Act which criminalized published criticism of the president, John Adams, and Congress. This was passed less than a decade after the Bill of Rights was ratified (1791) and contained, “Congress SHALL MAKE NO LAW respecting an establishment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof, or abridging the freedom of speech or of the press …” In a little more than eight years and the Federalist Party, centered in New England and the North, began passing laws violating the Constitution. The Federalist Party died out after the War of 1812 but that Big-Government mindset never did and still exists.

Nullification is only valid in defense of the Constitution. Nullification as a means of repudiating the Constitution tips the rug out from under its own feet. All previous crises knew that; the collectivists were the first to break ranks.

Really? Which unconstitutional laws did the federalists pass that remained on the books until 1860? The Fugitive Slave Act wasn’t their doing, but it gladly trampled on free states’ rights.

Yankees still gotta Yankee. My grandparents, whose parents lived through the war and Reconstruction, would would just shrug and say, “What do you expect?”

I didn’t realize Kansans counted as “Yankees.” Or do you also consider the 180,000 white southerners from the hill country who fought for the Union to be “Yankees” and “immigrant mercenaries”?

My ancestors settled in Kansas as free men. They got into gunfights with slave owners and slave lobbyists before the war, who invaded our state and forced a pro slavery government upon us at Gun point. Then my ancestors fought for the Union against pro slavery guerrillas after the rebels’ western army blundered its way into destruction at Pea Ridge. Then, after the war, my ancestors still got into gunfights with the Ku Klux Klan because they committed the unforgivable crime of being Irish and Catholic.

One doesn’t have to be a Yankee to think that liars, cheats, and oath breakers are beneath contempt.

in the early 1870s congress investigated the “reconstruction” and found that the klan was formed BECAUSE of the military occupation, not the other way around.

Had the south gained independence, there would not have been a “reconstruction”, no klan, no resentment against the slaves and freemen. Thus, race relations in the south would have been better than that which we know.

PS: The US army had segregated units in the Korean war, the Confederate army had indians and “knee-grows” mixed in with the Irish and Jews.

PSS: The eugenics movement was started in the north and inspired the NAZIs.

The Klan was formed in Tennessee as a way to resist giving freedmen the right to vote, and was eventually smashed in 1872 (it was revived in 1915). It was formed at a time when the army was gutted and being transferred west, so to blame the army for its creation is putting the cart before the horse.

The notion that the south’s independence would have resulted in harmonious race relations is a lie. Before the war, freedmen were held in contempt, poor white non-slave owners were considered white trash, and a virtual police state of paranoia about slave rebellions was everywhere. At the time, the slave lobbyists had no qualms about saying this, but after emancipation and the lack of slave revolts (instead the slavers being more violent, like Antifa with half the IQs) did they started claiming otherwise.

Yes, the army did have segregated units in Korea, and the last one was disbanded in 1954. Name one of these “mixed” confederate units that wasn’t upper-class men with accompanying slaves.

The eugenicists had a lot of support from Woodrow Wilson, a progressive who helped establish the lost cause mythos, and the keystone connecting the Confederacy with modern Marxism. When Mexican Bolsheviks started the Christero war in the 1920s, guess who collected donations for the Bolsheviks?

Here’s an oddity; Amazon UK have the vinyl LP of “Songs of the North and South” listed as an import for just 6.99 pounds (my keyboard doesn’t do pound signs!). I’d have thought it would have some rarity value, but maybe it sold well in its day.

That seems like a really good price. My father probably paid $2.00 for ours when it was new. After sixty years of rampant inflation, that would be approximately $18.00 now.

I have my family’s copy of “Song of the Civil War” featuring the Smith Brothers, a Centennial Issue. Played it a lot in my youth. Now day’s I listen often to the 2nd South Carolina String Band.

In the end, the most you can do to a man, is kill him. You cannot kill an idea, but you can oppose it with another idea. I am a descendent of a Confederate veteran, and glad to make the claim. I served honorably in the Yankee Army, until I got hurt, whereupon I found out what Yankee Honor really consisted of. If you can hang a dollar sign on anything, you could have one on a current American flag, and few would notice the difference, and most would salute it. I’m not bitter about anything, I’m glad for the opportunity to learn how things really work, and are, and that knowledge is more valuable to me than most things I know. Deo Vindice.

I admire the South but I cannot understand the strategy of the South.

Gettysburg, where a battle was fought, was NORTH of Washington!

The South bypassed the capitol of its mortal enemy and they didnt even destroy the factories of the North.

The South reminds me of Hannibal who fought against Rome.

Yes, he destroyed one roman army after the other, but Rome and its ability to raise new armies and weapons making capability were never attacked.

The same with the South. Lee won many battles but he never went for the jugular of the enemy.

Thats why he lost.

The Potomac River provided to much defensive strength on the west and southern side. The best direction for assault was from the north and that meant somehow getting around/behind the Army of the Potomac. But Lee understood that even bagging Washington would not end the war. The South’s only real hope was intervention by allies, much like what saved the Continental Army during the first Revolutionary War. Showing the ability move at will in Northern territory might persuade some that the South could hold its own while demonstrating that the North did not enjoy the complete martial dominance that was assumed.

Lee’s primary intentions were much the same the summer of ’63 as the preceding summer of ’62, which led, by unfortunate carelessness for the Army of Northern Virginia and sheer luck for the Yankees, to Sharpsburg. An attempt to provide provender for his army and some relief for the logistics of the South. The battle at Gettysburg was as much a surprise to Lee, due to the misunderstanding/disregard of instruction by Stuart, as Sharpsburg had been the preceding year. The Confederate Armies, in all theaters, were literally on starvation rations from First Manassas to Appomattox. They almost never enjoyed the luxury of what a Northern soldier would consider to be regular rations. The idea was to sweep up into the rich agricultural farmland of Pennsylvania and gather as much provender as possible and then, if the opportunity presented itself, advance on Washington from the north. This was not the theft and rapine practiced by Grant and Sherman’s troops. This was, by directive, to be orderly and in accordance with the rules of war. Lee personally ordered a Confederate soldier summarily shot for stealing a pig from a Pennsylvania farm. Yankees, because they were dealing with “insurrectionists” (and well fed), suffered under no such compunction.

Not to put too fine a point on it, Lee was, by intention, leading a disciplined Army, not merely organized brigandage. Lincoln’s specifically promoted Grant, Sherman, and Sheridan on the understanding that they had no such scruples.

That’s as convincing as saying Rommel never committed war crimes in North Africa or the Russian front. Lee absolutely enabled Looting by confederate cavalry, and it was no different from how the Union conducted itself.

The main reason confederate looting was less widespread was because they kept losing battles in the west and had no capacity to do more than partisan raids. The notion that they were somehow “too honorable” is a lie invented by bitter losers.

As a matter of fact, Rommel did not commit any so called war crimes, there is only war and there are only Victors and vanquished in the end, the means is only semantics.

So being part of massacring civilians for the crime of being “subhuman” isn’t a war crime? Participation and/or calling the shots absolutely qualify.

Such philosophy that states “there are no war crimes” is highly amusing when it comes from confederate apologists who wail “woe is me, the Yankees burned down southern farms!” The leftist truly does cry out loudest when he is attacking someone else.

The south had no strategy, much less a unified one. They improvised everything and compensated for their lack of planning and staff work by hyper aggressive tactics reminiscent of Japan between 1937-1943.

Lee’s victories came at a high price; in the first 27 months of the war, the Confederacy lost more men than any single army ever fielded. Lee bears much responsibility for this, as he chose aggressive tactics that were costly in the hope of quick victories.

Elsewhere in the Confederacy, other commanders blundered their way from defeat to defeat. Lee created a stalemate Plato on easy mode; in the west, even the Union’s mediocre generals could reliably beat the Confederacy.

Thank you for this essay. I have an ancestor who died at the Battle of the Crater on July 30th 1864. He was a corporal in the 22nd SC Infantry. I do not know if he died in the mine explosion or in the savage fighting afterwards. I am not and will not give up the fight defending history to those who only destroy.

My great-great-granduncle David Weisiger led the charge at the Crater. There’s a plaque with a verse about him on the wall inside the chapel at the cemetery in Petersburg where he is buried.

One of the later installments in this series will be about the Crater.

TO: Michael Gladius who has cut off replies to his posts.

Why didn’t Lincoln prove his assertion that secession was illegal instead of preparing for war? Everything rests on that and NO ONE has ever proven secession illegal in 1860 and 1861. The best people can do is to bring up rulings AFTER the war. I want to know if “the crime” was illegal at the time it was committed. The United States Constitution forbids punishment ex-post facto.

I didn’t cut off replies, the website ran out of space.

As to your question, Lincoln did do much to dispute the legality of secession. He refused to recognize the Confederacy, its government, or its ambassadors. He only negotiated with individual state governments, and managed to keep the 4 border slave states from seceding. He also poured a lot of effort into ensuring no other nation recognized the Confederacy. But all the diplomacy in the world didn’t stop the Confederacy from starting the war. At which point, only force could decide the issue- any Supreme Court ruling would simply be ignored by the Confederates.

The notion that Lincoln prepared for war instead of proving secession was illegal is also pretty flimsy. Resupplying existing forts with rations (he specifically instructed that no arms were to be sent) is not the same as building new forts or calling for volunteers, both of which happened after the war started, not before.

In short, Lincoln relied primarily upon diplomacy to argue that secession was unconstitutional, and the Confederates started a war before it could be filed with the Supreme Court. Once the rebels began shooting, lawyers took a back seat to winning the war. Had the confederacy been less impulsive, they might have gotten their day in court. But they didn’t care enough to dot their “i”s and cross their “t”s. They believed in their own racial superiority and king cotton. They eschewed de jure solutions for de facto ones, and then lost in both fields.