Immigration-related events are moving rapidly this in Europe summer. The situation is in such flux that now would be a good time to step back and try to get an overview of the process.

Three years ago the dead baby hysteria, followed by Chancellor Merkel’s invitation to the world (“Y’all come in and set a spell, bitte!”), launched the Great European Migration Crisis. Since then I’ve read hundreds of news articles and analyses about the flow of “refugees” and the reactions to their violent and fragrant arrival in Western Europe.

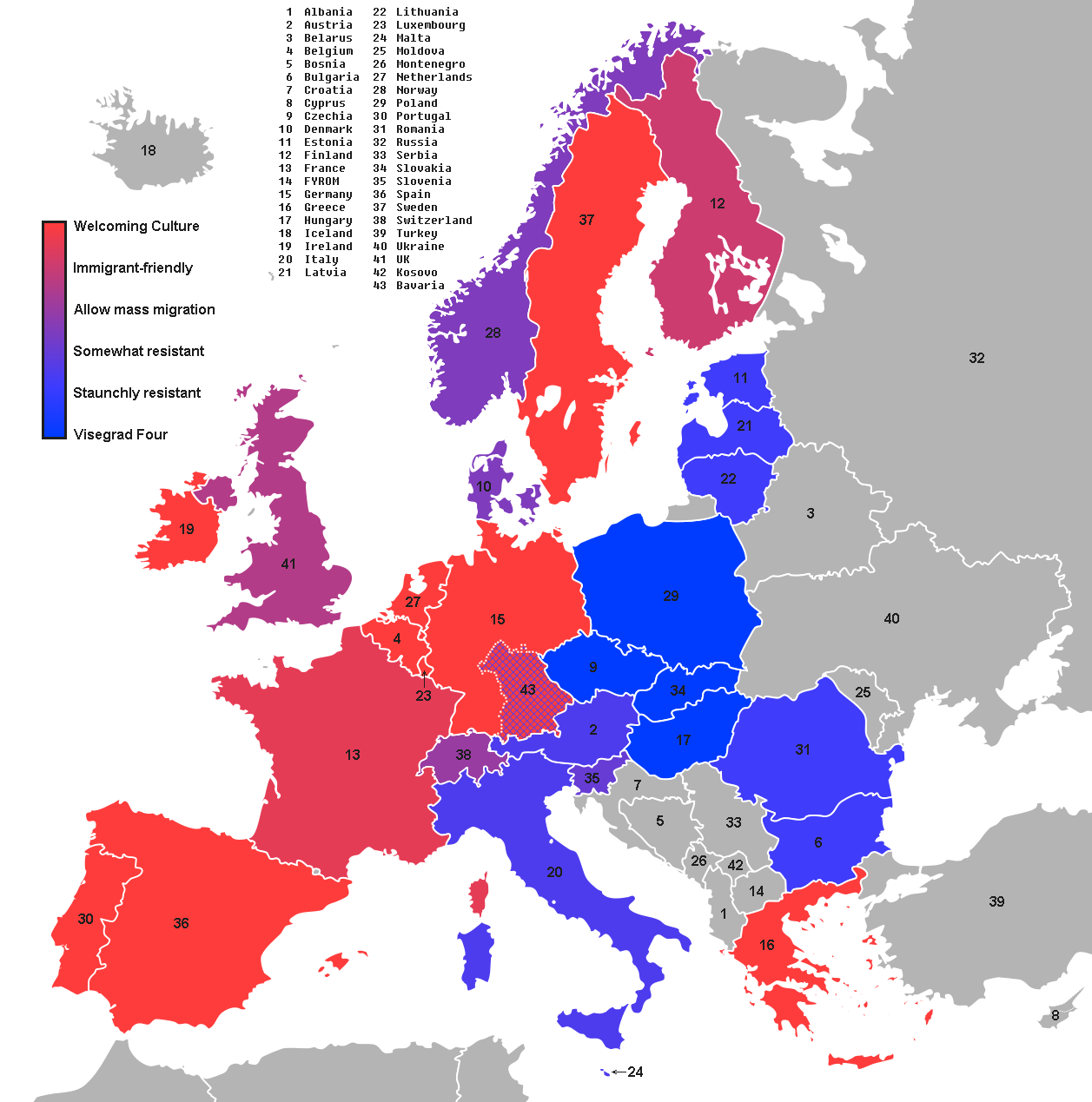

After digesting all that information I created the following map, which presents my subjective evaluation of the different approaches to migration by various European countries. I’ve rated the policies of 28 different countries (the EU 27 minus Croatia, plus Switzerland) on a scale from 0 to 100, from zero (red) for the open-borders attitude of the “Welcoming Culture” to 100 (blue) for the absolute refusal of mass migration by the Visegrád Four (Hungary, Poland, Slovakia, and the Czech Republic). Data from the last six months weighs more heavily in the score assigned to each country — for example, Spain and Italy recently changed governments, which has strongly affected each country’s migration policy.

Immigration policies in Europe, Summer 2018 (Click to enlarge)

Immigration policies in Europe, Summer 2018 (Click to enlarge)The grouping of countries based on their stance on migration bears a striking resemblance to the division of Europe into East and West by the Iron Curtain. This is especially true if we roll the clock back three months — back then Italy and Bavaria would have been quite red. And the analogy becomes even more apt if we remember that Austria was occupied by Soviet troops until 1955, which gives it one foot in the Eastern camp.

The biggest change in the past three months has been the formation of a new anti-immigration government in Italy. The “xenophobia” of the East Bloc has now broken through the razor-wire curtain and gained a foothold in Western Europe. No wonder EU politics is in such turmoil! After failing to contain the “anti-European” attitudes of Poland and Hungary, Brussels now has to contend with Matteo Salvini. Italy is one of the “big four” pillars of the European Union, so its defection to the anti-migration side carries enormous significance for continental politics.

The situation is metamorphosing rapidly, but before we analyze the process of change — the “delta”, as they say in the military-industrial complex — let’s go over the snapshot of current European migration policies.

The Visegrád Four

Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán was the first major European political leader to (1) understand the larger significance of the refugee crisis of 2015, and (2) act rapidly to counteract the nexus of globalist actions that threatened the stability of the Hungarian state. In doing so he made himself an obstacle to the no-borders coalition, especially the “American philanthropist” George Soros. The reaction to Mr. Orbán’s building of the fence helped clarify the East-West divide, and strengthened the solidarity of the Visegrád Four. Each country now supports the others’ positions, and each vows to veto any action by the EU (the European Commission requires consensus to implement a sanctions regime) that would harm the other members. Taken individually, each V4 country is no match for Germany or France, but when they act in concert the four countries become a formidable thorn in the flesh of the Brussels oligarchy.

The movement of Italy and Austria (and even Bavaria) towards the Visegrád Four position allows Hungary to — as Barack Obama has so frequently said — punch above its weight.

Austria

The most recent Austrian election resulted in a coalition government headed by Sebastian “Boy” Kurz (ÖVP) as chancellor and Heinz-Christian Strache (FPÖ) as vice chancellor. Mr. Kurz may well be a cynical opportunist who has simply trimmed his sails to the wind, all the while remaining loyal to his mentors in the Davos crowd. However, to maintain his position he has to give at least the appearance of acting decisively to deal with the migration issue — hence the recent law targeting “radicalization” in Austrian mosques (see Christian Zeitz’ analysis). Part of that appearance will of necessity include the reduction of violence and disorder brought to Austria by Muslim immigrants. Any failure to achieve discernible results will endanger his chancellorship. For that reason one may expect him to stay the course, at least for the time being.

Mr. Kurz’ alignment with Italy, Hungary, and Bavaria bodes ill for Chancellor Angela Merkel and the mandarins in Brussels. A counterweight to their power is forming on their southeastern flank, and the resulting political crisis looks to be the most turbulent since the fall of the Iron Curtain and the reunification of Germany.

Italy

The new coalition government in Italy is shaking the very foundations of Barad-dûr in Brussels. The Five-Star Movement is more or less a traditional populist party, but the Lega Nord is full-on anti-immigration. Interior Minister Matteo Salvini has hit his stride early, turning back the refugee ferries and threatening to impound any NGO “rescue” vessels that make port in Italy. Unlike Chancellor Kurz, Mr. Salvini has never changed his tune — almost ten years ago, when I first started paying attention to him, he was the same anti-migrant firebrand that he is today. He shows no sign of being cowed by threats from Brussels; it’s no wonder that emergency summits are being hastily convened in reaction to him.

Since the new government was formed, the Lega has shot ahead of the Five-Star Movement to become the most popular party in Italy. If another election were to be held, Matteo Salvini would most likely end up as prime minister.

Eastern Europe

When I use the term “Eastern Europe”, I refer to the Baltic republics, Romania, and Bulgaria. (The Visegrád Four plus Austria comprise Central Europe. Strictly speaking, Moldova, Ukraine, and Belarus could also be considered Eastern Europe, but their political affairs are more closely associated with Russia, whether for or against, so I’m leaving them out of this analysis.)

Eastern Europe has the good fortune not to be attractive as a final destination for migrants — their welfare benefits are much less generous than those further west, and they are less reticent about dealing harshly with the criminal proclivities of foreigners. Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania have the added advantage of being largely off the route for most of the migration flowing into Western Europe.

Bulgaria and Romania have their share of migrant camps, full of angry, resentful Third-World “refugees” who are impatient to get out of those Black Sea backwaters and into the promised land of Germany or Sweden. The crime and disease the migrants bring with them spills out of the camps and into the adjacent towns. News outlets in those countries are blessedly un-PC, so the word gets out, and members of the general public who may once have been indifferent are now becoming anti-immigrant.

Continue reading →

I went to the retinologist this afternoon for my monthly examination, and received another injection in my left eye (for wet macular degeneration). Everything went as expected.

I went to the retinologist this afternoon for my monthly examination, and received another injection in my left eye (for wet macular degeneration). Everything went as expected.

A man deliberately drove a van into the building of the offices of De Telegraaf in Amsterdam before exploding it. After his second attempt to ram the building, the driver got out and detonated some sort of explosive in the back of the van before fleeing on foot. No suspects have been arrested.

A man deliberately drove a van into the building of the offices of De Telegraaf in Amsterdam before exploding it. After his second attempt to ram the building, the driver got out and detonated some sort of explosive in the back of the van before fleeing on foot. No suspects have been arrested.