Some of the things that President Biden and the Democrat Party have been doing over the past few months are pretty bizarre, considering that this is an election year.

Hispanics and even blacks are shifting away from the Democrats. Young people — the parti-colored Zoomer TikTok generation — are increasingly drawn towards Donald Trump. The way things are going, there won’t be enough dump trucks available to haul in the “found” ballots required to put Joe Biden over the top on the night of November 5th. The Democrats are virtuosos at rigging elections, but even in the dystopian twilight of 21st-century America, elections can only be stolen at the margin. The race has to be at least somewhat close in order to pull off an effective steal.

The Democrat apparat seems utterly unconcerned with making sure the race is a tight one. One unpopular policy after another is being pushed — open borders, criminals released without bail, the promotion of sexual perversion, the war against the internal combustion engine, uniformed soldiers with pink hair mincing around in high heels…

And, to top it all off, there was the “Transgender Day of Visibility” on Easter Sunday. Don’t they even want to win the election?

Well, maybe they really don’t.

I’d been thinking along those lines for a while, and then last week I happened to read something similar at ZeroHedge, an essay saying that they’re going to let Trump win.

These are the key paragraphs:

Let Trump back in, and fight him on home turf — in the maze of the executive bureaucracy. Some of his backers have announced their intention to become politically competent in the event that he wins — but compared to the alternatives, that’s a very manageable risk.

More importantly: let Trump hold the bag for the all-but-guaranteed economic calamity of the next four years. The regime could skate for another decade if they succeed in pinning the collapse on a dangerous, erratic right-wing upstart. [emphasis added]

Everything I say here tonight is pure speculation. I’m not an expert on any of these matters, and especially not on financial issues. I’m just a reasonably well-informed layperson who reads a lot of information from diverse points of view.

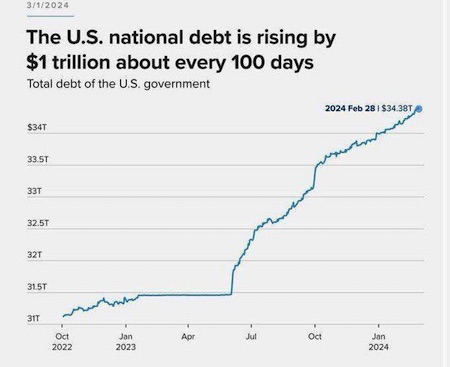

It’s undeniable that the country is headed towards some form of fiscal calamity. As I mentioned last month, money-printing is being taken to new extremes:

I swore off making specific predictions after the previous great fiscal crisis in 2009, when my prognostications were so completely wrong. I never would have thought they could keep the racket going for another fifteen years, but here we are. The Powers That Be have managed to do a lot with derivatives and real estate bubbles.

But the debt graph can’t keep going up with a steadily increasing slope — it just can’t. Someday the pyramid scheme will come crashing down, and the chickens will come home to roost. Based on the current debt acceleration, it won’t be much longer. It might take a week; it might take a decade. But the chickens will be roosting relatively soon.

The thing is, the people who keep the Ponzi scheme afloat know exactly what’s coming. They know the money-printing tactic will eventually stop working. It’s a complex process, what with cryptocurrencies, CBDCs, derivatives, paper and digital “futures” of precious metals, and now the BRICS alternatives. Keeping those plates spinning must surely be a tricky business.

And the people in charge know that a collapse of the dollar will eventually come. In order enrich themselves fully, and assure themselves an unbroken hold on the levers of power, they will need to time the crisis carefully. At exactly the right moment they will topple the pillars supporting the dollar-based economy, after having thoroughly prepared the replacement system that will be built on the smoking ruins of the old one.

So which patsy will be nominally in charge when the house of cards comes tumbling down? Who will preside over the Great Collapse?

Whose face will be on the Zimbabwe-style trillion-dollar bill?

For a long time I thought Brandon was being set up as the fall guy. He was always obviously a disposable president, a non-re-electable senile geezer who could be pushed aside when he was no longer needed. The people who crafted his policies and wrote his speeches clearly didn’t try to make him more popular. I assumed that when the time was right, he would be gently eased out (and Kamala, too, although that part would be tricky), and a substitute such as Gavin Newsom or Big Mike installed to run in 2024, someone who was at least plausible enough that the election could be rigged on his behalf.

But it never happened. And the scripts that Brandon has been following have been so damaging to him that it’s obvious that his handlers don’t really want him to win re-election. It is intended that he go down in flames, taking the Democrat Party with him.