Many thanks to LN for translating this essay from Invandring och mörkläggning:

Sunday Chronicle: If you want to change people’s minds, you have to talk to their elephants

by Karl-Olov Arnstberg

August 7, 2022The American psychologist Jonathan Haidt is one of the most interesting thinkers of our time. This year, the publisher Fri Tanke has published in Swedish his 400-page popular science study of morality: The Righteous Mind.

One question that Haidt twists and turns is how we make decisions and act. He notes that most people distinguish between reason and emotion. This goes back to the Greek philosophers. They put reason first and despised emotionally driven people. A man who controls his emotions will live a life of reason and justice and can expect to be reborn in an otherworldly heaven of eternal bliss, while the man who fails to control his emotions will be reincarnated as a woman — at least if Plato is to be believed.

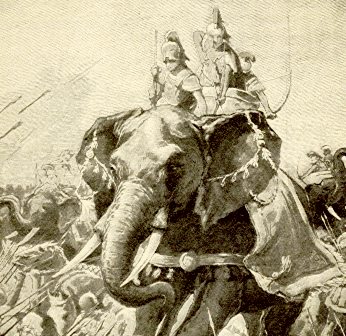

Haidt likes metaphors and describes the divided mind as a rider on an elephant. He chose an elephant instead of a horse because elephants are so much bigger and smarter than horses. The rider is your reason and for most of us it seems that reason rules. Or, at least that’s the desirable thing. When we can’t think, emotions rule. Some people are good at keeping their emotions in check and making rational decisions. Others give in to their emotions and things can go either way.

In Haidt’s metaphor of thinking, the elephant is in charge, although he or she may be open to the rider’s persuasion. The rider is very small and the elephant is very big. The task of the rider is to serve the elephant. Haidt writes:

The rider is our conscious reasoning — the streams of words and images of which we are fully aware. The elephant is the other 99 percent of our mental processes — the ones that happen without our being aware of them but that actually control most of our behavior. The rider and the elephant work together, sometimes less effectively, as we stumble through life in search of meaning and coherence.

Automatic processes govern the human brain, just as they have governed animal brains for 500 million years. When humans developed the capacity for language and reasoning sometime in the last one million years, the brain did not reprogram itself to hand over the reins to a new, inexperienced driver. Rather, the rider was brought in because it added something that the elephant could use. Haidt writes:

The thinking system is not equipped to govern — it simply doesn’t have the power to make things happen — but it can be useful as an advisor. The rider is an attentive servant, always trying to predict the elephant’s next move. If the elephant leans the slightest bit to the left, as if preparing to take a step, the rider looks to the left and begins preparing to assist the elephant in its next leftward movement. The rider then loses interest in everything that is happening on the right side.

The elephant needs the rider, among other reasons, to be able to see further into the future, to see the consequences of the elephant’s actions. In this way it can help the elephant make better decisions in the present. It can learn new skills and master new techniques, which can be used to help the elephant achieve its goals and avoid disasters. And, most importantly, the rider acts as a mouthpiece for the elephant, even if that doesn’t necessarily mean he or she knows what the elephant is really thinking. The rider constructs after-the-fact explanations for everything the elephant has come up with.

Here Haidt adds another metaphor. Now the elephant is a politician and the rider is his full-time press secretary whose job is to present the politician’s views and actions in a positive way, but also to defend the politician. However, the press secretary is not receptive to arguments. Something you will never hear is “Well, you’ve got a point there! Maybe we should reconsider this decision.” A press secretary does not have the power to make or review policy decisions.

The intelligence quotient (IQ) is by far the most important variable in how well people argue. Smart people can be very good press secretaries, but they are no better than others at coming up with arguments for the opposing side. People use their intelligence to support their own arguments rather than to explore the whole issue more fully and impartially.

Returning to the elephant and the rider, the rider is good at finding reasons to justify what the elephant is going to do next. Once humans developed language and started using it to gossip about each other, it became extremely valuable for the elephants to carry around a sort of full-time PR firm on their backs. Haidt writes:

You can see how the rider serves the elephant when people become morally numb. They have strong gut feelings about what is right and wrong, and they constantly struggle to create after-the-fact constructions that justify the feelings. Even if the servant (reasoning) returns empty-handed, its master (intuition) does not change his mind.

What guides the elephant are intuitions, inherited and experiential cognitions. They do not consist of reasoning that leads to a decision. We all make our initial judgments in a flash. Less than a second after seeing, hearing or meeting another human being, the elephant has already begun to lean towards or away from that person, and that leaning influences what it thinks and does next. Intuition comes first. The elephant listens to the rider, but only if the rider says something that the elephant wants to hear. Otherwise, the elephant turns a deaf ear.

Reason is the servant of intuition. Decisions are made by both animals and humans in the same way, by intuition. The constant question for the elephant on its journey through life is how to relate to the information it receives about life from its senses and from the rider. Should it be positive, which Haidt describes as leaning a little closer, or should it be negative and dismissive; that is, leaning away.

Haidt’s metaphorical description of what happens when we feel, reason and make decisions has great explanatory value for those who want to know what happens when people hold on to or change their minds. Imagine a parliamentary debate in which a number of politicians are arguing against each other. There is no chance that any of them will change their minds. The elephants lean away from their opponents and the riders make frantic efforts to refute their opponents’ claims. There is, however, little chance that those of us watching the debate on our television sets will change our minds. A tiny, tiny chance, because here too the elephants are in charge and we do not listen without prejudice. We are adept at finding fault with other people’s opinions but poor at accepting arguments that challenge our own positions.

Haidt writes that we all have confirmation bias, the tendency to seek out and interpret new evidence to confirm what we already hold to be true. People are fairly good at challenging claims that others make, but if it’s your belief, it feels like your property — almost like your child — and you want to protect it, not challenge it and risk losing it.

The chances increase if we discuss the issue with our friends, or if we listen to a debate among a number of friends. Then we are positive. If they are friends whom we respect and admire, then of course the chances are even greater. The elephant rarely changes direction as a result of objections from its own rider, but it can sometimes be guided by the mere presence of friendly elephants, or by good arguments given to it by the riders of the friendly elephants. The elephants are in charge, but they are neither stupid nor despotic. Haidt writes:

But friends can do what we cannot do ourselves: they can challenge us, give reasons and arguments that sometimes trigger new intuitions and thus enable us to change our minds. Sometimes we do this when we ourselves are mulling over a problem — when we suddenly see things in a new light or from a new perspective. Most of us don’t change our minds on a moral issue every day or even every month completely without pressure from others.

Haidt calls riders who are skilled at talking to elephants elephant whisperers, and singles out both former President Bill Clinton and the author Dale Carnegie as skilled elephant whisperers. In his famous book How to Win Friends and Influence People, Carnegie repeatedly urged readers to avoid direct confrontation. Instead, he advised them to “start out friendly,” to “smile,” to “be a good listener” and to “never say ‘you’re wrong.’” The persuader’s aim should be to express respect, warmth and an openness to dialogue before putting forward his or her own point of view. Haidt writes:

It is such an obvious thing, yet few apply it in their moral and political reasoning, because our righteous minds so easily connect the dots. The rider and the elephant work seamlessly together to fend off attacks and throw their own rhetorical grenades. The performance may impress our friends and show our allies that we are loyal team members, but however watertight the logic, it will not change our opponents’ minds if they are also in combat mode. If you really want to change someone’s mind on a moral or political issue, you need to see things from both that person’s point of view and your own. And if you really see it the other person’s way — deeply and intuitively — you may even feel your own opinion change. Empathy is the antidote of righteousness, although it is very difficult to feel empathy if the moral divide is wide.

— Karl-Olov Arnstberg

With all due “respect, warmth, and an openness to dialogue”:

Both my elephant and I were attentively listening, up until the point when we heard the author whisper wonders about the superhuman abilities of Bill Clinton, that we should humbly emulate [and submit to]. As the article itself explains: “it is very difficult to feel empathy if the moral divide is wide”.

After all, Billy the Chief Sociopath is a key conman of the global predatory overclass that is waging war on us. In other words, the “moral divide” of the Parasitic Divergence is indeed wide. It means that the predatory overclass (that Our New Spritual Master, Billy belongs to) has become a whole separate society, even with a separate infrastructure, that clearly regards itself nothing less than a superior species. And they are doing everything in their might to hold us down and prevent us from becoming as “successful” (powerful) as they are.

This is exactly the essence of the ongoing war the top globalists, including Billy, are waging on the rest of the people they consider inferior — to the point that prominent members of the (not so) secret societies of the London City literally call us little people “livestock”.

Yet I am supposed to “start out friendly,” to “smile,” to “be a good listener” and to “never say ‘you’re wrong'”, and I am expected to “express respect, warmth and an openness to dialogue before putting forward my own point of view” — as Killy Billy tells me to do, right from the Oral Office.

I am supposed to become a sheeple, in fact.

This article is very deceptive stuff, hyper-Marxist chicanery, and anti-freedom of speech.

So my answer is “NO”. I will not submit to this manipulative piece of covert speech-dictates camouflaged as a personality improvement course about agreeableness.

I mean ‘c’mon man’!!! Leave MY elephant alone! (And I am not smiling.)

Best Regards,

with all the due respect again, sending loads of manipulative fake smiles and huge clouds of woke rainbow fuming out of Bill Clinton’s saxophone in Epstein’s Island of True Dialog (where we shall all meet in peace and harmony one day, riding on the backs of our gene-edited elephants [in the room]).

OK. I did some research about the man, Jonathan Haidt, who has had the audacity to set top psycho globalist Bill Clinton as an exemplary human being concerning decent behavior. Spoiler: I came to the conclusion that Haidt is a planted conman who subversively attacks the First Amendment and support s globalist tyranny vs. freedom.

I will analize three articles of the Atlantic — Mr. Haidt wrote two of them and he quotes and refers to the third one, to support his arguments:

__________________________________

Here we go: Haidt is writing about the “polarizing effect” of social media, and the “far right”:

https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2022/07/social-media-harm-facebook-meta-response/670975/

“At a far higher level of conflict, the congressional hearings about the January 6 insurrection show us how Donald Trump’s tweets summoned the mob to Washington and aimed it at the vice president. Far-right groups then used a variety of platforms to coordinate and carry out the attack.”

— I beg your pardon?!

https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2022/07/social-media-harm-facebook-meta-response/670975/

— He also seems to protect the oppressive globalist machinery, thus supporting the declared authoritarian agenda to brand free people who speak freely as “terrorists”. Read it carefully:

“Or consider the the far right’s penchant for using social media to publicize the names and photographs of largely unknown local election officials, health officials, and school-board members who refuse to bow to political pressure, and who are then subjected to waves of vitriol, including threats of violence to themselves and their children, simply for doing their jobs. These phenomena, now common to the culture, could not have happened before the advent of hyper-viral social media in 2009.”, Haidt writes.

— Oh, those snowflake Corona Enforcers who were allegedly “subjected to waves of vitriol”, including alleged “threats of violence”.

Notice, that at the same time Haidt literally boasts with standing up to the snowflake culture in the schools. But concerning the Plandemic, he supports the same woke phenomenon. Strange…

One must point out, that Haidt deliberately mixes up certain behaviors that are against the law, with some others that do not violate any laws. For example making threats of violence is clearly against the law, but “vitriol” is absolutely not. t creates the false impression that online “vitriol” (whatever it is) is something that must be punished.

Which goes to show, that Jonathan Haidt ATTEMPTS TO SUBVERT THE FIRST AMENDMENT by fake arguments that are based on pseudo-science and pseudo-morality; and he pushes the general public opinion towards the left, thereby subverting the norms of the Old Normal.

Also, the unspoken implication he makes here, I think, is that social media should be regulated more. The bottom line is that he never challenges the legitimacy of globalist-owned “social media” (FB and TWTR) — he just “argues” with them about some pseudo-science, thereby actually legitimizing them. Even Mark Zuckerber seems to have engaged in an online debate about some issues Haidt addresses, mind you. This is a privilege that goes to show that Haidt is in fact controlled opposition. Will the alternative media ever get such attention from Zucki?

https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2022/07/social-media-harm-facebook-meta-response/670975/

And what “political pressure” is he talking about? It is nothing else but the pressure of FREEDOM, my “far-right” friends. The pressure of freedom that makes people protect it when they are subjected to medical tyranny and election fraud.

https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2022/05/us-politics-threats-violence-harassment/629739/

The title of the Atlantic article is “The Great Rage”, which presents the righteous anger of innocent people under globalist assault, as if their “rage” had no cause. It frames the reaction to tyranny as something immoral, in a very insidious way: the point-of-view of the attacked is completely missing. This is clearly a psyhopathic method of annihilation, when the real victim’s grounds to self-defence are not even mentioned, but are handled as non-existent. And the abusers (the globalists) are turned into the victims. Which comfortably justifies police brutality in Canada, The Netherland, Australiia and elsewhere.

What Haidt refers to in the above paragraph is actually another article in the Atlantic he linked in, that is whining about alleged “threats” against pandemic enforcers and election fraud enablers:

“According to The New York Times, more than 500 top health officials have quit their job since the beginning of the pandemic, many of whom cited threats and intimidation as a decisive factor. One 2021 survey by the publication Education Week found that 60 percent of principals and school administrators said that their employees had been threatened within the past year over the schools’ handling of the coronavirus crisis. And increased violence, or the threat of violence, has also spread to areas of life that might not usually be inflected by politics. The Federal Aviation Administration tallied almost 6,000 reports of “unruly passengers” in 2021, compared with fewer than 150 in 2019.”

— So actually Haidt indirectly quotes the New York Times, the house blog of George Soros Inc., that runs a piece about how the poor enforcers of the plandemic have been threatened during the fake “coronavirus crisis” by “unruly” people.

Once again: “UNRULY” people. These words most probably refer to free people who refused to submit to authority for the sake of submitting to authority when they taveled by air.

The statist bruhaha Haidt refers to as something valuable goes on like this:

“In one sense, the everyday nature of the violence and harassment that have become so prevalent is part of what makes this dynamic so concerning. Trust in government has suffered a sharp decline over the past 50 years, but a study by the Pew Research Center also found that Americans have lost further trust in other public institutions over the course of the pandemic. One solution for these ills is to encourage greater participation in civic life by idealistic Amerians who want to do good. But such encouragement can’t help but be undercut by the new norm that people working in a public-facing job, or in any role that might excite public interest, can expect a potential torrent of abuse at any minute. Many—though not all—stories of health officials, election workers, and school-board members inundated with threats end with the person at the center of the storm stepping back from their work in search of some measure of anonymity. Public service, in their view, is no longer worth it.”

— My conclusion: for all intents and purposes Jonathan Haidt is a globalist plant that pretends to care about free speech. But in reality it promotes globalist oppression by increasing the noise level, in order to disturb the natural forces of the society that could come to an agreement in the face of tyranny.

Doing this, he actually furthers the marxist agenda as well — while clamimng that he opposes it.

All in all, Mr. Haidt is acting at the same hellishly low moral levels as Mr. Clinton he tells us we should emulate. Yet Haidt is the one that vindicates the right for himself to address and judge the “morality” of others, all in the name of science [scientism].

So Mr. Haidt is a very disgusting globalist narrative-shaper.

Now, I have no time to research further, whether Haidt has just managed to deceive Karl-Olov Arnstberg (who otherwise seems to genuinly oppose the NWO), or Mr. Arnstberg is a globalist plant of the same kind.

Nothing is what is seems nowadays.