The “refugee” crisis has thrown Europe into a turmoil over the past eighteen months. The big question now is: Which Western European nation will be the first to flip and turn completely against the policies of German Chancellor Merkel?

Sweden, of course, a lost cause. With the trial of Geert Wilders about to start in the Netherlands, the immediate political prospects of the PVV are being thrown into doubt. France is in chaos, and may turn to Marine Le Pen and the National Front as a result, but that election is still some months away.

So Austria may be the first to make the flip. If the rerun of the presidential election puts the FPÖ’s Norbert Hofer into office, the ocean liner of the Austrian state will continue its slow swing away from “Welcome Refugees!” towards “Build the Fence!”

Many thanks to JLH for translating this article from Neue Zürcher Zeitung:

From Openness to Separation

by Meret Baumann

September 6, 2016During the asylum crisis, Vienna executed a pirouette from a very liberal policy to a limit on refugees. That shook the people’s trust. Suddenly, dread made all the months of debate seem ludicrous. The ignoble squabble of the federal states over the acceptance of asylum seekers, for instance. Or the scandalous conditions in Traiskirchen refugee camp, where as many as 2,000 persons had to live in the open because of overcrowding. On August 27, 2015, the crisis was suddenly no longer in the Mediterranean or the Balkans, but right there in Austria, when 71 horrifyingly suffocated refugees were discovered in a side-tracked refrigerator car, because of the decomposition fluids leaking onto the tracks. People and politicians reacted with shock. Vigils took place in several cities, Cardinal Schönborn read a memorial mass and the famous “Pummerin” bell — only used on special occasions — was rung.

Applause and Emotion

The tragedy played almost no role in the decision by former Chancellor Werner Faymann to open Austria’s border for the refugees coming from Hungary, in a joint action with his colleague, Chancellor Angela Merkel, on September 5th. On that night, the two leaders had no real alternative. But it was a contributing factor to the scenes that played out in Nickelsdorf on the border and at the Westbahnhof in Vienna. The desire to help was enormous, the special trains from Hungary were greeted with applause, and even the Interior Minister Johanna Mikl-Leitner, known as the “iron lady,” was visibly moved at the western railroad station. “My heart trembles when I see this misery,” she said. And that these people were now safe.

Aid groups and volunteers impressively organized the pass-through of hundreds of thousands at that time. Austria acted as a stronghold of solidarity, and Chancellor Faymann was pleased to play the role of warm-hearted statesman, condemning the harshness of Eastern Europe. At any rate, the generosity was not too difficult. Most of the refugees were just going on to Germany. Austria was just the “snack stop on the folk migration,” as the well-known writer Sibylle Hamann put it.

It never came to a real change of mood in the population. Rather, we can assume that the skeptics of opening the border were already in the majority. But when pictures of Spielfeld appeared in the social networks multiplied a thousandfold at the end of October, showing a few soldiers watching helplessly as hundreds of immigrants overran the border, the loss of control became more than clear, and the critics could not be ignored. Besides, more and more asylum seekers wanted to stay in Austria in the late autumn.

Near the end of the year, this pressure brought on a drastic change of course and a political upheaval unsurpassed in this country already beset by crises. First, it was the conservative ruling partner, Austrian People’s Party (ÖVP), which changed its Foreign Minister’s course and vehemently demanded an end to the “Welcoming Culture.” Ultimately, in November, no other than Faymann, who had compared the measures of Prime Minister Viktor Orban to those of the Nazis, had to agree to the building of a fence on the Slovenian border — even though this step was primarily for the purpose of orderly entry, and its announcement teetered into the comic when Faymann called it a “little door with side portals.”

Vienna Presses Forward

There is now a 4-kilometer-plus fence on Austria’s southern border, smack in the middle of Schengen Europe. And then, to an extent, the dam broke. In January there followed the decision to limit asylum seekers to 37,500 for the present year and to increase the severity of the asylum law. At the end of February, Vienna coordinated the end of the Balkan route. That is why the number of asylum seekers has shrunk markedly and holding it to an upper limit is no longer out of the question. And yet, the government is on the point of adopting an emergency measure which — by de facto invalidation of the asylum law — is expected to allow the rejection of practically all applications at the border.

In spite of Brussels’ and Berlin’s criticism of Vienna’s unilateral steps, the closing of the Balkan route soon became the EU party line. With its pressing forward, Austria brought a new dynamic to the refugee debate, and made a decision that caused Merkel and the EU to cringe. To be sure, the price in political credibility is steep. The government’s about-face was above all a reversal of direction for the Socialist Party of Austria (SPÖ), which followed the lead of its coalition partner. This was an acid test for the party. For Faymann — the longest-serving European head of state after Merkel — it was the political end. At the beginning of May, he acceded to massive internal party pressure and resigned.

The two traditional partners, SPÖ and ÖVP had already sustained a historic setback in April, in the first round of the presidential election. The candidates of the two parties, which had shared the office since the founding of the republic, together achieved only 11% of the vote. In comparison, the Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ) had its best ever result with 35% for its candidate, Norbert Hofer. In the repeat election necessitated by judicial repeal, Hofer could become the first representative of a right populist party in Western Europe to hold the highest office in the land.

The FPÖ Has Been Gaining for Years

Not only the presidential election, but also the continuing high standing of the FPÖ in polls, show how great the loss of trust is, both in the populace, and between the two parties. The coalition has recently been shattered by its lack of unity, because a victory for the FPÖ is likely in the early elections. The government continues to implement the demands of the Freedom Party, without any reward in better polling results.

It would be wrong to see the crisis of the parties only in refugee policy. Indeed, as formulated by Fritz Plasser — a political scientist not given to hyperbole — Austria is undergoing an epochal upheaval. But the causes are above all the ideological chasms between the SPÖ and the ÖVP, expressed in a persistent incapacity for reform and a policy of patronage in both parties which is incomprehensible to large sections of the populace.

FPÖ, the “protest party,” has been profiting from this for thirty years. In that regard, it is not comparable to the Alternative for Germany (AfD). If the brief split of Frank Stronach and Jörg Haider and the Alliance for the Future of Austria (BZÖ) from the FPÖ (1) had not cost the Freedom Party votes, they would have been in first place three years ago in the parliamentary elections. Austria may yet experience that shock. The refugee crisis could prove to be the catalyst for that — no less, but no more.

Notes:

1. 2005

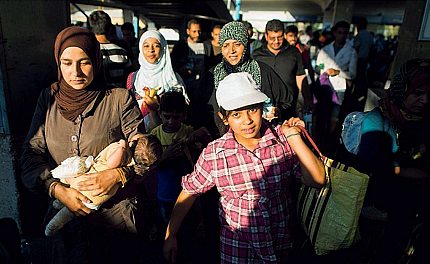

Photo: A year ago, official forces and volunteers funneled hundreds of thousands of immigrants through Austria.

Why are Germans so happy to commit culture suicide? Europeans are like lambs to the slaughter ! http://www.infowars.com/tv-ad-encourages-german-women-to-wear-hijabs/

Refugees? Police officers attacked by an african mob in the outskirts of Lisbon, Portugal.

Watch the video

http://www.cmjornal.pt/portugal/detalhe/agentes-da-psp-atacados-por-multidao