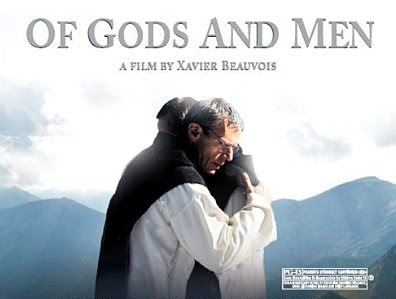

A French film entitled Of Gods and Men (Des hommes et des dieux), which won the Grand Prix at Cannes last year, has now been released with English subtitles. It is based on a true story of seven French monks kidnapped and massacred by Islamic bandits in Algiers in 1996.

Below is a review of the movie written for Gates of Vienna by the New York-based writer David Gurevich.

Of Gods and Men and Heroism of Faith

by David Gurevich

From pedophilia to corrupt Vatican banks, it has been a while since anyone in the media had a good word to say about the Catholic Church, one of biggest bêtes noirs of liberal media and artists. But in a new French movie by Xavier Beauvois called Of Gods and Men, such concerns are the last thing on the minds of eight monks quietly tilling their modest garden and treating villagers at the foot of Atlas Mountains in Algeria.

The monks are elderly and in poor health, but they happily persist in doing God’s work, and in between hoeing their garden and selling honey at the market and treating cases of eczema among local Arab children they never forget to praise the Lord. In fact, their choral singing, choreographed in a measured ascetic non-Hollywood way, makes for the most striking scenes. So how can such an unassuming group become a subject for such a richly dramatic and exceptionally timely film, based on the events that took place in Algeria in 1996?

Modernity invades abruptly. The anti-government Islamic Front issues an ultimatum: All foreigners must leave the country. At a nearby construction site, Croatian workers end up with their throats cut. The village elder’s granddaughter is stabbed for not wearing hijab. Finally, a local government official offers to post soldiers on the monastery territory (and is vehemently rejected) and then suggests that the monks should leave — “I can’t protect you.”

This is the real starting point when this deceptively simple routine of life of a religious community becomes a high drama of human heroism — and what inspires this heroism. Up until this scene, the Eight are rather nondescript old men in cassocks, save for their leader Christian (Lambert Wilson) and the elderly Dr. Luc (Michel Lonsdale).

As they debate whether they should leave or stay, they emerge as individuals, with their own human foibles and aspirations — one misses his family, his little grand-nephews and -nieces; yet he realizes that after so many years the monastery has become his real family, that serving God has glued them together as nothing else can, for it is the very meaning of the Faith and serving God that transcends human emotions. “I never meant to be a martyr,” says another. “But you already gave your life to God,” Christian argues.

And so they embark on this day-to-day struggle, trying to preserve faith in the face of everyday threats that come both from the Islamists who demand medical treatment and from the military who demand that the monks give up the rebels. And then there are the villagers who beg them to stay — “you are the branch, and we are the birds” — or, in other words, without you we’ll be done for. The monks cannot leave, and in a war like this the peaceful don’t survive.

Of course, there are political aspects of the movie to quibble with. The director plays down Islamic fanaticism and, following a liberal tradition, manages to make the rebels less repulsive than the government troops. Brother Christian’s last testament, portentously delivered off-screen, avoids any reference to Christianity and praises Islam. But perhaps this is what makes the film so timely — that this is where the beatific acceptance of a certain peace-loving religion takes you.

Artistically, too, Beauvois stumbles a bit — the real Trappist monks might well consider the choral scenes to be an expression of a sin of pride. But then he takes a lot of risks, and that deserves a hand. The most daring scene comes close to the end, when Brother Luc opens his last two bottles of wine and puts on a tape with — surprise! — the Swan Lake theme. The lush grandeur of Tchaikovsky’s music mingles with the flavor of wine you can almost taste, and it brings tears to the old men’s eyes.

Many will find this sequence over the top, with good reason; but to this viewer the scene was as much an expression of faith as Catholic chorales and a heartfelt celebration of some of our favorite things in the West — the music, the wine, and the ability of the most pious among us to enjoy them. (Surely some readers will note that none of these achievements can be claimed by “the religion of peace”).

Of Gods and Men won the Grand Prix at Cannes and is France’s official foreign-film submission for the Oscars. I suspect a surprise in the works.

For those wishing to read more on the subject, this is the Wiki article on the actual massacre.

Below is a video of the trailer for Of Gods and Men, including an additional clip from the movie. Many thanks to Vlad Tepes for YouTubing this video:

Looks like this one is on my list to pe-order on Amazon.

Having nothing to do with islam but everything to do with the grace and simplicity which can abound in christian faith is the documentary Into Great Silence (Die Grosse Stille) from a few years back.

It is long at just under 3 hours, and what dialogue there is, is minimal, but it is a beautifully moving glimpse into the lives of the carthusian monks in France.

I cried when I watched it, and for the beauty (there’s that word again) it shows in the love of the Lord.

Exactly what is “brave” about standing around passively while your life is about to be ended? I am sorry, but I just cannot respect anyone who will not defend themselves. I am an “eye for an eye” kind of person, and did military service. The way these monks think is simply ludicrous.

I had become independently interested in this incident a few weeks ago, and I’d never heard of this movie.

“It is based on a true story of seven French monks kidnapped and massacred by Islamic bandits in Algiers in 1996.”

I wouldn’t call them “bandits”. They were an Islamic commando unit sent (or volunteering as vigilantes) specifically to prosecute Islamic law. Also, this was no mere massacre: they beheaded them.

By chance, while researching the French sociologist and journalist Caroline Fourest and her exposé on Tariq Ramadan, I stumbled across her reference to a Belgian convert to Islam for whose book Ramadan wrote a glowing forward — one Yahya Michot.

Ms. Fourest wrote:

“In 1997, this Belgian convert to Islam was known to have revived a fatwa of Ibn Taymiyya supposedly demonstrating that the murder of monks at Tibehirine [sic] was justified from the religious point of view.”

A chilling postscript to my thread-following: In my years of researching various facets of Islam, I have experienced various roadblocks in that many of the top academic “Orientalist” journals of old are not only accessible only through having an academic password (as student or faculty) — which for a year I was able to borrow from a friend — but they are not even easily available through that avenue, since they have come under the wing of some academic organization called “Blackwell Synergy” (the particular university I had access to was not a member) whose subsidiary or partner, “Wiley Online Library” houses them online, most of them it seems available only through membership and purchase.

One particular academic journal, Muslim World, founded in 1911 at the Hartford Seminary in Connecticutt, is one of those journals exclusively available only through “Wiley On Line”. Time after time, I have found published articles whose titles and abstracts (sometimes available for free) seemed fascinatingly useful to piece together information about the history of Islamic doctrine and culture found nowhere else. Unfortunately, I am yet unable financially to afford paying for membership for these articles, and I no longer have academic access to even try to find a way.

Anyway, the punch line is this: This academic journal, Muslim World, used to be un-PCMC, in its early decades, but, as with virtually all Western institutions in the past 50-odd years (give or take), has become another unremarkable bastion for PC MC interpretations of Islam.

And guess who its senior editor is: none other than the Belgian convert to Islam who thinks the slaughter of these monks in Algeria was a legitimate fulfillment of Islamic law: Yahya Michot.

I walked out of the film.

It’s incredibly boring, devoid of any drama and invention, and desperately PC.

The monks are jolly good fellows, the Muslim population loves them, they outreach to Islam like hell, they fend off terrorists by quoting the Koran to them (only the good bits, of course), the bad guys who slash peoples’ throats look like Walt Disney villains with rolling eyes and beards dyed a deep black, and we’re exposed throughout the whole movie to a leftist world map on the wall with the word “solidarity” in big bold letters.

French catholic bloggers are in thrall because, for the first time, a local blockbuster is devoted to their religion without making fun of it or morphing it into some bizarre fantasy cult, but it was more than I could bear.

Robert Marchenoir:

sorry it didnt work out for you. i agree that monks are “jolly good fellows”, but I am curious about where you saw “outreach to Islam like hell”. Their leader does read and quote from Koran, but in my mind it hardly amounts to “outreach”. I am sure our community-organizer-in-chief would not call it that 🙂

David G (posing as lbertarian)

Libertarian : to me, that part when the abbot quoted the Koran to his local friendly visiting terrorists was pretty strong PC stuff…

Granted, in real life, it might have been a clever thing to do, maybe they actually did it, and maybe it saved their life once or twice.

The problem is, the whole movie is like that.

They never have a single problem with the local population. All their trouble comes from the terrorists (the tiny minority of misunderstanders of islam) and the authorities (although the authorities’ grudge against them is legitimate, because, you know, all of Algeria’s problems were caused by the evil French colonialists).

A local girl asks an old monk for advice about her love life. And he gives it to her. And he’s very wise and he treads very lightly but he still addresses the subject and the girl seems very happy with the answer and the old monk is the dream surrogate grandfather.

No problem about man-woman relationships, you see. The view on the subject is the same for muslims and christians. It’s only those rotten extremists from both sides who make life impossible. But actually everybody has the same God and blah blah blah.

At one point, the monks take part in a celebration in a little boy’s family (for his circumcision ?) ; they respectfully listen to the imam’s prayers, whose last words are something on the line of “Give us victory over the unbelievers” — meaning, them.

Now, that was an interesting note. That was something different from the nominal happy-clappy Kumbaya party line of “why can’t we get along all together”.

And what does the director make of it ? Nothing. Absolutely nothing. The monks stay put with their idiotic smile, as if the imam had said “Nice weather, isnt’it ?” or “Would you like your eggs fried or scrambled ?”.

It’s left entirely to the viewer to ponder the sinister implications of that phrase, and how it makes a potential mockery of all that “interfaith dialogue” atmosphere.

The imam’s phrase is not lost on counter-jihad types such as us, but chances are that the vast majority of viewers swallowed it without blinking.

I also found especially offensive the dialogue when the monks discuss tehir possible departure with a local family.

One of them says — and it’s a perfect phrase in the context : we’re like birds on a branch. Meaning : we might stay, but we also might be gone the next time you turn around, and God only knows.

That was very nice. But the next sentence ruins everything. A local woman replies with an ecstatic face : no, you are the branch, we are the birds.

Absolutely disgusting propaganda. Who can believe someone actually said such a thing ?

The film subject might have made for powerful drama. Instead, we are fed a documentary made by the Ministry of Information.

If only someone like Clint Eastwood had picked up the subject, that might have been a movie worth its salt.

Oh, and another one in retrospect.

Two monks are chugging along in their old clunker on a coutry road in the middle of nowhere. The engine stalls. They open the hood, but they don’t manage to make it start again.

A column of peasant women in traditional attire enter the screen from the left, walking along the road.

You see, although the monks are very poor and their car is on its last miles, the people of this country are even poorer, and they walk when you drive, you Western white bastard.

When the women arrive by the car, the conversation engages (those people are hospitable and friendly, you see, not like you selfish old geezers in Europe), and one of them offers to have a look under the hood.

The men oblige, and pronto, the Algerian woman in full traditional veil, from head to toe, has the car revving up again.

Lesson for you smelly islamophobes out there : all those stereotypes about Muslim wimin’ being inferior and subjugated by their men stem out of your racist worldview. Actually, deep under, unbeknown to you, it’s they who run things and repair old motors.

Oh, and also a message to you, male chauvinist pigs lurking in the dark : contrary to gender myths which are really social constructs imposed by the boot of patriarchal imperialism, men are not natural car mechanics ; illiterate wimin’ who don’t even drive are much, much better at it.

I found a book (Les veilleurs de l’Atlas) by a French compatriot to the monks — a fellow Catholic, he knew them personally and had visited their monastery frequently. His observations and assumptions about what went on, and about Muslims in general, reveal the disease of PC MC, even as it infects Catholics like himself.

And another book about the subject (The Monks of Tibhirine: Faith, Love and Terror) is just positively dripping in PC MC syrup, massaging into the the reader’s brain the TMOE (“Tiny Minority of Extremists”) dogma every which way but loose.

Which brings me to Clint Eastwood. A commenter above suggests that had Eastwood handled this material, it would have risen above the usual PC MC claptrap. Anyone who has seen Gran Torino (in which an old curmudgeonly white bigot in the span of a few months dissolves into a white liberal who loves Hmong immigrants so much he’s willing to martyr himself like Christ to protect them) and his Letters from Iwo Jima (which basically equates the fanatically mass-murderous Japanese of the 30s and 40s with the Americans — see this analysis) would realize Eastwood’s brain has been infected by PC MC as much as anyone else in, or out, of Hollywood.

Ha ! Thanks for ruining my illusions, Hesperado.

Actually, I saw Gran Torino, and it’s precisely that movie which made me yearn for a Clint Eastwood version of Gods and Men.

I can understand your point. I guess the glass looks half-full rather than half-empty from where I stand, given what French movies are nowadays.

A Clint Eastwood attitude would still be a huge improvement.

Robert Marchenoir:

For someone who was incredibly bored, you show an enviable memory of the movie play-by-play. At first I wanted to respond to you in a similar format; e.g., I thought the episode with a woman fixing a car was quite amusing because 1) I can easily see myself in this situation – in fact, have been, though not in Maghreb; 2) to me, it’s actually a sly dig at great macho Arab men, whose women somehow became forced to be car mechanics behind the scenes – not at a couple of elderly monks. Anyone who spent time in the 3rd world knows that macho men and skilled women are often the case.

Why is it an “outreach” for the abbot to quote Koran to bandits? It is painfully obvious from the scene that the bandit doesn’t know Koran at all, other than “kill the infidels”. To me, that was a great argument that we know their culture better than they know it themselves. I don’t need to tell you that for every study of the West by a Moslem there’s 10,000 studies of Islam by Westerners.

To me, when the villagers beg these seemingly powerless men to stay lest they are overrun by Islamic bandits (“bird-and-branch”), it makes for a far more powerful argument about relative strengths of religions than a Clint Eastwood with six-shooters would (actually, Magnificent Seven had a vaguely comparable situation). After all, what would Clint’s victory show? That we are better at war? but we already know that, don’t we? It’s the Islamists who live (whom we allow to live) under the illusion of their military prowess. But the film demonstrates the superior moral fiber of Christianity, and that’s more important.

And so on. Similar arguments can be made for each of your criticisms. Therefore I decided not to engage in a play-by-play debate. Our basic positions are too far apart. As I said in the review, the director is far from free from PC-BS; but in the world of the blind cineastes, this film definitely comes from a one-eyed king.

Why is it an “outreach” for the abbot to quote Koran to bandits? It is painfully obvious from the scene that the bandit doesn’t know Koran at all, other than “kill the infidels”.

That would be all well and good if we could prove that this Islamic commando unit was just a gang of Islam-illiterate “bandits”. Absent that proof, this sends a message that tends to reinforce probably the single most damaging and counter-productive meme operating today with regard to the problem of Islam: the TMOE (the “Tiny Minority of Extremists”). It’s all the more damaging when it’s in the vehicle of an acclaimed documentary.

After all, what would Clint’s victory show? That we are better at war? but we already know that, don’t we? It’s the Islamists who live (whom we allow to live) under the illusion of their military prowess.

Military superiority means little — indeed, can have disastrously counter-productive effects, if that superiority is hampered by inane Rules of Engagement such as we impose on ourselves now in Iraq and Afghanistan.

But the film demonstrates the superior moral fiber of Christianity, and that’s more important.

The better moral fiber of Christianity was demonstrated by the Templar Knights and other Christian military efforts of civilizational self-defense for the approximately thousand years during which nearly the entire West from the Levantine to England, from Rome to Spain, from from Greece to the Balkans, from Russia to American ships in the late 18th and early 19th centuries (not to mention the entire Middle East and North Africa which had become a part of Western civilization — for the half a millennium before the depraved monster Mohammed was born and his warmongering spawn unleashed) was in various ways and degrees assaulted, beleaguered, abused, attacked, enslaved, tortured and massacred by Muslims.

“…the director is far from free from PC-BS; but in the world of the blind cineastes, this film definitely comes from a one-eyed king.”

Logically, this would seem to make sense. But sometimes the “one-eyed” partial crumb we may grasp at in our hunger for the full meal actually perpetuates the overall situation of chronic starvation. In this case, all these partial memes — what I call the “asymptotic” vector — I think tend to reinforce precisely the very paradigm that is continuing to impede the West’s reawakening from its maddeningly irrational, and increasingly self-destructive, sleep with regard to the danger of Muslims.

We need to push the envelope, break the mold, tear apart the box aggressively, not politely chip away at the wall of the iceberg with icepicks only approved by the very same proponents of that iceberg on whose Titanic ship they hold us, as necessary fellow-travelers, hostage.