This is the third essay in an occasional series. Previously: Part 1, Part 2.

Requiem for a Culture

Part 3: The Battle of Staunton River Bridge

The past is never dead. It’s not even past.

— William Faulkner, Requiem for a Nun, Act I, Scene III (page 80 in the Vintage paperback edition)

The Roanoke River is a modest river at the bottom of a deep gorge where it flows out of Roanoke to the southeast. By the time it empties into Swan Bay and Albemarle Sound in coastal North Carolina, it is a broad expanse of slowly-moving water.

For a portion of its passage through Virginia, the Roanoke River inexplicably assumes a different name. According to Google Maps, it becomes the Staunton River where Cheese Creek joins the flow just below Altavista in Campbell County. It then resumes its former name where it widens out as it becomes the John H. Kerr Reservoir, a.k.a. Buggs Island Lake, between Charlotte and Halifax Counties. In reality, however, the two toponyms are not that clearly delineated — which name is used depends largely on local customs.

To make matters even more interesting, the name of the river, like that of the city of Staunton (which is nowhere near the river), is pronounced “Stanton” — one of many regional peculiarities of Virginia pronunciation.

In the middle of its term as the Staunton River, it is crossed by a railroad bridge that was strategically important to the Confederacy in the summer of 1864. At that time General Robert E. Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia were entrenched in and around Petersburg, where they were besieged by the Union Army commanded by General Ulysses S. Grant. The Confederates’ main supply route was a single railroad line that crossed the Staunton River from Charlotte County into Halifax County just south of Roanoke Station, nowadays called Randolph.

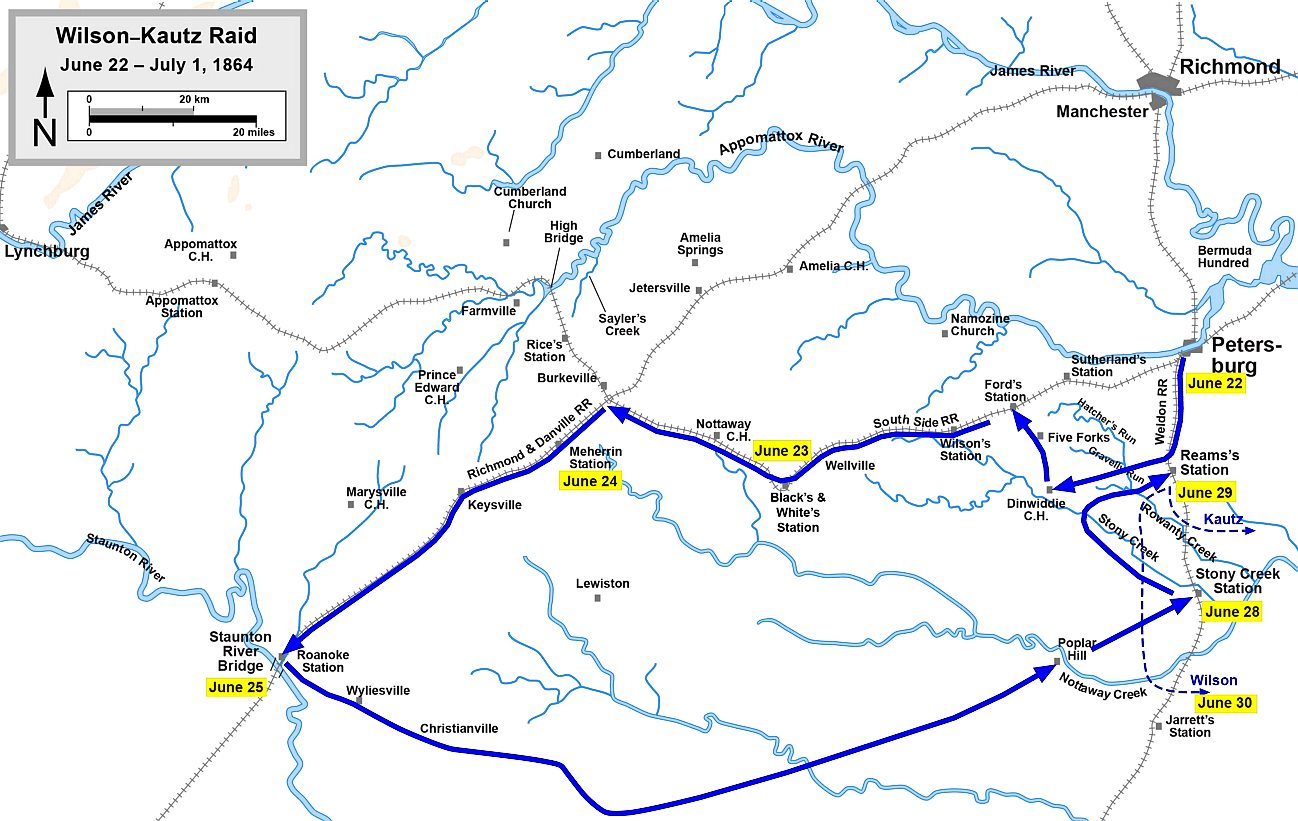

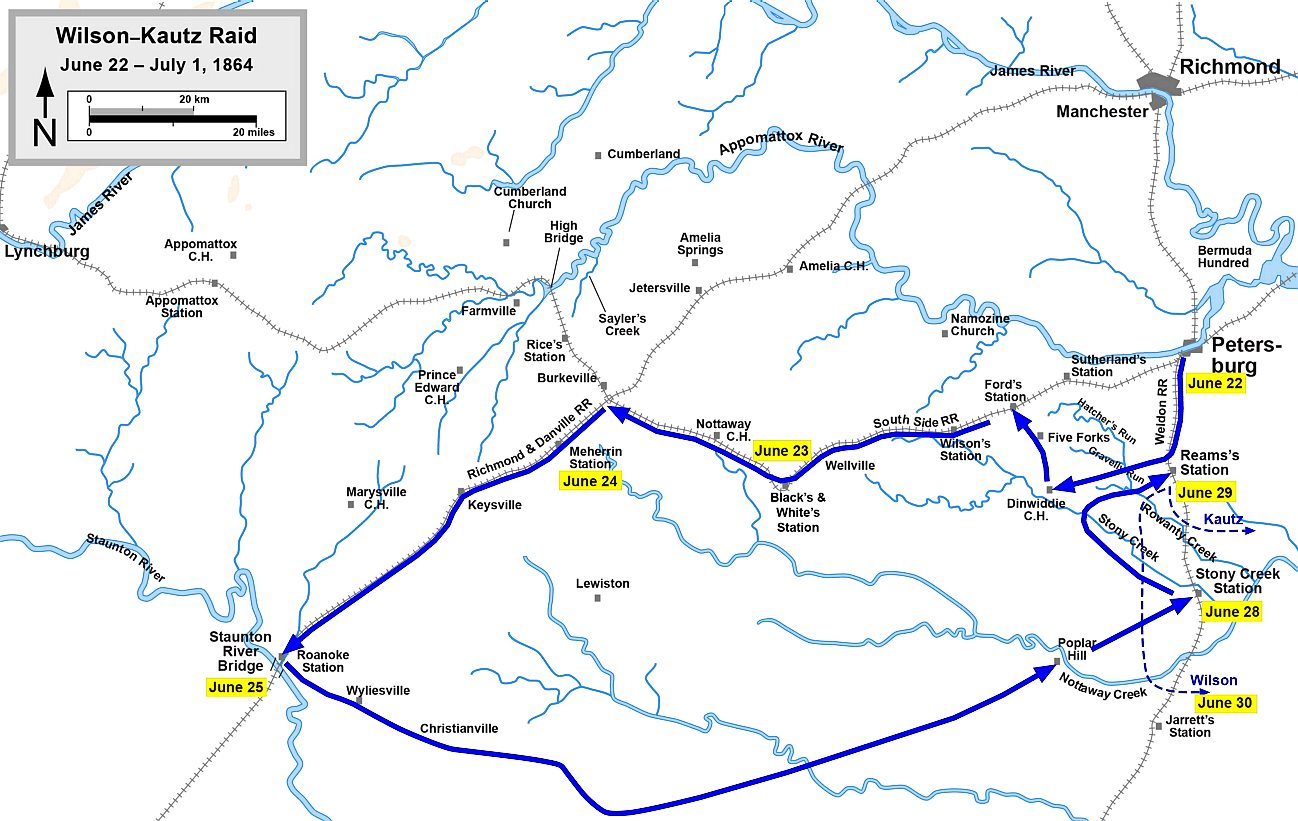

In late June General Grant ordered a raid on the railroad line. 5,000 cavalry troops led by Brigadier Generals James H. Wilson and August V. Kautz left the Petersburg area on June 22nd and proceeded west and south along the railroad, tearing up track and burning down stations. Their ultimate objective was to destroy the Staunton River Bridge.

Below is a map of the raid. It’s somewhat inaccurate in its details — for example, it puts Cumberland significantly to the south and west of its actual location. It also misspells “Nottoway”. Nevertheless, it’s a useful overall schematic diagram of events during the raid.

(Click to enlarge)

(Click to enlarge)On June 23rd General Lee sent word to Captain Benjamin Farinholt, who commanded a battalion of reserves charged with defending the bridge, warning him that the Federals were about to come down hard on him, and ordering him to prevent the bridge from being destroyed. If the Union troops were able to get to the bridge even briefly, they would pour oil on its wooden structure and torch it.

Captain Farinholt’s situation was dire. He commanded a force of fewer than 300 soldiers, and had only six artillery pieces with which to confront the sixteen being fielded by the Northern cavalry.

That night he sent word out to the surrounding communities, asking for volunteers to help defend the bridge. Military-age men had already been siphoned off by conscription, so the captain was drawing on teenage boys and men over 45 to form hastily-assembled militias. In popular accounts written after the war they were referred to as the “Brigade of Old Men and Young Boys”.

The new arrivals were also augmented by 150 Confederate regulars from detachments stationed around the region. With the regulars added to the old men and boys, Captain Farinholt was able to deploy a force of 938 men — less than 20% of the size of the cavalry units bearing down on him.

The battle was joined on the afternoon of June 25th. As happened so many times during the Civil War, the South prevailed against a much larger Northern force. 42 Union soldiers (including several officers) were killed, 44 were wounded, and 30 were missing or captured, while Captain Farinholt’s men suffered 10 killed and 24 wounded.

The details of the battle make for inspiring reading. The excerpts below are from the Staunton River Battlefield website:

In June of 1864, Confederate General Robert E. Lee and his Army of Northern Virginia were engaged in a desperate defense of the city of Petersburg, Virginia. Victory for Lee depended upon a steady flow of supplies from the west and south, via the South Side and Richmond & Danville railroads. Union General Ulysses S. Grant knew that if these supply lines could be destroyed, Lee would have to abandon Petersburg. To accomplish this, Grant planned a cavalry raid to tear up the tracks of both lines and destroy the Richmond & Danville railroad bridge over the Staunton River.

The raid began on June 22, and was led by Brigadier General James H. Wilson and Brigadier General August V. Kautz. They left Petersburg with over 5,000 cavalry troops and 16 pieces of artillery. As they moved west, the Union raiders were closely pursued by Confederate General W. H. F. “Rooney” Lee and his cavalry. Although Lee’s troopers occasionally skirmished with the invaders, they were unable to stop their advance. During the first three days of their raid, Wilson’s cavalry tore up 60 miles of track and burned two trains and several railroad stations.

Just south of Roanoke Station (present-day Randolph) was a long, covered railroad bridge over the Staunton River, Wilson’s final objective. The bridge was defended by a battalion of 296 Confederate reserves under the leadership of Captain Benjamin Farinholt. On June 23rd, at 10 p.m., Captain Farinholt received word from General Robert E. Lee that a large detachment of enemy cavalry was moving in his direction to destroy the bridge and that he should “make every possible preparation immediately.”

Captain Benjamin Farinholt: “By the trains at 12 o’clock that night, on the 23rd, I sent off orderlies with circulars, urging the citizens of Halifax, Charlotte, and Mecklenburg to assemble for the defense of the bridge, and ordering all local companies to report immediately… On Saturday morning, the 25th, about 10 o’clock I had received, citizens and soldiers inclusive, 642 re-enforcement. Of these about 150 were regulars, organized from different commands, my whole command numbered 938 men.”

Continue reading →

Russia launched a new series of cruise missile attacks on Ukrainian cities, including the capital Kyiv, targeting energy plants and other critical infrastructure. Most residents of Kyiv have lost water service, according to the latest reports.

Russia launched a new series of cruise missile attacks on Ukrainian cities, including the capital Kyiv, targeting energy plants and other critical infrastructure. Most residents of Kyiv have lost water service, according to the latest reports.