This is the final installment of a story by Matthew Bracken, which has been serialized here in four parts.

Previously: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3.

Update: All four parts of this story are now available as a single document, in two formats:

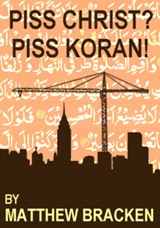

Piss Christ? Piss Koran!

Part Four: Resolution

by Matthew Bracken

“Your call, smart guy.” The phone connection made a click and the line went dead.

Mike wasn’t a kid. He knew that he wouldn’t live forever. He’d had enough brushes with death to understand that a healthy old age was not guaranteed in the contract. He’d been standing next to men who had stepped the wrong way, and fallen. He’d helped pull a man’s body off a concrete footer where he’d been impaled on an uncapped rebar stake. Just two stories down, and dead as a nail. Laughing and joking the minute before. A paragraph in the back of the paper, if that. There but by the grace of God.

Before he’d climbed the tower, Mike hadn’t planned out how the stunt would finish up. He figured that at the very least, he’d be arrested for trespassing. In fact, he didn’t even have a bottle of piss. It was apple juice, in case he spent the whole day up there and ran out of bottled water. He just wanted BCA News to be forced to publicly account for how casually they accepted Serrano’s Piss Christ as “art,” showing it on their website for years, when they were too cowardly to ever show a single peep of an unpixilated Mohammed cartoon. But finishing the morning by crawling down the twenty ladders, and hoping that some police officers would arrive to protect him from the gathering crowd of enraged Muslims?

No way. Not even if he had believed Vic Del Rio about the police escort, and he didn’t believe that lying weasel for a second. Not after Del Rio set him up for the mayor’s phone call, and the coordinated SWAT helicopter assault. Now there was only a single thin line of police barricades across the middle of 53rd Street, but there were no police officers standing behind it. Frank Salerno had said that the mayor wanted him dead. That, he believed. Some kind of a deal had been struck, but it wasn’t with him. It was between the mayor and the leaders of the local Muslim community.

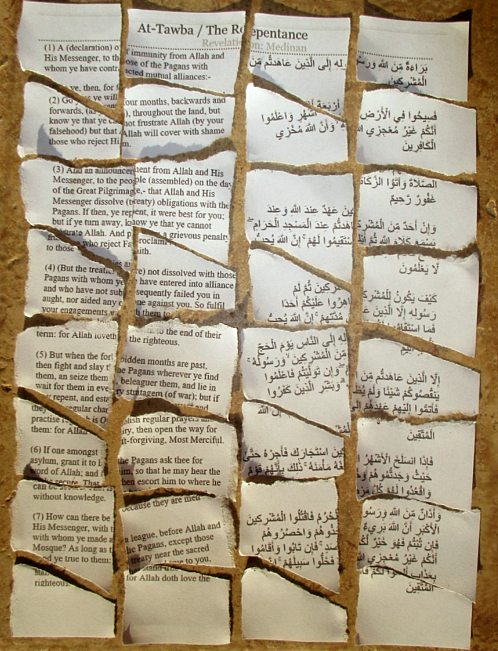

So even if he wanted to go, to slip away quietly, the mob now unrolling their prayer rugs on 53rd — already angry enough to chew rebar and spit bullets — would see him coming before he was halfway down the twenty ladders. In their minds, he had already desecrated their Holy Koran by tearing up Sura 9:5, the Verse of the Sword.

So the die was cast. Well, nothing lasts forever. It had been a great life, and he’d had a wonderful wife. At least it was a gorgeous August morning in Midtown Manhattan, the rising sun casting beams and shadows down the length of 53rd. If this was his day to go, he thought he might as well make the best of it. He looked at his watch. It was 8:33, so he had just under a half hour. That is, if the mob was going to wait until after their morning prayers to stop the two blasphemies.

He picked up his iPhone to see what they were covering on BCA. A reporter was standing in front of a wave-pounded marina in Cabo San Lucas while Hurricane Eliza swept through. He selected his other television network preset buttons, and saw that none of them were covering the events around 6th Avenue and 53rd Street in Midtown Manhattan. Vic Del Rio had been right. The plug had been pulled on his stunt. He put the ear bud from his little Sony radio back in. On WNYR, he was surprised to hear Jerry Conroy’s voice, but it only took him a moment to understand that it was a pre-recorded “best of” show.

Meanwhile, beyond the puny little barricade just to the west of the crane, 53rd Street was rapidly filling up with devout Muslims who had heard the imam’s call to action. While he watched, he saw something glint in the sunlight. A man in a tan robe unrolled his prayer rug, revealing a sword, which he waved in circles over his head. Then the sword went against the pavement, his prayer rug concealing it.

Mike tried calling the WNYR studio office line again, but got a busy signal. He knew it would be useless to call the other radio and television stations on his list. But he also knew that there must still be cameras on him, even from across 53rd in the Grand Hotel. He found his spiral notebook and his Sharpie, and was considering which sticky-noted verse advocating the murder, plunder and rape of the infidels to tear out of the Koran next, when he heard an insistent rapping behind him. He looked around his poncho lean-to shanty toward the corner office of the bank building, and saw a crowd of people, at least half of them in police uniforms.

The woman from the other office was there again, holding another file folder message against the window. It read >call this number< followed by nine digits. He didn’t recognize the area code; it wasn’t from New York. It was hard to see around the shanty, so he unclipped the bungee cords from the corners, rolled it up, and put it away in his pack. With the BCA cameras a hundred yards across 6th Avenue turned off, it no longer made sense to hide from the eyewitnesses who were nearest to him, police or not.

He still had a zip-lock bag with unused prepaid flip phones, so he used a fresh one to call the number. It was picked up and answered on the second ring. He heard “Hello?” It was a woman this time.

“Do you know who this is?” asked Mike.

“Of course, silly, the whole world knows! I’m glad you called. The show must go on, right?” She had a hillbilly accent. Middle-aged and gravelly, like she was a smoker.

“How? BCA is back to showing the hurricane.”

“Oh, we don’t care about BCA. If you’ll take another caller, we’ll make sure it gets on the radio. And it’ll get on the internet too.”

“How?”

“To tell the truth, I don’t rightly know how. Somebody else is handling that side of it. But they seem pretty sure that they can keep you on the air, if you want to be. So, do you want to be?”

“Of course I do. That’s why I’m up here.”

“That’s the spirit, Mike! Well, I just got the high-sign, and they say we’re live on a Ko-rean radio station in Newark, New Jersey right now, if you can believe it. Ko-rean!”

“Korean? But that means —”

“Don’t worry, it’ll be in English today. We just put out the station information by text message. All the union guys in New York City are getting them as we speak, at least, that’s what I’m told. And it’s going on the internet, too, somehow. Audios and videos; it’s being filmed from every which way, that’s what I’m told. I don’t really understand how it all works, but they say that if that creepy mayor of yours takes that Ko-rean radio station off the air, they have more stations lined up right behind it. All right?”

“I guess so.” If it was over her head, it was way over Mike’s. But he could see that on the other side of the window walls of the corner office, several people were holding up smart phones, so for sure, he was on video.

The Southern lady said, “Now, you look for another number, and use another phone. You have a very special caller. Good luck, and God bless.”

“Wait a minute —” But the line had gone dead.

He looked back to the building. The woman with the file folder was showing another number. He chose a new flip phone, and called it. It rang once and was picked up.

“Is this Brooklyn Mike?” It was a girl’s voice, or a young lady’s, speaking in unaccented American English.

“Yes, it’s me, who is this?”

“For today, my name is Amina. Some people that I trust said that I can talk to you, and that everybody will hear my story.”

“They tell me the same thing, Amina, so go ahead, I guess.” Mike looked at his watch. Twenty minutes to nine. It wasn’t his plan at this point to take another caller, but really, what plan did he have left?

“Thank you. I wanted to do this for a long time. Mike, have you ever heard of a lady named Ayaan Hirsi Ali?”

“Sure, I know about her. She’s from Somalia, and she wrote a book called Infidel, and another book called Nomad.” Both had come highly recommended, and Mike had read them while he was doing his own research on Islam. They were amazingly insightful. Brilliant, really.

In a soft voice, the girl said, “Ayaan Hirsi Ali is from Somalia, as you said, and she escaped from Islam. So today, she has to live in hiding, because she is an apostate Muslim. Well, I too have escaped from Islam, and I too am in hiding, but I was born in America. I was born in America, and I’m in hiding!” Amina paused to catch her breath, and gather her thoughts. “I was only allowed to go to a normal American high school for two years, tenth and eleventh grades. I had to wear the hijab, and I was watched for every minute I was out of our house. And the hijab had to be tight around my face, and I had to wear long clothes, almost like a burka, so that just my hands and my face would show.”

She said, “Maybe you have heard that some Muslim girls like to dress that way, but what about the girls who hate it? What about them? When I unwrapped my hijab and wore it loose like a scarf, and my hair would show, I was beaten for it by my father at home. No matter where I went, I was spied on, even by my own brothers. If I was seen talking to regular American kids, not Muslims, just talking, like friends, I was beaten. I was never allowed to make any friends on my own, never. No sports, no drama club, just straight home. My father checked my phone every night, and he told me that if I ever had an American boyfriend, he would kill me. Kill me! And I believed him, because he already beat me all the time. But never on my face, so the marks wouldn’t show. I tried to find just a little freedom in my life, and he found every little piece, and smashed it flat. He thought I was becoming Americanized — that’s what he called it — but I was born in America! Why shouldn’t I be Americanized? I was an American, but I was a slave.

Continue reading →

Apollo got very angry and barked out that Duke and Spike were the leaders of the wolfophobic bigots, and we should be ashamed of how badly we spoke of our new canine cousins, and all canines are equal. Now that they had arrived on peaceful Dog Island, they would live in peace with us. Believe it or not, most of the show dogs were nodding their agreement at this utter nonsense.

Apollo got very angry and barked out that Duke and Spike were the leaders of the wolfophobic bigots, and we should be ashamed of how badly we spoke of our new canine cousins, and all canines are equal. Now that they had arrived on peaceful Dog Island, they would live in peace with us. Believe it or not, most of the show dogs were nodding their agreement at this utter nonsense.

But this response can only happen when free men and women first look around them at their children and their children’s children, contemplate what such a future may hold for them and theirs, and then, lastly, inwardly ask of themselves: “What am I doing? Why is this happening? Where have I gone wrong?” Thus, in the face of this observed reality, the whole rotten-to-the-core 21st-century global elite’s collective power grab may be peeled back layer by layer. Once full understanding and the fear induced by a realisation of impending tyranny or extinction have together overcome the false doctrines endlessly iterated by the deconstructionists, it is then, and only then, that mass counter-movements can arise, reset the course of their lives and determine their own destiny according to their needs and desires.

But this response can only happen when free men and women first look around them at their children and their children’s children, contemplate what such a future may hold for them and theirs, and then, lastly, inwardly ask of themselves: “What am I doing? Why is this happening? Where have I gone wrong?” Thus, in the face of this observed reality, the whole rotten-to-the-core 21st-century global elite’s collective power grab may be peeled back layer by layer. Once full understanding and the fear induced by a realisation of impending tyranny or extinction have together overcome the false doctrines endlessly iterated by the deconstructionists, it is then, and only then, that mass counter-movements can arise, reset the course of their lives and determine their own destiny according to their needs and desires.