After a long hiatus, Max Denken returns with a film review that is much more than a review: he has a family connection with the area of Poland that abuts the border with Belarus and is featured in the movie.

Brown Border

by Max Denken

The movie

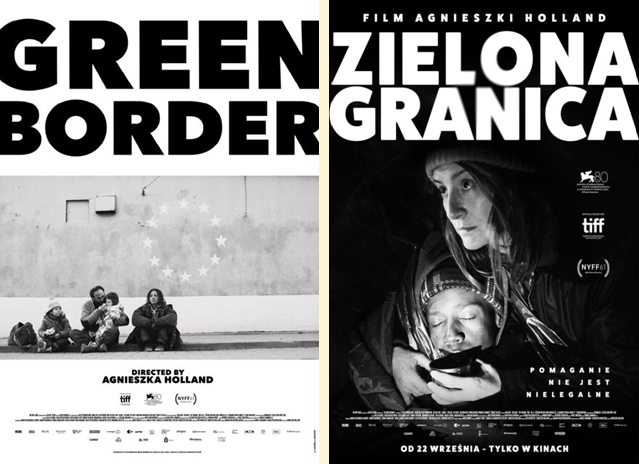

Tired and jet-lagged upon arrival in Warsaw, I bide the daytime hours. A walking distance from my hotel, a movie theater is playing Green Border, the new film by Polish émigré film director Agnieszka Holland.

America’s most prominent film school and a stab at a Hollywood career are as long behind me as are Holland’s days at the FAMU film school in Prague. I once introduced to a Los Angeles audience Krzysztof Zanussi, the Polish film director with whom, as his assistant director, Holland began her career, but my paths never crossed hers nor did my interests in film or life run parallel. Still, I loved her children’s film The Secret Garden (1993) and, as an animal lover, could identify with her revulsion at a driven hunt’s wholesale slaughter of wildlife in Spoor (2017). I drag myself out of the hotel and go to see Green Border, Holland’s film that had just had its premiere screening at the 80th Venice Film Festival in September, 2023.

What I proceed to endure for two and a half interminable hours is an agitprop salad similar in intent but far below the artistic level of such famous purveyors of film propaganda as Sergei Eisenstein for the Bolsheviks and Leni Riefenstahl for Hitler. There is no story with real human characters in the traditional narrative sense but a weepy outburst about numinous Syrian, Afghan, and African refugees trying to invade Poland’s via its border from Belarus and being brutally repulsed.

The New York Film Festival synopsized the film as, “A Syrian family leaves the violence of their country behind, hoping to cross from Belarus into Poland and then onto the safe haven of Sweden. But, like so many lost souls, they end up caught in a political maelstrom, demonized by the Polish government and press and used as pawns in an inhumane, deadly border game.”

The reality background to Holland’s invention is that in July, 2021, Alexandr Lukashenko, the dictator leader of Belarus, threatened to “flood” the European Union with drugs and migrants and proceeded with this scheme of hybrid warfare. Belarussian agencies in tandem with some Middle Eastern airlines fraudulently promoted easy entry into the EU’s territory and arranged for the delivery of migrants to the Polish-Belarus border. It was an inhumane, cynical ploy probably ordered by Lukashenko’s ally in the Kremlin to either force a stream of undesirables onto Russia’s foe, Poland, or to make Poland look bad if it refused to grant them passage.

A flood of Iraqis, Syrians, Afghans, Congolese, Cameroonians, and Sudanese followed to the forested border. By November 2021, Poland’s border guard had intercepted over 32,000 migrants’ attempts to invade Poland. Having defied the EU’s order to take in a share of Angela Merkel’s invitees since 2015, Poland’s PiS government, to its credit, was not going to yield to this Putin/Lukashenko ploy, either.

And that evidently unleashed in Ms. Holland — daughter of a Polish-Jewish high communist official and notorious European “progressive” — her own flood: that of the maternal bonding female hormone oxytocin. The same one that a group of German — what else — scientists stated in their 2017 paper “Oxytocin-enforced norm compliance reduces xenophobic outgroup rejection “ would reduce “xenophobic outgroup rejection” if administered to all those racist white people who don’t want half a billion African and Middle Eastern Muslim refugees in Europe and North America.

Holland’s migrants are “refugees” and “people like us” — middle class in their countries, handy with English and cellphones, and with means sufficient to have paid the stiff costs of this passage. In reality, they are not like us.

Holland’s Syrian “refugees” are not the stabbers of children in a playground in Annecy or hateful attackers of Jews in Vienna. They are not the Syrian refugees who just in 12 months of 2016/2017, set a homeless man on fire on Christmas in Berlin or, screaming “Allahu Akbar,” attacked and injured four people at a bus station in Lünen. They are not the Syrian refugee who murdered a pregnant woman with a machete and wounded two others at a bus station in Reutlingen.

They are not the Syrian “asylum seeker” who raped a 44-year-old mentally disabled woman in Soest. They are not the 27-year-old Syrian who stabbed and killed a Red Cross mental health counselor in Saarbrücken, or the one who tried to behead 64-year-old Ilona Fugmann who had offered him a job at her beauty salon in Herzberg.

They are not the Syrian “asylum seekers” who were filming and molesting underage girls at a swimming pool in Löbau or the ones who did so in Mariendorf, or the one who sexually assaulted a ten-year-old girl in Tübingen.

Holland’s Syrians are not the “migrant” who went on a “stabbing-spree” on board a train in Bavaria, or the one who attacked passengers on a bus from Berlin to Milan. They are not the “asylum seeker” who blew himself up next to a wine bar in Ansbach and wounded 15 people, or the one in Pittsburgh, who sought to blow up a church for Isis. Nor are they like Abdalfatah who sought refuge in Germany after murdering 36 people in Syria for the Jabhat al-Nusra jihadist group.

No, they are just a cute family with a genial grandpa, a well-married couple, and their nice boy, little girl, and a baby. Not even a Syrian “refugee” family where the father murders his wife because she irritated him, or murders his wife and two daughters and leaves them dead in a freezer.

Holland’s Afghan refugees in the film consist of one English-speaking, kind woman who “helped the Americans” during the Afghanistan war. In reality, Afghan rapefugees sow terror in the heart of Europe’s women. They rape and murder. Again and again, everywhere in Europe, solo and in groups, boasting of it on Facebook, the victim alternately an adult, girl, or boy.

Holland’s sole Afghan is not the 19-year-old Afghan “asylum seeker” who stabbed three people in Ravensburg, or the 41-year-old who murdered a five-year-old Russian boy and severely wounded his mother in Arnschwang, or the one whose sexual intercourse with a woman in Limerick included stabbing her to death in a “frenzied attack “. Nor is she portraying the Afghan migrant who murdered two people in Serbia and then one in Britain, or the one who stabbed seven people in Sweden. Just a kind, educated, Afghan woman mistreated by Polish goons-in-uniform.

Holland’s Africans are not the testosterone-filled, young primitives landing on Europe’s shores by the hundreds of thousands and terrorizing the local population, roasting cats, brandishing their penises or defecating in public, brawling and destroying property incessantly and everywhere. One ought to check out the @RadioGenoa account on X to see much evidence of what they are about. But for Holland they are just a couple of nice, well-behaved teens.

The border has a barbed wire fence. Those nice Syrians, Africans, and one nice lady from Afghanistan are trying repeatedly to breach that fence and each time are repulsed by pitiless, all-black (in character) goons serving as Poland’s Border Patrol. When on the staging side of the barbed wire fence, they are exploited and humiliated by even worse Belarussian goons-in-uniform, and then pushed through that fence into a country whose Border Patrol pushes them back.

They are hungry, thirsty, cold. Some are sick. But then, before Western progressives decided that reality is optional, the law of the Universe has always been that one suffers the consequences of one’s mistakes. Few mistakes can be as bad as to have traveled from faraway Asia and Africa to the Polish border in the belief that it will give way.

Eventually, some manage to get through the fence and, after more harrowing adventures like drowning in a swamp, are aided by a group of young Polish radicals, given food, medical treatment, and shelter and transportation deeper into Poland in the approving glow of the demiurge of this moral fantasy: Agnieszka Holland.

Holland portrays the enforcers of Poland’s territorial sovereignty as primitive cartoon villains, pitiless at the bottom, and fascist at the top. The bottom is the Polish Border Patrol that has no pity even for pregnant women. They toss one over the fence back onto Belarus soil and manhandle many others. Their officer shouts that the pitiful group of migrants mired between the barbed wire and the swamp are “not people” but bullets fired into the heart of Poland.

The only border guard portrayed with sympathetic shading is Jan, whose wife is pregnant and disapproving of his “brutal” occupation. Jan initially participates in the pushback actions but is gradually sickened by the required violence and softens to the point of pretending not to see “migrants” transported into Poland’s interior by another kind Pole.

At the top are the “fascists” — Poland’s slightly right-of-center PiS ruling party that has given the finger to the European Union’s demands for absorbing a “fair share” of the kind of “refugees” that Angela Merkel and the EU were importing by the millions before Lukashenko decided to give them more of their medicine.

Holland, along with most of Poland’s cultural elite, is an outspoken, leftist enemy of PiS — the party that has said No to invaders from alien cultures. She has gone so far into the swamp of “progressive” hysteria that one of her two more developed “good-guy” characters, Bogdan, tells his therapist that he cannot stand the “Nazis” marching in Warsaw under the protection of the “fascist” government — a lie so grotesque as to indicate the warped furniture in Ms. Holland’s brain. Bogdan confesses as well that because of those Polish “Nazis” and fascists he is impotent, cannot sleep, eat, or think.

Vitality returns to Bogdan’s so-dreary life with a loving family in a luxurious villa near Warsaw when he too engages in the “activist” effort. He and his wife and children host three young North-African migrants just smuggled in from the border, invite them to their dinner table, and so on. In a scene characteristic of the twisted minds of Holland and white progressives everywhere, Bogdan’s sons bond with the Africans by joining them in a French rap.

For the white rich kids, knowing French is normal. But what’s more telling is that they, Poles far removed from Africa, have adopted the black culture and they rap in French as expertly as their African guests do. In Poland.

It would never have occurred to Holland to write the scene in the opposite way, with the African guests making an effort to adapt to the culture of their hosts and singing with them a Polish song with the harmonies that are Europe’s culture heritage.

Julia is the other more developed “good guy” character. She is Bogdan’s psychologist and Zoom interlocutor. Moved by the plight of the migrants in the forest near her home, Julia turns from a bystander to a committed rescuer working with the younger activists to smuggle as many migrants into Poland as possible. Maja Ostaszewska, who plays Julia, is a well-known “progressive” and major pro-migrants activist in Poland.

The rest of the positive characters are the bleeding-heart Polish volunteers who help the migrant invaders and made it past the border fence. They are all unalloyed cartoon goodness just as the border guards and policemen who are the barrier against the invaders are the unalloyed evil.

I have written a book and several articles about the horrors that refugees, “refugees,” and migrants from Asian Muslim countries and Africa inflict on Europe. I saw this film while a true African invasion was landing on the beaches of Lampedusa. I am writing this in November, when that invasion is continuing while huge crowds of Muslim imports are marching and rioting all over Europe and the entire Anglosphere, waving black jihad flags, shouting “Death to the Jews,” and generally behaving in ways not seen since the Kristallnacht. I am appalled at Holland’s specious propaganda masquerading as a film drama, her smearing of the one, rare state sane enough to have resisted to rush to self-obliteration, her libelous depiction of the Polish Border Patrol.

I am therefore renaming Green Border as Brown Border. The brown adjective comes from my long-ago Hollywood mentor, an Irish curmudgeon who had elbowed his way to a position of influence in that Jewish-founded-and-dominated industry. Art had long-ago mastered Yiddish, so he taught me some. When it came to a lousy film, hackneyed book, or a revolting painting, he invariably called it dreck. When it came to a lousy human being, he reverted to his native Irish brogue: shite.

Whether dreck or shite, it’s the same color. Green Border is not a work of art but a lying, hysterical outpouring of agitprop by a female raised in a privileged communist home, favoring her ideology over reality, and attacking a polity that, since 1989, no longer adheres to diktats of the Comintern. It’s par for the course that the World Socialist Website attacked Holland’s detractors in a headline reading “The Polish far-right’s vicious campaign against Agnieszka Holland’s film ‘The Green Border’ replete with ‘ antisemitic and fascistic undertones against the film’.”

The reality

Something needs to be said about those “bullets into the heart of Poland” — words that Holland put in the mouth of the Border Guard’s commander, no doubt to imply that he is the epitome of evil. In reality, those words are appropriate and would have been even if the border-busting migrants consisted mostly of women, children and kind men — which they didn’t.

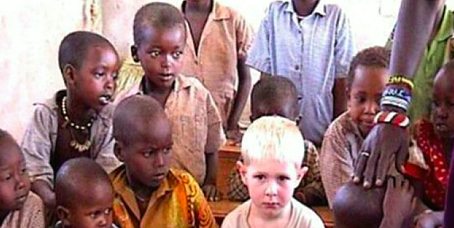

A still frame from Zielona Granica

A still frame from Zielona Granica (

Green Border) shown on the web page of the 2023 Venezia Biennale film festival.

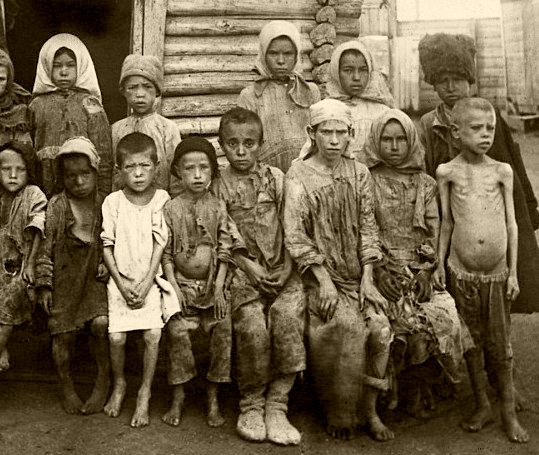

The Poland-Belarus border, with the actual menacing migrants trying to force it.

The Poland-Belarus border, with the actual menacing migrants trying to force it.One now has ample opportunities to see what happens to countries that had a more tenderhearted approach to Muslim refugees and “refugees.” Here is Berlin and here is London. Or New York, or Dearborn, or a hundred other cities in the pathologically altruist West. A European or Europeans-founded country signs its death warrant even if taking in African and Asian Muslim women and children, let along young, military-age men who are the great majority of the invaders.

Continue reading →

Tom Vandendriessche is a member of the European Parliament for Flemish separatist party Vlaams Belang. In the following video he describes the emerging totalitarian state that the European Union has become.

Tom Vandendriessche is a member of the European Parliament for Flemish separatist party Vlaams Belang. In the following video he describes the emerging totalitarian state that the European Union has become.