Thomas Bertonneau’s latest essay is a review of a book that was published more than sixty years ago and is not available in digital form.

Mika Waltari’s Dark Angel (1952) — A Novel for Our Time

by Thomas F. Bertonneau

Introduction. The name of the Finnish novelist Mika Waltari (1908 — 1979) reached the peak of its currency in the mid-1950s when many of his titles had transcended the isolation of their original language to come into print in English, French, German, Italian, and Swedish. One of these, The Egyptian (1945) had reached the big screen in 1954 in a lavish Hollywood production directed by Michael Curtiz, with a cast that included Edmund Purdom, Victor Mature, and Jean Simmons. Curtiz’s film adhered closely to Waltari’s story, which concerns the attempted religious reforms of the pharaoh Akenaten, which Waltari, the son of a Lutheran minister and a serious student both of theology and philosophy, regarded as an early instance of ideology. Basing his fiction on the best information available at the time, Waltari strove to show how, despite the sincere intention of the reformer, the reforms themselves so contradicted Egyptian tradition that they devastated the society. The novel operates intellectually at a high level. So does Curtiz’s cinematic version, which likely explains its poor box-office on release. The Hollywood connection nevertheless boosted Waltari’s foreign-language sales and meant that his books would remain in print into the 1960s. Today Waltari’s authorship is largely forgotten, along with those of his Scandinavian contemporaries such as Lars Gyllensten, Martin A. Hansen, Pär Lagerkvist, Harry Martinson, Tarje Vesaas, and Sigrid Undset. Anyone who has seen the film Barabbas (1961) with Anthony Quinn in the title role has, however, had contact with Lagerkvist, on whose novel director Richard Fleischer drew.

All of those writers might justly be characterized as Christian Existentialists, heavily influenced by Søren Kierkegaard, who saw their century, the Twentieth, as an era of extreme crisis at its basis spiritual, and who saw the ideologies — the rampant political cults — of their day as heretical false creeds that fomented zealous conflict. It is unsurprising that such a conviction should have taken hold in Scandinavia. Two of the Scandinavian nations, Denmark and Norway, had endured conquest and occupation by Germany in World War II. Sweden avoided that fate, but as Undset wrote in her account of escaping the German invasion of Norway, most Swedes expected disaster to strike at any time from 1940 until the end of hostilities, either from the Germans or from the Russians — or possibly from both, with the nation becoming a battleground. In Finland, which had only won its independence in 1918, first by rejecting Russian rule and then by defeating a Communist insurrection within its own borders, the sense of acute crisis realized itself in the Soviet attack in the winter of 1939-40, during which Waltari worked in Helsinki in the Finnish Government’s Information Bureau, and again in the subsequent Continuation War of 1941 through 1944. These events are the immediate background to Waltari’s composition of The Egyptian, and they are by no means irrelevant to Dark Angel, published seven years later.

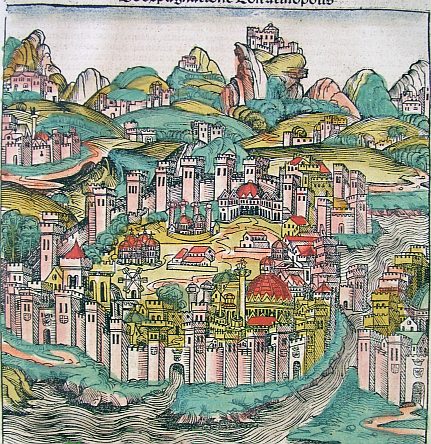

I. Dark Angel is somewhat less ambitious philosophically than The Egyptian, but it is perhaps more relevant to the present moment in 2017 than its precursor-novel in Waltari’s oeuvre, concerning as it does the Fall of Constantinople, and with it the remnant of Eastern Christendom, to Sultan Mehmed II’s Ottoman Turkish Jihad in the summer of the year 1453. In Waltari’s novel, incidentally, Mehmed is called Mohammed after the Arabic pattern of his Turkified name. In Dark Angel, as in The Egyptian, Waltari makes use of allegory. The shrunken, dispirited Greek-speaking Christian empire of the East, as it confronts the seemingly inexorable westward encroachment of militant Islam, stands in for the postwar West, as it confronts a militant, expansionist Communist empire stretching from Moscow to Peking and beyond. The enemy without — Islam or Communism — fosters enemies within: Fellow travelers who despise their nation and its ways and pessimists who have given up hope to await the end in moods of hedonism and cynicism. Nevertheless, neither Dark Angel nor The Egyptian can be reduced to allegory. Dark Angel in particular commemorates one of those epochal events in Western history, and particularly in the history of the West’s 1400-year hostile entanglement with militant Islam, that has vanished down the memory hole, and whose re-conjuration political correctness resists.

As in The Egyptian, again in Dark Angel, Waltari heightens the immediacy of his storytelling through the use of the grammatical first person and through the repletion of the background with carefully researched historical detail. The Egyptian presents itself as the memoir, written in old age, of the physician Sinuhe, whose profession brings him into contact with Akenaten, and who therefore witnesses the events of Akenaten’s regime from close at hand. Dark Angel purports to be the diary of the mysterious Jean-Ange, Giovanni Angelo, John Angelos, or Ioannis Angelos, an apparent soldier of fortune of Greek ancestry who shows up in Constantinople a few weeks before the onset of the fateful siege. Like Sinuhe in The Egyptian, Angelos corresponds to the typical protagonist of the mid-Twentieth Century Existentialist novel: He is the deracinated man, part cynic, part skeptic, who has felt the tug of a redemptory Tradition and has resolved to root himself again, to the extent possible, in what he can identify as his ancestral ilk. His actions are by way of paying off a belatedly recognized debt; and they seek to affirm a patrimony as well as a more general cultural and religious kinship. Angelos functions additionally as a living Rorschach image for other characters, who, recognizing him as somehow familiar and rather haunting, project on him their own otherwise hidden thoughts and traits. An angel is a messenger — and in the stranger’s presence people experience the compulsion to deliver up their own messages, as though in confession, whether they mean to or not.

In Angelos, Waltari has conjured a pure fiction, but he draws most of his characters from the historical annals. One might read John Runciman’s classic study of The Fall of Constantinople (1965) alongside Dark Angel and encounter the same tragic personae. In Waltari’s novel, for example, Emperor Constantine XI Palaeologus is a character; so too is the Megadux or Admiral of the Fleet Lukas Notaras, with his daughter, the beautiful Anna, and his two sons. The ex-Keeper-of-the-Seal George Scholarius, now referring to himself as the monk Gennadius, takes a role in the tangled plot. The Genoese strategist Giovanni Longo Giustiniani, who brings his mercenary army to participate in the city’s defense, befriends Angelos, who becomes his lieutenant. On the Muslim side Waltari gives his readers Sultan Mohammed, in whose retinue Angelos has previously served, such that both the Greeks and Latins of Constantinople plausibly mistrust him. A minor character on the Constantinopolitan side, the German engineer John Grant, represents an emergent scientific and technical worldview that sees itself as entirely extra-moral. Waltari knows the layout of the Fifteenth-Century imperial capitol the way he knows the back of his hand. Runciman’s Fall with its maps makes itself useful as a Baedeker to the novel. It helps to know where the Blachernae Palace stands in relation to the Romanos Gate and other topographical details.

Waltari, establishing an atmosphere of tenseness from the beginning, makes it clear that Western — that is to say, Catholic-Orthodox — doctrinal factionalism contributed mightily to making the Byzantine rump-empire vulnerable to Ottoman aggression, despite the city’s formidable walls. So too did the cowardice of key parties among the Greeks and the Latins. The Palaeologus dynasty had in fact seen the writing on the wall since the reign of Manuel II, Constantine’s father. During his emperorship, Manuel undertook a grand tour of Europe as far as the court of Henry IV of England seeking European support for Eastern Christendom. Manuel also sent an ecclesiastical delegation to Ferrara in Italy to negotiate with Rome concerning doctrinal differences; after a few months the so-called Council moved to Florence, but it was disorganized in both places. As Runciman writes, “the detailed story of the Council makes arid reading,” but the conclusion, pressed for by Manuel’s eldest son John (who would reign as John VIII) against his father’s wishes, was a declaration of union that the ordinary constituents of Orthodoxy regarded as a betrayal. Nevertheless, in the hope that it would facilitate direct aid from the Catholic West should a crisis come, Constantine, on succeeding John, publicly upheld the declaration and permitted the filioque of the Latin Mass to be uttered during the liturgy in Hagia Sophia.

Dark Angel begins just as one such liturgy ends. In the characteristic Byzantine manner, participants in the Mass leave the church in strict hierarchical order. Standing outside Hagia Sophia, Angelos sees Constantine and his retinue emerge. He remarks of Notaras that “his glance was keen and scornful, but in his features I read the melancholy common to all members of ancient Greek families.” Angelos knows Notaras to be an opponent of union. He supposes that the Megadux, although obliged to attend the service, was “agitated and wrathful, as if unable to endure the deadly shame that had fallen on his Church and his people.” As the palace guard brings forward the retinue’s horses, Angelos hears shouts from the crowd: “Down with unlawful interpolations” and “down with papal rule.” Breaking away from the emperor, Notaras addresses the crowd. “Better the Turkish turban,” he shouts, “than the Papal miter!” The crowd repeats the slogan. Angelos compares the sentiment to the one voiced by another crowd centuries before: “Release unto us Barabbas!” Later, the crowd shouts after Constantine, “Apostata, Apostata!” Angelos, who attended the discussions in Florence fourteen years earlier, senses the spreading dementia in the city and knows that it spells doom.

II. Readers learn of Angelos’ biography bit by bit throughout the story. Raised in Avignon by a Greek-speaking father who at one time had been blinded (he said, by thieves), he was, when just attaining his majority, accused of having murdered his father in order to come into a patrimony that turned out not to exist. He suffered arrest and torture, but was released through the intervention of Cardinal Giulio Cesarini, whose secretary he became in Ferrara and Florence. He went with Cesarini in the Papal campaign against the Turks in the Balkans, during which, at the Battle of Varna, in Bulgaria, the Hungarian contingent turned on the Papal troops and assassinated Cesarini. After Varna, Angelos “took the Cross.” The phrase has a peculiar implication. It refers to Angelos’ affiliation with “The Brotherhood of the Free Spirit,” an actual medieval heresy that sought to hasten the Kingdom of God. Angelos tells Anna about the Brotherhood. Acknowledging “only the four Gospels,” Angelos says, the brethren “reject Baptism” and “recognize one another by secret signs.” Later, as his story goes, “I dissociated myself from them, for their fanaticism and hatred were worse than any other bigotry.” Angelos became a wanderer — like almost every other Waltarian protagonist — and, speaking French, Italian, Latin, and Greek — ended up a mercenary soldier and advisor both to Murad, Mohammed’s Sultan-father, and to Mohammed himself. With Murad, whom he describes as a non-fanatic, he became friendly, but with the son his relation was entirely contractual. Fleeing Mohammed, he came to Constantinople to vindicate his Greek origin.

Secret societies, cabals, and conspiracies belong, as Angelos sees things, to the increasingly corrupt and morally relativistic world, of which decrepit Byzantium stands as symbol. The promise of justice typically conceals the lust for power. Angelos’ own story goes much deeper. Toward the end of Dark Angel, just before the catastrophe, Angelos confesses what other characters and the reader himself have already half-guessed. “My father was half-brother to old Emperor Manuel,” he tells Anna; and “Emperor John” — he means John V Palaeologus, not John VIII — “was my grandfather.” Before he claimed the crown, the elder John “went to Rome and Avignon, forsook his own religion and acknowledged the Pope although without compromising either his people or his church.” Returning to Constantinople, John assumed the Imperium with promises of support from the Pope and the Doge, but the treachery of his son Andronikos and the inaction of the West forced him to make a compromising treaty with the Turks and to name his son Manuel as his heir, who would become Manuel II. As Angelos affirms to Anna, however, his father, the fictitious half-brother, was “the only lawful successor.” Manuel then sent the agents to blind his rival and make trouble for the rival’s son, Angelos. Thus, not Constantine, but Angelos, himself, is the legitimate monarch: “I am the Basileus, but I desire no power.” Angelos wishes only “to perish on the walls of my city,” as he says. In The Egyptian, Waltari uses a similar plot-device. Sinuhe discovers to his consternation that he is a natural son of the previous Pharaoh and by that virtue more rightly the monarch than Akenaten, but he wants nothing to do with the station.

The fact that many other people have recognized Angelos and know him as rightful heir to the throne (John VIII left no issue, so the crown passed to his cousin, Constantine) helps to explain his anomalous status in Constantinople. He might well be the Sultan’s spy. Notaras, for example, assumes him to be a spy and sees him therefore as a possible ally and a convenient messenger between himself and Mohammed. The reigning Constantine might well harbor a sentiment similar to Angelos’ own, that “when I reverted to the Church of my fathers it was also the apostate John who in me won back his part in the holy mysteries.” If he knew of Angelos’ legitimacy, he would have a humbling sense of his own fortuitous position. Constantine, too, has made it clear that he will never surrender the city to the Sultan, but that he intends to die in its defense. Waltari quotes Constantine’s actual letter to the Sultan. In Waltari’s novel Constantine appears to have issued writs guaranteeing Angelos’ safety. Constantine treats Angelos like fellow royalty. Previously, Sultan Murad had treated him in the same way, and Murad’s son Mohammed, knowing who Angelos was, presumably kept him in service as leverage in negotiations with the Greeks. It is truly Byzantine, in the pejorative sense of that term, and forecasts the dynastic complications of Frank Herbert’s Dune novels or George Martin’s Game of Thrones, except that in Dark Angel Waltari is writing something like a documentary fiction.

Waltari likes to let his protagonist converse with historical personages. These passages of the story have considerable interest and read rather like Platonic dialogues on politics and theology. Early in his Constantinopolitan residence, Angelos seeks out the monk Gennadius who, like Notaras, reviles the union and prefers the Sultan to a theologically compromised Basileus. Much irony attends Gennadius’ conviction. As George Scholarius he had been a key figure in the Florentine conciliation “who signed the union with the rest.” Gennadius has recently, Martin-Luther style, posted a screed on the gate of the Pantokrator monastery denouncing the union and all who comply with it. He spits out the words “anathema” and “apostata” as soon as he sees Angelos. When Angelos reminds him that they once had friendly relations in Florence, Gennadius replies that it was George Scholarius whom his visitor knew and Scholarius is dead. Angelos detects in Gennadius the same psychic distortion that he had detected in Notaras: “His fever and spiritual agony were not feigned; truly he suffered and the death sweat of his people and his city stood on his forehead.” The monk’s ordeal has not, however, yielded up clairvoyance, but on the contrary his wild resentment has left him deluded. In the critical moment, when the city’s defense must be integral, he has sown dissension. Gennadius tells Angelos that “through my tongue and my pen God will scourge [the people] for their grievous betrayal.” Like Notaras, Gennadius has convinced himself that “our Church will live on and flourish even in the Turkish Empire, under the protection of the Sultan,” who “makes war not on our faith but on our Emperor.” Constantine is, according to Gennadius, “a worse enemy to our religion than Sultan Mohammed.”

George Phrantzes, Constantine’s Chancellor of the Exchequer and close advisor, summons Angelos to the Blachernae Palace for interrogation. Phrantzes accuses Angelos of being Mohammed’s spy. A dossier details Angelos’ personal relation to the Sultan. Angelos refuses to deny it even affirming that, “Indeed, I loved Mohammed,” but he qualifies the statement by saying, “as one may love a splendid wild beast, while aware of its treachery.” Mohammed comes on stage, so to speak, only at the end of Dark Angel, although the Byzantines see him in the distance as soon as the siege begins, but he is the topic of discussion throughout. It is through Angelos’ characterology of Mohammed that Waltari makes his critique of Islam, a word that appears only sporadically in the novel’s pages. That critique runs oblique to a number of current, journalistic notions concerning the desert cult and might come as a surprise to no few contemporary critics of the Koranic dispensation. It is quite usual, for example, among critics of Islam to refer to it as an anachronism: A Seventh-Century tribal cult, totally out of place hence implacably hostile to modernity. Waltari — supposing Angelos to articulate Waltari’s insight — sees the matter in a different light.

In a conversation with Giustiniani, the Genoese condottiero, Angelos narrates a horrific tale about Mohammed, the spelling of whose name lends it useful ambiguity, after telling which he proffers his thesis. Angelos affirms to Giustiniani that, “Mohammed is not human,” a proposition that he repeats when Giustiniani at first laughs off the proposition. “Perhaps he is the angel of darkness,” Angelos says; or “perhaps he is the One who shall come,” a reference to Joachim of Fiore’s messianic Thirteenth-Century theory of the Three Ages, whose chiliastic view of history informed the beliefs of the Brotherhood of the Free Spirit and had echoes in Byzantium. Angelos continues: “But don’t misunderstand me… if he is a man, then he is the new man — the first of his kind. With him begins a new era… which will bring forth men very different from the race we know.” Such men will be “rulers of earth, rulers of night, who in their defiance and arrogance reject heaven and choose the world.” According to Angelos, these men “will bring the heat and cold of hell to the earth’s surface,” and “when they have subjugated land and sea they will build themselves wings in their demented lust for knowledge, that they may fly to the stars and subjugate even them.” Elsewhere in Dark Angel, Waltari emphasizes the technically up-to-date quality of Mohammed’s siege. He has hired Europe’s foremost cannon-builder, a Hungarian by the name of Orban, and deploys sophisticated siege-engines.

III. What is the horrific tale that gives rise to Angelos’ conclusion that the Sultan is not human? Mohammed acceded twice to the throne. The first time in 1444, when he was barely twelve, he had his crown snatched away by his father. The second time in 1451 he was barely in his majority, but his father had died. The shock-troops of the Sultan’s standing army, the Janissaries, regarded their new command-in-chief as a mere boy whose military virtues were not apparent. That much is fact. In Angelos’ story, Mohammed manipulates the scornful soldiery by receiving a veiled girl, who has been taken in slavery, and disappearing with her into his tent for three days. On emerging, the troops mock the Sultan; they toss clods of earth in his direction. Mohammed addresses them, saying that if they could see the girl naked, as he has, they would understand his passion. He then drags the girl out, stripped to the skin, saying, “Look, and confess that she is worthy of your Sultan’s love!” Angelos continues: “Then his face darkened with rage, he… commanded, ‘Bring me my sword!’”; whereupon, pushing the victim to her knees, “he seized her by her hair and at one stroke severed the head from her shoulders, so that the blood spurted onto the nearest janissaries.” The demonstration quelled the mutiny.

Is the story historical or fictitious? It is likely fictitious but at the same time it is perfectly consonant with what the biographers record about Mehmed. Both Runciman in his Fall and Franz Babinger in his Mehmed the Conqueror and his Time (German 1953 — English 1978) tell the same story about Mehmed’s second accession. The young widow of Murad, Mehmed’s stepmother, had come to the throne-room to express to the new Sultan her grief over the death of her husband who was Mehmed’s father. During the meeting, as Babinger recounts it, “Mehmed dispatched Ali Bey… to the women’s quarters to drown Küçük (Little) Ahmed Çelebi, Murad’s youngest ‘porphyrogenite’ son, in his bath.” The very same stepmother was the child’s birth-mother; and as the child’s father was Murad, the child was also Mehmed’s half-brother. Ahmed’s mother was a Serbian-Christian woman. Babinger also records how Mehmed had “since childhood… hated everything connected with Christianity and had repeatedly declared that once he mounted the throne he meant to destroy the Eastern Empire and all Christianity, root and branch.” From Babinger again comes the story relating that “often at night [Mehmed] strolled the city [of Edirne] incognito, accompanied only by two intimates, to inform himself of the state-of-mind among the population and in the army.” If the masquerade struck anyone as Henry-the-Fourth-like, Babinger’s next sentence would disabuse him: “When recognized and greeted… Mehmed would stab the interloper with his own hands.” Phrantzes is alleged to have remarked to the effect that Mehmed enjoyed killing men the way most men enjoy killing fleas.

Following Mehmed beyond the conquest of Constantinople, it becomes evident that he brought atrocity in his train, whether in Greece, Albania, Wallachia, or as far as Otranto in Italy, which he besieged in the winter-spring of 1480-81. Again, the behavior of Mehmed, who for Waltari is Mohammed, finds its model in the tradition of jihad going back to the campaigns of the Turk’s namesake. Waltari appears to be arguing that terror, like the latest in artillery or siege engines, is a technique in service of power and that Islam, perfectly embodied in the Sultan, is the first of the monstrous power-cults or ideologies. There is thus no contradiction when Angelos explains to his numerous interlocutors on numerous occasions that faith is entirely irrelevant to Mohammed, who acts on an anti-faith that seeks universal dominance and requires for the realization thereof the erasure — the total erasure — of every opposing tradition. All of the subsequent power-cults, including those of the Twentieth Century, would be the progeny, at however many removes, but nevertheless the progeny of the original power-cult. “Mohammed believes in power,” Angelos tells Anna; “for him there is neither right nor wrong, neither truth nor lies [and] he is ready to wade through blood if it suits his schemes.”

Grant, the German engineer in Constantine’s service, resembles Mohammed in having no relation to anything transcendent while being entirely concentrated on his praxis. Grant has made improvements in the antique military equipment of the defense, but he can increase its efficiency only so far and he openly admires the technical innovations being deployed by the other side. Grant has sought access to ancient documents by Pythagoras and Archimedes said to be held in the Imperial Library, but the librarian has rebuffed him. Grant explains his curiosity to Angelos: “Archimedes and Pythagoras could have built engines to change the world. Those old fellows knew the art of making water and steam do the work of men; but no one wanted such things in their day, and they never troubled to develop them.” Grant cannot fathom why the philosophers “deemed the supernatural world more worthy than the tangible.” As he sees it, “knowledge of heavenly things has no practical value.” Angelos believes that Grant has committed himself to the wrong side and says as much, but Grant remains unperturbed. The sultan hardly needs Grant, of course, as he already has Orban and his great guns. Praxis for its own sake is another kind of anti-faith, as dehumanizing in its trend as the Sultan’s power cult.

What opposes itself to these dehumanizing forces? A mere two-millennium tradition is the answer, from which, as the shadow of conquest looms, those who should honor it defect. Angelos learns from Anna that her father and thirty others — who also prefer the turban to the miter — have stealthily made it known to Mohammed that, on his word to spare them, and with the emperor dead or deposed, they shall step forward as a vassal government to rule in the Sultan’s name. Anna, speaking for the Megadux, says: “We are not delivering ourselves into [the Sultan’s] hands; on the contrary, his political sense will tell him that this solution is the best one for himself.” When the Turks at last take the city, the folly of the treacherous scheme sees itself played out. Here Waltari adheres closely to what is known from the accounts of Phrantzes and Ducas. After three days of rapine and plunder, Mohammed decreed a return to discipline. He commanded that Notaras come to him. Notaras indeed came. Mohammed asked him for the names of those other parties to his conspiracy and gave the appearance of favoring it. The next day, the conqueror summoned Notaras and his confederates to appear in public. Waltari narrates the sequel this way:

Mohammed nodded haughtily and said, “Let your own people then be your witnesses. Do you promise and swear by your God and all your saints, and are you ready to kiss your cross in token of your submission and in confirmation of your oath, that you are willing to serve me faithfully unto death, however high the position to which you rise?”

The prisoners shouted and made the sign of the cross, plainly showing their willingness to confirm their oath. Only a few stood silent, regarding the Sultan attentively.

“So be it,” said Mohammed. “You have chosen. Kneel in turn, and stretch forth your necks, so that executioner may behead you all. In that way you will serve me best and most faithfully, and your heads I will raise up on a pillar beside those of your brave compatriots. And in this I am not dealing unfairly with you, since you have just sworn to obey my commands, whatever they may be.”

IV. Dark Angel commemorates the Fall of Constantinople as a tragic enormity insufficiently honored by the present, and as an event, in its author’s assessment, that forms the epoch between the Classical World in its medieval extenuation, and the modern world. Angelos’ descriptions of Constantinople convey the sad dilapidation of what had once been the largest and most brilliant city in the world; but these same descriptions also insist on the genuine continuity linking Constantine’s polis with the foundations of Rome in Seventh-Century BC Italy. Constantinople was in the Fifteenth Century a hybrid culture, partly Christian and partly Pagan — in other words, inhuman Islam’s humane antithesis. Byzantium had preserved Classical civilization more integrally than any other agency, including the western monasteries. Greek refugees from the conquest, arriving in Venice and Florence, contributed mightily to the Renaissance, but it should be kept in mind that the famous Rebirth of Greco-Roman art and literature nourished itself on a bloody death in the East. Insofar as the West today still refreshes itself on the Classical heritage, it owes a debt to the Eastern Roman Empire, whose last important redoubt fell to the jihad some five hundred and sixty-four years ago.

The cases of Waltari and those other writers whom I mentioned at the beginning of this essay also serve to remind us that a few decades ago, in the aftermath of World War II and in the onset of the Cold War, major writers and leading intellectuals of the West earnestly upheld an explicitly European civilization with ancient and medieval roots; many of those, like Waltari himself, leaned politically to the right, defending Christianity on the one hand while criticizing Communism and totalitarianism on the other. Most of Waltari’s novels appeared in English translation. Second-hand copies are still to be had, often cheaply, through the Internet. I strongly recommend Dark Angel and The Egyptian, but every Waltari novel in my experience is a good read. I also recommend the novels of Lagerkvist, a Swede, and Hansen, a Dane.

I know these writers because in the 1970s when I was an undergraduate studying Danish, Norwegian, and Swedish at UCLA, their books figured prominently in the curriculum. The professors presented them as serious and important. I learned some time ago that the Scandinavian Section of the Department of Germanic Languages at UCLA had been dissolved. Western institutions are purging themselves of historical memory while they fill themselves with resentment and hatred against the civilized soil in which they grew. A people conscious of itself must learn how to act — and especially how to educate itself — outside the institutions.

Thomas F. Bertonneau has been a college English professor since the late 1980s, with some side-bars as a Scholar in residence at the Russell Kirk Center for Cultural Renewal, as a Henri Salvatori Fellow at the Heritage Foundation, and as the first Executive Director of the Association of Literary Scholars and Critics. He has been a visiting assistant professor at SUNY Oswego since the fall of 2001. He is the author of over a hundred scholarly articles and two books,Declining Standards at Michigan Public Universities (1996) and The Truth Is Out There: Christian Faith and the Classics of TV Science Fiction (2006). He is a contributor to The Orthosphere and the People of Shambhala website, and a regular commentator at Laura Wood’s Thinking Housewife Website. For his previous essays, see the Thomas Bertonneau Archives.

I wished I could. We are depicted. Cowardice and treason of our roots.

“The Wanderer” is available on Kindle btw.

The Wanderer was Waltari’s first novel, as I recall. It belongs to the late 1930s or the very early 1940s. In the 1920s he had made an impression as a lyric poet and later as a journalist. His father, not incidentally was a Lutheran minister in the Finnish State Church.

The U.S. version is here, with our code:

http://amzn.to/2tXqdGv

THere are 3 other Kindle titles by this author shown at the bottom of that page…most interesting to me is “The Etruscan” since I know so little about the era.

I wouldn’t want to spoil it for you, but it’s well worth the time that you’ll invest in reading it.

It’s just an intuition, Dymphna, but I strongly suspect that you would respond positively to Lagerkvist’s Sybil.

I certainly enjoyed Sigrid Undset’s trilogy, Kristin Lavransdatter. The descriptions of family and community life, the wonderful landscapes…compelling.

Undset managed to create a strong female character without any of the usual feminist cant attached.

http://amzn.to/2sFkUrr

But I’m more curious to explore some of the other books you mention in your essay on Girard. My theology/philosophy professors were French Americans and they introduced me to Gabriel Marcel (plus others, e.g., Mircea Eliade). Marcel remains my favorite of the French existentialists though he denied being one, saying his own work was “concrete”. His thoroughly redemptive view of human life was/is sublime – though unblinking. He made Sartre sound adolescent. [There are some Marcel societies in the U.S.]

Your intuition concerning Marcel is a good one. Marcel was a philosopher, playwright, and story writer. He, too, is nowadays mostly a forgotten person.

Marcel was also a music critic…

Believe it or not, he’s not entirely forgotten, e.g.,

http://www.neumann.edu/MarcelStudies/

It’s a small Franciscan college.

My favorite of his works is “Creative Fidelity”, here:

http://amzn.to/2v3QmQZ

There is also a title still in print, “Music and Society”…for music majors, no doubt.

Marquette University still offers his work for study.

Certainly the prevailing modern situation finds its image in Waltari’s novel. Perhaps that is what you mean by “we.” Most startlingly, Waltari understood that it is a tendency of Late Christian societies almost entirely to misunderstand, or simply not at all to comprehend, their enemies.

Thank you for your comment.

Surely, almost all commenting on GoV are enraged at the “tendency of late Christian societies to misunderstand, or simply not at all to comprehend (or even to identify) their enemies”.

I don’t understand why you find it ‘startling’ that Waltari did, after all there have always been people who divined a given situation correctly.

Well, they tend to emphasize the jews rather than the real enemies. Time and again, same pattern.

Exactly.

P.s. Zack, for the time being it’s the Russians in the crosshairs; as you know, it’s always someone else, never that protected species–islam.

I find it startling – and so should you – because in 1952 Islam was not an issue. Islam was quiescent. The Foe was Communism, mainly in the form of the Soviet Union and its European client-states.

Thank you for your comment.

Point taken Thomas, and thanks for answering. I’m presently reading the on-line book. I’m not usually into historical novels–fascinating!

What you say is true, but maybe five years ago I remember reading a piece on the internet saying that the Arab states had been working on introducing a pro-Islamic view into the U.S. education system since the 1920’s, mainly through funding departments of Islamic Studies in Universities. My first reaction was skeptical, then I remembered myself as a junior in high school, while waiting for someone in a classroom, reading an unassigned chapter in our World History textbook. It explained to me that the Song of Roland should be banned from being taught in schools since it gave an unfavorable picture of Islam. I had read a bowlderized version of the same, and understood that it was an example of the medeivel “geste”, part of my heritage, and remember being shocked at the suggestion. The textbook was in its second or third year of use, and the year that I read that passage was 1958. Obviously, this intellectual aggression was already well underway at that time, even though the main enemy was perceived to be Communism, and Waltari obviously picked up on it. My own recognition of Islam as a serious potential and actual enemy did not begin until the fall of the Shah of Iran, plus the discovery of Mohamed and Charlemagne on a second hand book rack.

“Surely, almost all commenting on GoV are enraged at the “tendency of late Christian societies to misunderstand, or simply not at all to comprehend (or even to identify) their enemies”.

Don’t call me, Shirley.

With that trivial (but persistently hilarious) issue aside, I’m damned “enraged” and supremely glad that you (amongst so many others) grasp just how destructive Euro “virtue signalling” has become as a source and wellspring of aimless and “supposed” condemnation against logical and rational Western minds.

Take that as you will.

“Most startlingly, Waltari understood that it is a tendency of Late Christian societies almost entirely to misunderstand, or simply not at all to comprehend, their enemies.”

What would you (or Waltari) attribute this to?

My own guess is that Late Christian groups have lost sight of the more ancient Church Militant and—taking the (reformed) charismatic aspect of their doctrine a bit too seriously—casually slid from its relatively newfound, post-industrial-revolution prosperity over into an unmerited (i.e., “bleeding heart”) pity for less-advantaged peoples.

Too often, this seems to have been done, regardless of how deserving those (typically) Third World cultures were of their self-imposed poverty and destitution. Insert post-colonialist guilt syndrome >here<.

Thus we saw long-standing traditions of "turn the other cheek" and The Golden Rule morphed into blood drives for terrorist "Palestinians" and, finally, the deranged willkommenskultur with its suicidal virtue signalling catchphrase of, “we have so much while they have so little”.

Perhaps, most conspicuous or telling of all, is how the Visegrad Four (Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia)—each of whom is far too well-acquainted with ideological domination and submission—have given such short shrift to the EU’s plaintiff and now-threatening utterances about accepting their “fair share” of criminal, predatory, rapist “economic tourists”.

So, is there any basis for recognizing some sort of pattern involving Late Christian societies and this bizarre trait of voluntarily opening their veins for the sake of those who—without further prompting—would just as readily open those same (infidel) blood vessels for all involved?

For some insight into the underlying basis for your comments, I highly recommend Bertonneau’s earlier essay on GoV, about Rene Girard. He explains – from 1848 onward – the growing roots of envy/desire and resentment. In modern terms, located now in current obsessions about privilege – e.g., feminism, Black Lives Matter More, etc.

He also shows how our administrative bureaucratic states (all mini-me soviets) feed this soul-killing dysphoria…

Particularly of interest is his fisking of Rousseau, Nietzsche, et al, on down to the modern day flim-flam of the deconstructionists…

Be sure to read what he says about cell phone addicts…

Look on the top bar of our home page for authors.

Very schematically, I believe that successful societies are in the long-term their own worst enemies, especially when they are ostentatious about their success. The founders of any society have a near-impossible task; the builders of the society also have an onerous, Herculean task. The inheritors of the founders and builders have an easy time. Easiness begets complacency, complacency begets ignorance, and ignorance begets folly.

You’re looking to psychological and philosophical issues as explanations for the decline of Western cultures. I prefer a structural and genetic explanation.

Structurally, a successful civilization and government tends to dismantle the conditions of its own success. Commercially, power and wealth goes to a money-lender and land-owner (bankers) class. This puts the original population into debt and deprives them on their land and heritage. The commercial success and government-protected lanes of communication guarantees that the cheapest foreign products will displace the native artisans, farmers, and merchants. The government itself expands and centralizes control, requiring ever-higher taxes to maintain its existence.

Law of Civilization and Decay

The peasants and villages who normally pass along the culture, not to mention the religion, are displaced and forced to become beggars (welfare-recipients) in the cities. The cities become the centers of cultural and economic activity, but do not either the cultural identity or the martial prowess of the original peasant and villager stock.

The displacement from their own lands brings the birthrate down radically. This was illustrated in countries from the Byzantine Empire up to the present.

Genetically, (this is my speculation) bringing in cheap foreign goods, dispossessing the peasantry, and providing general handouts, from the bread and circuses of the Roman Empire to the welfare state of today, destroyed the natural selection processes selecting for what we see as virtues, and allowed the genetic deterioration of the population. The points of weakness this exposed was both the birthrate, and the general readiness of the populace to defend their country, including their actual intellectual quality and their possession of public virtue which allowed a unified response to danger.

Does Waltari discuss the frenzied destruction of icons (ikons) among the Orthodox in an attempt to appease what they saw as a God angry about idolatrous images? The first iconoclasts (at least among Christians).

Dear Dymphna:

No — he does not. The topic is nevertheless a relevant one. The Iconoclastic wave in the Eastern Roman Empire (Byzantium) coincides with the initial wave of Islam. Not incidentally, an early focus of Iconoclasm was the Cult of the Virgin. Not incidentally, Christian Iconoclasm has its probable source in Syriac Christianity (in the writings of John of Damascus), which tended towards puritanism. Not incidentally, Syriac Christianity has been cited as a probable source of Islam. Nevertheless, Iconoclasm did not prevail in the Orthodox World, as the glory of any Orthodox Church will attest.

We might recall that Deuteronomic Judaism, another probable source of Islam, is also iconoclastic.

Thank you for your comment.

Sincerely,

Tom

Courtesy of the Digital Library of India (and the priceless Archive.org):

https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.148197

Thank you!

Thank you.

Link to Egyptian…bottom link

If The Bible is taken seriously, then a true christian empire cannot fall. It took a while, but just as the israelites of old, so also have the greeks fallen to the forgotteness of God.

The Church Metaphysical cannot fall. But the worldly incarnation of the Church is subject to all the tendencies of mortality. As an institution, it can corrupt itself. A Catholic, I point to the existing Catholic Church.

As a Christian, I believe that the true Church of Jesus Christ cannot fall. You can kill a dozen apostles, but hundreds will raise in their stead – given they do it “by the book” and die willingly for the glory of God.

Human systems – however – can, and will fail and fall – no matter what you name them – for example The Holy and Ultimate Authority on what Jesus Said – or something.

I am not a catholic, but I can see that the devil has performed the only possible attack against the Christian Empires of Europe and Americas: He seduced them through lust for life, women, fun, entertainment, and so on.

There is nothing wrong with “music” by itself. Its when you make it the goal and reason for life – that is when fun gets life threatning.

Thank you, Thomas Bertonneau, for not only a masterful, informative review and precis, but for involving yourself in the comments section.

I was able to download both the Egyptian and Dark Angel in pdf form. The links are available to readers elsewhere on the comment track.

It’s difficult for me to forget the first sacking of Constantinople and the breaching of its defenses came in 1205, at the hands of the crusaders, who were not terribly scrupulous about what city or territory they sacked as long as it contained wealth they could steal. It’s not surprising that Constantinople never received any aid from Western kingdoms or from the Catholic Church.

I was struck by your description of how the Turkish forces used modern technology, while Constantinople put a new paint job on ancient defense structures. People today make the same mistake, assuming the backwardness of Islam with respect to scientific investigation, literary accomplishment, and liberality in government means that Islam can’t and won’t use the most sophisticated politics and technology available to carry out jihad. This is a case of badly underestimating your opponent.

Underestimating the ability of Islam to overrun Western countries and institutions may be part of the reason people are willing to put up with political leaders who are openly surrendering the sovereignty of their countries. You can see it in lots of comments on these pages, where people often write that once Westerners get fed up, they’ll ship the Muslims back to their own countries.

The review was ambiguous on this question, but once the siege was in place, did the dissensions and intrigues of Notaras make a difference? Would Constantinople have had a chance to withstand the siege, even if not torn apart by religious fanaticism and power intrigues?

The Fourth Crusade was a disaster, but it was not a pattern, as the original Mohammed’s campaigns were for jihad.

The current battalion of jihadists employs what modern militarists regard as primitive front-line weapons, such as the suicide belt or the pressure-cooker shrapnel bomb. Behind the scenes and in preparation, however, the soldiers of jihad are extremely adept at exploiting digital communication technology.

Waltari saw this, fifty years before the advent of the cell phone.

Thank you for your comment.

One of our readers from Brazil found an online version of Dark Angel

https://archive.org/stream/in.ernet.dli.2015.148197/2015.148197.The-Dark-Angel#page/n7/mode/2up/search/Dark+Angel+Mika+Waltari

use the root – archive.org – to go through the registering rigamarole and then put in the name of the book you want. You will have to work on font size unless you’re far-sighted.

I gave it a try in audiobooks.There are at least 5 books by this author in audio format.

Thank you.

I confess to owning and a Kindle, but I also have an enormous in-house library of actual books. Actual copies of actual Waltari novels are easily available. I bought my copy of Dark Angel, with an original dust-cover, for under twenty dollars. Other copies, including paperback copies, can be had for a few cents plus the shipping charge.

“There is thus no contradiction when Angelos explains to his numerous interlocutors on numerous occasions that faith is entirely irrelevant to Mohammed, who acts on an anti-faith that seeks universal dominance and requires for the realization thereof the erasure — the total erasure — of every opposing tradition.”

Coexist, anyone? Not so much.

What a curious find. The Egyptian was one of my father’s favourite books and he recommended it highly to me when I was a teenager. Of course I didn’t understand back then why it was so special. And forgot about it since… which shall be undone. Two more for the wishlist!

“But don’t misunderstand me… if he is a man, then he is the new man — the first of his kind. With him begins a new era… which will bring forth men very different from the race we know.” Such men will be “rulers of earth, rulers of night, who in their defiance and arrogance reject heaven and choose the world.” According to Angelos, these men “will bring the heat and cold of hell to the earth’s surface,” and “when they have subjugated land and sea they will build themselves wings in their demented lust for knowledge, that they may fly to the stars and subjugate even them.”

The common thread that links Islam with Marxism, Liberalism, Environmentalism and Space Exploration. The linkage of the character if Islam with the other groups promise a fascist future of ruthless competition among these groups which will result in a misery hitherto unknown to humans. Ray Bradbury’s “The Martian Chronicles” portrayed the conquistador spirit of the space explorers that was significantly toned down for the movie. Thank you but I prefer the Millennium in which Christ’s rule will bring order out of the presently impending chaos.

Interesting, your last linking, that of space exploration…Amazon’s Bezos wants to start up his own group. The megalomania is off-putting

When Christianity becomes a customary part of people’s lives, it begins to lose strength, because to be a good Christian or a good Jew takes a lot of effort, as Dietrich Bohnhoeffer warned. One has to internalize the moral law and live accordingly, as an individual – not outsource one’s morality to a PC ideology which gives us permission to hate on behalf of self-appointed victims.

Psychiatry made morality very unfashionable. The church has disgraced itself with the sexual abuse and sexual orgy scandals, even at the Vatican level. Faith in Rationalism from the 18th century made us arrogant, and now even that has been thrown over board. People prefer self-indulgence. (Gender is no longer determined by rational scientific genetic inheritance but what we feel we are! Ditto with the global warming scam.)

Civilization depends on individual morality. The Left has undermined both individual responsibility and the Judeo-Christian moral law. Unless both can be restored, we’re finished and we’ll end up like the Germans who turned a blind eye to Hitler.

Except, instead of the State slaughtering the Muslims, as Hitler slaughtered the Jews, it will be the Muslims, with their cultural IQ hovering between minus 1,000 and zero, who are already doing the killing, raping, raiding, pillaging and every criminal gangster activity known to mankind.

Speaking of a novel, does anybody know if that French new one has been translated into English by now? I don’t remember the name, but it was mentioned in a post on this website.

Submission – by Houellebecq. I believe it has been translated.

Thank you, unfortunately that is not the one (though I might give it a try too). The one I’m talking about got published last year and was more about a violent overthrow, rather than a democratic change.

After some googling I found out it’s the book Guerilla by Laurent Obertone and, unsurprisingly, it hasn’t been translated since.

If someone has more information about whether or not it’s avaible in English (or even German) somewhere, please let me know!

The Egyptian is one of my two favorite books of all times, since I was in the elementary school and listened to it on the radio everyday at 2 pm. This story, which was being told by Sinuhe the Egyptian from his exile, always started with this lines, that I consider the most beautiful explanation of patriotism: “He, who once tasted Nile’s water, will always miss Nile. His thirst won’t be quenched by any other water.” (citing from memory, from Polish). The Egyptian was the reason I also read the Dark Angel and it was very painful reading. Thank you, for reminding us of those books.

Thank you for your comment. The Michael Curtiz film of The Egyptian from 1954 rather surprisingly succeeds in translating the lyrical quality of Waltari’s prose to the Technicolor Big Screen. The film is almost as serious as the novel — and Curtiz’s direction is intelligent throughout. (Curtiz is most famous for Casablanca and a year after directing Edmund Purdom, Jean Simmons, and Peter Ustinov in The Egyptian, he directed Elvis Presley in King Creole!) Regrettably, the studio has never released The Egyptian in high quality format. I own a DVD from a Korean source that is simply a transfer from a worn-out VHS tape. Even in that form, however, the film is worth watching.

A poor quality version of the film may be seen in full on YouTube

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LI3JMxWE-Qo

Just finished reading The Dark Angel on line. Yes, painful and dark. If I wasn’t conversant with Greek tragedies before, I certainly am now.

The book is also available here: https://ia801609.us.archive.org/27/items/in.ernet.dli.2015.148197/2015.148197.The-Dark-Angel.pdf

Audible has The Dark Angel as an audiobook: https://www.audible.com/pd/Classics/The-Dark-Angel-Audiobook/B00JXQWNM0/ref=a_search_c4_1_3_srTtl?qid=1509805402&sr=1-3