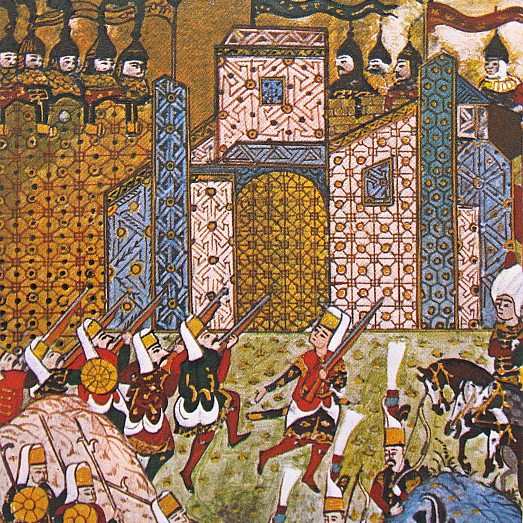

Seneca III takes up where he left off at the end of Part 1 of his account of the Siege of Rhodes in 1522.

The Cross and the Crescent: Rhodes, 1522

by Seneca III

Part II. The Appliance of Science.

Bombardment of the city began on the 29th of July. Although by September precise counter-battery fire had reduced Suleiman’s artillery to roughly half of its original strength the bombardment continued day and night, the cannon balls and primitive incendiary devices did not cease falling, and, since the middle of August, sections of the ramparts had begun to crumble under the weight of the fire.

Field sketch of the Fortress City of Rhodes as in 1522,

showing the initial deployment of the opposing forces

(S III, Rhodes, c 1978)

| Key: |

||||

| 1. | Post of France | 9. | Ayas Pasha | |

| 2. | Post of Germany | 10. | Ayas Pasha | |

| 3. | Post of Auvergne | 11. | Ahmed Pasha | |

| 4. | Post of Aragon | 12. | Qasim Pasha | |

| 5. | Post of England | 13. | Mustafa Pasha | |

| 6. | Post of Provence | 14. | Piri Pasha | |

| 7. | Post of Italy | 15. | Fort St. Nicholas | |

| 8. | Janissaries | 16. | Boom Defences |

|

However, whereas the concentration of firepower on a given point and the visible attrition of the fabric of the walls gave ample warning that an attack was imminent, a more sinister, less easily detectable assault was elsewhere deciding the fate of the city. There, beneath the walls in the dark almost airless tunnels and galleries burrowed by the Sultan’s miners the really crucial battle was shaping. Whereas a sustained, concentrated barrage gave ample warning of an impending attack, gunpowder mines could bring whole sections of the wall crashing down without warning, leaving the defences open to a human-wave assault from Suleiman’s troops waiting in trenches opposite the site of the breach.

Such a mine had been detonated on the afternoon of September 4th beneath the bastion of England, creating a ramp of rubble and a twelve-metre gap in the wall through which charged the waiting Turkish troops. It was a brutal engagement that lasted until evening. Courage and fortitude were commodities in ample supply on both sides, and both sides were led into battle by their respective commanders, De L’Isle Adam and Qasim Pasha. Eventually, climbing by then over a mound of their own dead and raked by fire from the Post of Aragon, the Turks lost the impetus of their thrust and were carried back by a wall of armour and broadswords.

Casualties on both sides were heavy, but on the side of St. John there were no replacements. Similar probing attacks took place with the same heavy casualties, and again preceded by mines, on the 9th against the Post of Provence, on the 11th again against England, on the 13th against Aragon and on the 14th once more against Provence. In effect mine warfare was deciding the fate of Rhodes, and it was here that the Grand Master’s farsighted preparations came to fruition through the activities and innovations of one remarkable man, a devout Italian by the name of Gabriele Tadini di Martinegro.

Tadini, one of the foremost fighting men in Europe and the greatest military engineer of the day, had been recruited by Fra. Philippe some months earlier. Once in Rhodes Tadini was so impressed by what he saw that he asked to be admitted into the Order. Philippe, himself impressed by the skill and piety of the unmarried but unprofessed Tadini, admitted him into the Langue of Italy as a Knight (of Magisterial Grace) Grand Cross, and this new Bailiff then threw himself with unrestrained gusto into strengthening the fortress. He had ravelins, inverted ‘W’ shaped trenches, dug in front of each bastion, re-sited batteries in order to provide optimum fields of fire, and near weaker parts of the walls and other possible points of attack he stationed piles of fascines (bundles of wood) and gabions (baskets of earth) with which to help plug any subsequent breaks and collapses. And, in due course, he became the Knights’ only effective line of defence against the thousands of Turkish miners and their warren of tunnels.

Until the siege of Rhodes, countermining had been a very haphazard business: defenders would simply lie with their ears to the ground desperately trying to hear the enemy sappers; when they located the general area of the underground incursion, shafts were sunk and countermines detonated in the hope of collapsing the enemy tunnels. It was a hit-and-miss affair, and generally there was a distinct advantage on the side of the attackers. Tadini reversed that advantage.

During the battle for Rhodes he created two entirely new, highly sophisticated mine warfare techniques. The first was to dig shafts terminating close to the area where the mines were thought to be about to be detonated and where time or the particular configuration of the defensive works precluded the use of countermines. These shafts provided escape routes for the blast, thus minimising the effect on the walls above. It was an extremely effective procedure, but in order that the location of these shafts, and indeed all of his countermining works, might be placed accurately enough to be effective, Tadini developed a device that is in worldwide use today — the geophone.

Tadini’s geophone was a sheet of fine parchment stretched tight over a frame to the resonant area of which were delicately attached several tiny bells. When this simple instrument was placed on the ground or upon the walls the bells responded to the blows of the picks and hammers beneath. By moving his geophones around and judging the intensity of their response Tadini was able to position his shafts and countermines with unprecedented precision. It was Tadini and his geophones which kept the enemy mine successes to a manageable level, and without doubt permitted the Knights to tenaciously hold onto their city in the face of constant assaults.

These assaults continued throughout August and September, culminating in the first mass attack of the 24th September, which fell on the southern ramparts, from the Post of Italy on the harbour, through those of Provence and England to that of Aragon on the western flank. Suleiman felt that the defences had been suitably weakened, and had by now learned that to attack a single Post at a time, no matter how well breached the walls, was to subject his troops to the withering enfilade fire of adjacent Posts.

That day he attacked along a whole front and opened hostilities with a dawn bombardment of unprecedented magnitude — it was said that the rumble of guns could be heard as far away as the Levant. When the guns ceased and the mines had been detonated, wave after wave of Turkish troops led by Heron-plumed Janissaries broke upon the shattered, smoking walls of the four southern bastions but, despite their legendary prowess, the Janissaries met their spiritual and physical match on the parapets and catwalks of Rhodes that morning. Raw courage was not enough. There, in the swirling smoke and dust, standing shoulder to shoulder in the confined spaces where the numerical superiority of the Turks was neutralised, blackened by fire and red with blood the steel-clad wall of Hospitallers stood fast behind a scything wall of broadswords.

The battle ebbed and flowed all of that day with the advantage first seeming to move in favour of one side, and then the other. At long last, after six hours of hand to hand combat, the Turks could do no more. It was finished. Neither threats nor inducements could any longer move the Turkish soldiery forward over smouldering rubble slick with the blood of their comrades and onto the blades and into the shot of the militant brethren.

Rhodes had held and Suleiman was forced to accept that the siege would not come to its end before the winter set in.

To be continued…

For links to previous essays by Seneca III, see the Seneca III Archives.

Excellent, Seneca III. I look forward to Part 3.

Yeah me too, it’s always nice to read about European history, it’s full of heroic deeds and people, honor, sacrifice, sense of duty, it’s just too amazing and worth to be remembered.

Ps: Gabriele Tadino was from a city called Martinengo not “Martinegro”.

I stand corrected, ‘italian guy’, and thank you. Rgds, S III.

They lose of course.

Then they win the sequel in Malta.

European solidarity at its best, wonder how the command and control interactions played out with the differing ethnolinguistic posts, the intergroup diplomatic skills must have been of the highest order.

It looks like the English were often stuck on the most likely wall the Turks would attack. The Theodosian Wall section that the Turks breached in the Siege of Constantinople was either Genoese or English.

Why did the English langue defend that section of wall? Why did the Turk attack it?

Was it the key section of wall?

For a great read on a similar siege event have a look at ‘The Great Siege: Malta 1565’ by Ernle Bradford. It covers the same order after they were forced to leave Rhodes and the subsequent attempt by the Ottomans to take Malta. Christian Europe at its best.

Ahem, Richard. Please see Part I, Note 7 and Caveat. 😉

Note to self – must remember to read end notes. Great piece by the way.