Thomas Bertonneau’s latest essay is a review of a recent book by the French political scientist Pierre Manent.

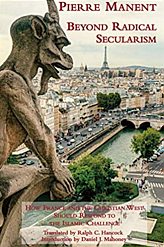

Pierre Manent: Beyond Radical Secularism — How France and the Christian West Should Respond to the Islamic Challenge

Reviewed by Thomas F. Bertonneau

Pierre Manent (born 1949), a former student of Raymond Aron’s who currently holds a professorship in political philosophy at the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales, Paris, has over the years written a dozen books devoted to the discussion of the liberal-modern dispensation — its origins, its basic assumptions, and its limitations. Unsurprising in a student of Aron’s, Manent is moderately right-leaning, at least in a contemporary French context, in that he defends classical liberalism, disparages the authoritarian liberalism that has replaced it, advocates for the legitimacy of the nation-state, and turns his considerable skepticism on the European Union. Like a number of his contemporaries on the French Nouveau Droit, Manent insists that by the compelling force of their history and culture, France and its European sister nations are Christian nations and that they derive the fundamental decency of their political arrangements at least in part from a specifically Christian view of man and the world. In his expository style, Manent qualifies as quintessentially French: He argues his theses with thoroughness and subtlety and eschews any rhetoric of provocation. His prose gives an impression of coolness, calmness, and steadiness, qualities that incline a reader to concede the argument, if only while he is reading it.

Pierre Manent (born 1949), a former student of Raymond Aron’s who currently holds a professorship in political philosophy at the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales, Paris, has over the years written a dozen books devoted to the discussion of the liberal-modern dispensation — its origins, its basic assumptions, and its limitations. Unsurprising in a student of Aron’s, Manent is moderately right-leaning, at least in a contemporary French context, in that he defends classical liberalism, disparages the authoritarian liberalism that has replaced it, advocates for the legitimacy of the nation-state, and turns his considerable skepticism on the European Union. Like a number of his contemporaries on the French Nouveau Droit, Manent insists that by the compelling force of their history and culture, France and its European sister nations are Christian nations and that they derive the fundamental decency of their political arrangements at least in part from a specifically Christian view of man and the world. In his expository style, Manent qualifies as quintessentially French: He argues his theses with thoroughness and subtlety and eschews any rhetoric of provocation. His prose gives an impression of coolness, calmness, and steadiness, qualities that incline a reader to concede the argument, if only while he is reading it.

In Beyond Radical Secularism — How France and the Christian West Should Respond to the Islamic Challenge (2016), Manent, compelled by the outbursts of Muslim violence in his country, turns his attention to the question of Islam and France. Not only in style, but in his approach to the Muslim question, Manent differs from others such as Guillaume Le Faye, Eric Zemmour, or Alain de Benoist. To their intransigency — which only responds to Muslim intransigency, after all — he proposes a type of meliorism. He is a measured optimist. His book, divided into twenty numbered chapters, none exceeding five or six pages, bears close inspection.

Even Manent’s title has a function in his argument. The first of its elements suggests a need to transcend radical secularism, the existence of such a necessity implying the inadequacy of radical secularism, whatever that might prove to be. Manent soon enough explains what it is, of course. In its second element, Manent’s title makes a reference to France and the Christian West, once again with an important implication — namely that France and the Christian West differ in their nature from radical secularism and should perhaps not be identified with it. Contemporary Euro-skeptical discussion, furthermore, generally associates radicalism with Islam, but Manent’s title indirectly raises the question whether the Muslim problem might stem from a collision of two stubborn radicalisms — Islam itself and the postmodern, radically secular anti-nation. An important preliminary gesture of Manent’s argument entails his critique of the postmodern anti-nation, into which the France of Tradition has morphed. Despite Manent’s cool, calm, and collected manner, the reader will not miss the urgency and the frequent rapier-like penetration of that critique.

Even Manent’s title has a function in his argument. The first of its elements suggests a need to transcend radical secularism, the existence of such a necessity implying the inadequacy of radical secularism, whatever that might prove to be. Manent soon enough explains what it is, of course. In its second element, Manent’s title makes a reference to France and the Christian West, once again with an important implication — namely that France and the Christian West differ in their nature from radical secularism and should perhaps not be identified with it. Contemporary Euro-skeptical discussion, furthermore, generally associates radicalism with Islam, but Manent’s title indirectly raises the question whether the Muslim problem might stem from a collision of two stubborn radicalisms — Islam itself and the postmodern, radically secular anti-nation. An important preliminary gesture of Manent’s argument entails his critique of the postmodern anti-nation, into which the France of Tradition has morphed. Despite Manent’s cool, calm, and collected manner, the reader will not miss the urgency and the frequent rapier-like penetration of that critique.

What is radical secularism? Manent defines radical secularism as the opinion, pervasive in modern Europe since the end of World War Two, that views religion merely and strictly “as an individual option, something private, a feeling that is finally incommunicable.” Manent argues, however, that this opinion is not native to those who hold it, but rather is the result of a propaganda regime in place for many decades. “The power of this perspective over us,” Manent writes, “is all the greater because it is essentially dictated by our political regime, and because we are good citizens.” It belongs to the bland conformism of the modern — or postmodern — person that he wishes to participate in such self-lauding phenomena as “enlightenment” and “progress.” Not even “the acts of war committed in early 2015 in Paris” seem to have shaken that conformism, which confirmed its blandness with a brief rush of emotion followed by a return of the characterless routine. France finds itself in a state of “paralysis,” Manent concludes. Its program, from the presidency down through the institutions right to the conformist mass of citizen-individuals, appears to be to see nothing and to do nothing. The Muslim problem exists, according to Manent, because the French state is weak and cannot produce the secularity, which would integrate Muslims, and which it declares as its program. Whereas “the State of the Third Republic had authority” and “represented that all held sacred,” as Manent argues; “our state [the Fifth Republic] has abandoned its representative ambition and pride, thus losing a good part of its legitimacy in the eyes of citizens.”

Manent continues: “Our state now obeys a principle of indeterminacy and dissipation.” Indeed, the French state, committed to the European Union, is programmatically self-minimizing. This trend attaches to another: The rising hostility to and elision of national culture and national identity. Manent points out that “the work of the state… has tended to deprive education of its content, or empty these contents of what I dare call their imperatively desirable character.” Under the Third Republic, pride in the achievement of one’s nation — or at the very least, the explicit acknowledgment of those achievements — expressed itself robustly and informed the national curriculum. The existing curriculum, in the name of multiculturalism, has elbowed the lesson in what it means to inherit the French nation out to the margin of the page or out of the textbook altogether. “How can we begin from the beginning,” Manent asks, “and gather children together in the competent practice of the French language, when we have done so much to strip this language of its ‘privilege?’” Given that secularity itself is such an empty concept, how might teachers teach secularism, the primary principle supposedly of the state — say, to Muslim students who crowd France’s urban schools? One can teach the heritage of a nation, but one finds himself hard-pressed to teach a self-evacuating notion. “Under the name of secularism we dream of a teaching without content that would effectively prepare children to be members of a formless society in which religions would be dissolved along with everything else.”

Manent returns repeatedly to the place of religion in the state. When the state replaces religion as the central institution of the society — something which has never happened in Islam, but which forms the pattern in the West, with France more or less leading the way since 1789 — and when the state constitutes itself on vacuous non-principles and a general hostility to tradition — it should come as no surprise that “paralysis” results. The state claims to be “neutral among the religions.” In reality, Manent writes, the state seeks to neutralize religion, but of the religions currently practiced in France, one in particular has shown itself unwilling to be neutralized. Manent pronounces: “This idea of neutralization, which amounts to making religion disappear as something social and spiritual by transforming the objectivity of the moral rule into the subjective rights of the individual, is the imaginary transposition of a misinterpreted historical experience to a misunderstood new situation.” The “misinterpretation of experience” concerns the view that Christianity, and particularly Catholic Christianity, is divisive, bigoted, and weakening. The “misunderstood new situation” is the presence suddenly of millions of religious believers in the nation of Jeanne-d’Arc and the silly expectation that sooner or later, they will be eating brie, drinking cabernet, and listening to Maurice Chevalier, without anyone having to do anything to bring about the metamorphosis. Were France still a Catholic nation, were it merely still the Third Republic, it might have the fortitude to assert its sovereignty. It would not tolerate the desecration of religious monuments or the slaughter of its citizens.

The presence of Islam in France naughtily contradicts a shibboleth of the supposedly neutral multicultural agenda, which is, in effect, an anti-Western, anti-Christian campaign. The spokesmen of that campaign never cease to accuse Europeans and Christians of violence, but violent Muslims shoot and stab concertgoers in a rock-and-roll nightclub, slit the throat of an aged priest serving mass, and commit rape and assault. In this way Islam becomes an embarrassment to its defenders. The institutions, dominated by self-lacerating doctrines, prefer then not to see Muslim violence — hence Manent’s comments on the short-lived outrage in response to the Bataclan incident. The state, which endorses the self-lacerating doctrines and more than that incorporates and subsidizes them, has made of itself an anti-state or rather an anti-nation. The state needs to become a nation again. Take the issue of borders — not only of national political borders. The anti-nation effaces borders. Within Europe and among Europeans the effacement of political borders probably qualifies as a viable or at least a non-harmful program. Despite their de-Christianization, Europeans remain a well-behaved, rule-following people. That is to say, the Europeans possess internalized moral borders. One demonstration of the existence of those internalized moral borders is the fact that Europeans do not extract revenge on Muslims for what Muslims do to them. The French state, Manent points out, has not been able, and seems not even to care, to inculcate among Muslims those same internal moral borders. It is a failure that costs lives every week.

Multiculturalism, the most prominent of the self-lacerating doctrines, mucks things up in another way. Manent compares the multicultural regime with the socialist regimes of the middle of the last century. Noting that “the social movements summed up in the word ‘socialism’ were driven by an affirmation concerning the social truth” and that they “affirmed that common life had to be remade on the basis of class condition,” the advocates of those movements raised two questions. What part would the proletarians to play in “the common life”; and to what degree would “the common life” become proletarian? Under the multicultural regime, complaints about the social condition have ceased to refer to truth or to “the common life.” Manent writes how “today’s claims aim directly at no transformation of the social whole, which they do not at all have in view or take into consideration,” but they correspond to something “circular or self-referential.” While “there is still a demand that an injustice be rectified,” there is no explanation “in view of what” it should be rectified, or of how the rectification will affect “the common life” positively. Multiculturalism, Manent argues, by endowing on Muslims the protected status of perpetual victimhood, immunizes them from the necessity of explaining themselves; it excuses them from responsibility, along with other so-called minorities, thereby rendering them non-agents, lacking in moral capacity, as though they were a force of nature.

Manent’s analysis wears the garment of plausibility as far as it goes. When he broaches his program, however, the garment can begin to look a bit tattered.

“Just as socialism asked itself what part proletarians should play in the common life,” Manent writes, “and what proletarian character this common life should take on, we would all benefit if our Muslim fellow citizens asked themselves what part they wished to take in the common life of our country, and inseparably — but this question is for all citizens — what transformation of the common life we should expect, hope for or fear, from this participation.” Of course, Muslims are not going to ask themselves these questions spontaneously. Islam dislikes questions. Manent acknowledges that Muslims would need to be asked, forcefully, to ask themselves those questions and to report their answers in a public way. It is true that, in its weakness, the French state has never done this and never will do it. Manent believes that a revived French nation might do it and that doing it might establish a productive dialogue between France and its Muslims. In a nation as opposed to a state, citizenship has a value. Citizenship, the freedom to participate fully in public life, can be traded for concessions. A revived French nation, replacing the lost value of citizenship, would be able to offer Muslims, Manent argues, something of value in exchange for concessions. Manent hopes to lure Muslims out of their high-walled self-ghettoization. He places his hope partly on the precedent of the European Jews, who, released from their ghettoes, rapidly integrated themselves in their respective European societies.

Manent’s multi-part thesis, which also constitutes the outline of a program, might be summed up as follows:

| (1) | that the Muslims of France are there to stay; | |

| (2) | that their sodality poses a problem, characterized as it currently is by hostility to the host-country; | |

| (3) | that, however, the nation of France also has a problem — namely that it is no longer a nation whose people acknowledge a common cultural content and pursue common concerns, but that it has become a socially atomistic rights-based polity that pits itself, in effect, against the idea of nationhood; | |

| (4) | that the solution to the Muslim problem requires first the restoration of French nationhood and the revival of citizenship; | |

| (5) | that if the restoration of nationhood were to happen, the revived nation and its citizens would be justified in asking French Muslims what they see as their citizen-role in the nation and what they want from the nation, which, Manent argues, is currently not the case; and | |

| (6) | that Muslims, as the condition of the extension to them of a revived citizenship, must accede to the demand to be loyal to the nation first and to limit what they want on the basis of that loyalty. |

Both the argument and the implied program contain a good many ifs. Manent also appears to assume that nothing will stop Muslim immigration and that Muslims are in Europe, and in France, to stay. Maybe that is so. Those many ifs might nevertheless constitute a noticeable glitch in Manent’s persuasiveness.

Another possible glitch in Manent’s persuasiveness is that he argues too much in the mode of ought and too much confuses it with the mode of will be. For example, supposing that the French state could find its way once more to being the French nation, even to the extent of recognizing itself as historically a Catholic nation, and supposing that it implemented a vigorous program to acculturate Muslims, would Muslims get with the program? The most likely answer comes in the negative, citing the history of Islam and Muslim parochialism as its evidence. Rational appeals work effectively when the appealing party makes them to other rational people. When the party receiving the appeal is not rational, rationality will prove itself ineffective. In any case, Muslims have in effect already answered the questions that Manent would like to put to them. They want a global caliphate governed by sharia. They see themselves as exclusively entitled to the whole of everyone’s common life. Manent concedes that “the common life” hardly exists anymore in France, which like the other European countries has atomized itself into a mass of rights-endowed individuals who see overwhelmingly to their personal needs and rarely think of themselves as citizens of a polity. Nor do they think of the people who surround them in the public square as fellow citizens, but only as anonymous others. Every moral person will agree that such a situation ought to be altered, but as to how it might be altered — who knows the procedure?

At moments in Beyond Secularism yet another potential glitch irritates the reader. It is the flaw of inconsistency. Manent very succinctly describes the European emergency and one wants to respond to his clarity of vision with a hearty bravo! “Islam is putting pressure on Europe and advancing into Europe,” Manent writes; he points out that the Muslim colonization in Europe finds financial backing in the “unlimited capital” of the Gulf countries and that Islam encourages Muslims to use violence against non-Muslims. “We interpreted the massacre of the Charlie Hebdo journalists as an attack on freedom or on our ‘values,’” but the murderers of those victims saw what they perpetrated “as punishment for blasphemy.” That is a yawning gap of perspectives. Manent acknowledges that mass-murders of Europeans by Muslims are acts of “war.” It entails a difficulty then to understand what Manent means when he asserts that Muslim colonization and the financial backing of it by the Emirates and homicidal jihad “are entirely distinct phenomena.” Neither is it clear that “the immense majority of our Muslim fellow-citizens have nothing to do with terrorism, but terrorism would not be what it is, it would not have the same reach or the same significance, if the terrorists did not belong to this population and were not our fellow citizens.” The exasperated question poses itself: In what meaningful way were the Charlie Hebdo murderers “fellow citizens” of those whom they murdered? And when a closed sector of society fails to police itself, or to rebuke publicly its miscreants when they perpetrate enormities, what assurance does that provide that a majority of it has “nothing to do” with outrages perpetrated by its members?

Manent closes once more with reality and regains his consistency somewhat in his later chapters when he returns to the critique of the postmodern state. “Islam has sprung up in a Europe that has dismantled its ancient parapets, or has let them crumble.” Parapets are walls and walls are borders. “No border must be allowed to obstruct the free movement of capital, of goods, of services, of people, just as no law must circumscribe the unlimited right of individual particularity.” Europeans live, Manent asserts, a “life without law in a world without borders,” and “this has been the horizon of Europeans for at least a generation. At the very moment when “Europe intends to abandon the political form that is proper to it,” Manent writes, Islam, “which has never found its own political form,” appears in its midst. To abandon the native political form amounts to a campaign against history, a denial of identity, a self-uprooting. The post in the postmodern condition becomes a sign of cultural nihilism. “The history of Europe,” Manent writes, “is unintelligible if one does not take into account… a notion elaborated by ancient Israel, reconfigured by Christianity and lost when the European arc was broken.” Manent refers to the notion of the Covenant. A revived French-Catholic nation might offer Muslims a Covenant.

Is Manent proposing that the real way to address Islam in Europe is to undertake the conversion of Muslims by inviting them into the Judeo-Christian Covenant perhaps one by one? It seems that the answer is yes, but there is a companion question. Is Manent proposing that the French must first re-convert themselves? Here too, it seems that the answer is yes. This interpretation has in its favor Manent’s usage of the term border, which means in one context a national frontier guarded by the customs and immigration police, but which means in another context an internalized moral limit beyond the sanction of which one will refrain from acting. The careful reader of Beyond Radical Secularism will perhaps characterize the book on closing it by its hesitancy. Manent hesitates to say outright what he so subtly implies. He understands that to engage in immediate candor would be counterproductive. It might be that just this hesitancy, or just this indirection, redeems the book, whose occasional inconsistencies might be interpreted as one expression of it. I come back to my earlier description of Manent as a “measured optimist.” And what is a “measured optimist” but a Christian?

Thomas F. Bertonneau has been a college English professor since the late 1980s, with some side-bars as a Scholar in residence at the Russell Kirk Center for Cultural Renewal, as a Henri Salvatori Fellow at the Heritage Foundation, and as the first Executive Director of the Association of Literary Scholars and Critics. He has been a visiting assistant professor at SUNY Oswego since the fall of 2001. He is the author of over a hundred scholarly articles and two books,Declining Standards at Michigan Public Universities (1996) and The Truth Is Out There: Christian Faith and the Classics of TV Science Fiction (2006). He is a contributor to The Orthosphere and the People of Shambhala website, and a regular commentator at Laura Wood’s Thinking Housewife Website. For his previous essays, see the Thomas Bertonneau Archives.

Manent deludes himself thinking that Islam will assimilate if France would get its act together. The point that all the socialists, Marxist and others of their ilk miss is that Islam is in Europe to conquer and thus will never assimilate.

If Europe and France want to survive as a part of Western Civilization, they must deal with their paralysis of the ‘elite leadership’, come to their senses, realize that they are now engaged in a real war with Islam, gear up the Armed Forces and expel them from the continent. Short of this action, Western Civilization dies a slow death on the continent.

That is why I wrote that Manent seems to confuse the mode of “ought” with the mode of “will be.” That is also why I refer to the many “ifs” in Manent’s argument. Nevertheless, in his characterization of the existing French state (which is, in effect, an anti-nation), Manent has gotten it right. Therefore his thesis retains validity: Before anything can happen in respect of France’s Muslims, something must happen to France.

THANK YOU, Gates of Vienna, for posting this. Excellent! It may be a case of the book review being as good or better than the book being reviewed. I hope not, because I just ordered a copy from Amazon, based on this review. Amazon(Canada) said “Hurry. Just 5 copies left!” They might be telling the truth.

Necessarily a review leaves out a good deal that is in the book. I have certainly not spoiled anything for anyone who wants to acquire Beyond Radical Secularism and read it. I repeat that, when he is focused, Manent is a very subtle expositor of ideas.

Manent acknowledges that mass-murders of Europeans by Muslims are acts of “war.” It entails a difficulty then to understand what Manent means when he asserts that Muslim colonization and the financial backing of it by the Emirates and homicidal jihad “are entirely distinct phenomena.”

This is something I’ve often considered, wondering how differently things might have gone without all the petrodollars flooding Europe and the U.S. There still would be mass immigration into former colonial states like the UK and France – the UN pushing European guilt. But with the petroleum money missing, many of the mosques wouldn’t exist. In turn, Islam would be less militant or radicalized.

Militant atheism makes monads of its adherents. Gabriel Marcel described this life sans transcendence well, though he couldn’t have guessed its eventual anti-state, anti-borders splintering of a people and its culture. Fortunately, we have the examples of the Visegrad Four, of Italy and Argentian and Brazil, to see what an alternate future could be.

Populism is on the rise. In France, Marine Le Pen continues to fight for the regeneration of France. I hope she succeeds eventually.

One who did foresee such things was the Russian philosopher Nicolas Berdyaev, who lived most of his life in France after being exiled by Lenin. I recommend Berdyaev’s Fate of Man in the Modern World (1935). It is relatively brief, in four entirely tractable chapters, and compelling throughout. There aren’t many references to Berdyaev anymore although I just ran across one in Remi Brague’s recent book, The Legitimacy of the Human. Brague quotes Berdyaev with approval. If any were interested, I have put up an essay at The Orthosphere on Berdyaev under the title “Nicolas Berdyaev on Culture and Christianity.”

https://orthosphere.wordpress.com/2018/07/09/berdyaev-on-culture-and-christianity/

Marin Le Pen is why I am not blankly pessimistic about France.

Could Islam be regarded as the religion of the Socialist?

Rhetorical question seeking an answer.

Socialism is a form of collectivism and Islam is a form of collectivism.

Copied and pasted on my Fb page. Merci beaucoup.

So many interesting points, from Manent and his reviewer Bertonneau. I’ll add my ten cents’ worth to one:

Manent says that once freed from their ghettos, European Jews “rapidly integrated themselves…” Well, some did; like Christians, they were influenced by the Enlightenment. A leading figure in this movement was the autodidact Moses Mendelssohn (grandfather of the composer). Others- broadly those dubbed “ultra-orthodox”- became more obscurantist. Islam has not had even this window of opportunity.

At only a slight tangent (?), here’s something I saved a few days ago; the wording of the link is self-explanatory: https://theconversation.com/religious-decline-was-the-key-to-economic-development-in-the-20th-century-100279

The Ultra-Orthodox opted out of the general life, Manent’s “common life.” They continue to exist, but they have no influence. They are like the Mennonites or the Amish. You might say that Judaism bifurcated with its liberation after the Napoleonic wars. There is a tiny bifurcation in Islam, but generally your description of Islam is valid.

Religious decline might be the key to increased wealth because peoplekind become ruthless, unscrupulous, unconscionable, immoral, . . . Get money through any means no inhibitors even through pornography.

Religious decline on the part of the West has helped islam to conquer and colonize the West in a strange unprecedented way and method: i.e. we invite them to colonize and subjugate us. We have no religion to defend and by extension we believe in nothing to defend. But the whole onus of all troubles that befall us lies with the Traitors, who are sheer abject cowards who help islam to destroy us for votes, and have no will to stop this invasion until “something” horrible happens and then it will be too late for islam will be so strong that it will overrun our cities and overwhelm the hedonist population and we will be worse than King Lear.

Western Human Rights is a joke: Just see what’s happening to Hindus in Bangladesh, Christians in Sceh, Egypt and Pakistan. But the west does not know because mulims cannot be blamed.

Western govs. have been paralyzed by slam. Have given up any resistance to the oppression and subjugation inflicted on us. The low and base process of elections have destroyed our nations: Winning and becoming PM is the ultimate goal at the expense of destroying the nation.

The West has been in a decline since the mid-19th century. It is a slow-motion decline, thus difficult for any one generation to see the full scope.

However, I don’t agree with your dystopian view. There is a movement turning away from this course, and we’re seeing it in the news about the VIsegrad Four, Italy, Argentina, and Brazil. Plus a bit of Austria, the break-away parties in Sweden, Denmark’s pushback against Islam, etc.

People are giving up on the administrative bureaucracy in small but telling ways. In the U.S., it took electing a man whose moral life is questionable but whose ability to turn the country around is far superior to the moral midget he ran against.

Even in the UK, universities are saying “enough with the safe spaces”, plus seeing a marked uptick in attendance at worship services in its cathedrals. And in the U.S., Christian colleges teaching the old classical courses are sprouting up everywhere, not to mention what is available online. State colleges like Evergreen may well go under while the small, classical colleges continue to gain students.

The ruthless internet with all its downsides will revolutionize education, medicine, etc.

“There is a movement turning away from this course, and we’re seeing it in the news about the VIsegrad Four, Italy, Argentina, and Brazil.”

Amen. I hope and pray the Lord’s Prayer that your optimistic sentiments will turn out to be fulfilled.

I want to remember in these horrific times that :

And I tell you, you are Peter, and on this rock [a] I will

build my church, and the gates of hell [b] shall not prevail

against it.

That’s some consolation for my realistic worries.

Why would Moslems want to assimiliate into a culture that hates itself and has become fundamentally weak?

The fact this is an issue is because Moslems are becoming a significant part of the population precisely because French society is weak.

It also is a prime example of how assimilationist policies by the French state have been total failures as the only real reason for immigrant children to assimilate is if they’re a small minority within a French milieu.

Given the penchant to load France with people from its former colonies, none of which were colonies by choice, it’s a little far-fetched to expect the descendants of the people you conquered to be great supporters of French culture once they gain the numerical superiority. This is especially true when the leftwing has promoted the evils of colonialism and therefore the native French people.

DanielK, Exactly

First we must know ourselves. Know our culture.

It is “us” who must strengthen our culture, knowledge, reasoning, in many things, and also to be able to appreciate what we have got.

We in ourselves must become the “strong horse”.

Some will feel a frustration so seek alternatives and find islam.

Others will take the opportunity to profit and jump ship and seek the “refuge” that islam offers.

It is one of the reasons I enjoy and keep coming back to GOV.

Thanks Baron & Dymphna.

Yes, and yes for all that you stated. Jane Austen says man is servile. One reason islam is accepted in the west is that islam arrived in the west in the form of a rough diamond on a strong horse, when the west is declining in every aspect: religiously, politically and socially.

How did Osama bin Laden know that the real love and fascination of islam and muslims would start after shedding the infidels’ blood. $2 billion were spent by Americans on Sept. 12, 2001 buying books on islam to “learn” about the new wonderful “religion” that they had remotely heard about and now it is knocking at their doors.

Immigration gates were opened wide after the corpses and blood of nine eleven. Bush declared islam a religion of peace while standing on the smoking ruins of Twin Towers . . . what an irony and courage and cleverness.

In the UK, many afro-caribbeans, and Hindus and Sikhs originating from the sub-continent, have integrated well, notwithstanding our colonial history.

It’s hard to imagine that a society that is free and secular in every way (say we are free, creative, loving, altruistic but otherwise atomized) could survive a determined attack by an adversary who has a strong central idea, a common belief that is threaded throughout its people, and is using every tool of war, demographics, politics, terrorism and ideology as the means to advance its cause. Think: A scattered group of agnostic surfers, academics, artists and entreprenuers attacked by a disciplined company of Nazi special forces military.

The singular strength of mankind is through its brain and penchant for social cooperation. That is why a common idea is needed…to attach our social urges together in a common effort.

Somehow we are going to need a unifying idea. Maybe simply the love of freedom is enough, but probably not. Maybe reformed resurgent Christianity?… Doesn’t sound likely. What else? We could get lucky and all be threatened by some orthogonal catastrophe, like a Long Valley volcanic caldera blowing or an asteroid. Maybe the Islamic idea could be deconstructed in some way?

But we do have what is called a hard problem.

HARD TRUTHS are “out there” and will persist and rule over the world whether or not we close our eyes to them as a society. (Or bury them under sophisticated layers of esoteric verbiage.) Something like “western culture” exists–from the Urals to Tierra del Fuego–you can call it “Christian” if you like.

Like it or not, we live IN it, not WITH it.

This mental, moral and philosophical excrement we know as ‘islam’ is, was, and will ALWAYS be diametrically opposed to ‘US’ and this way of like that we hold dear.

The term “HATE” doesn’t even come close…………..Their goal of ‘submission’ or genocide is essentially the same thing.

Their mere existence is due to their state of WAR with the world –one that only has existed for 1400 years now. (Too bad it is now so well funded by (our) petrodollars.)

Howasbout we start WITH THIS ‘TRUTH’–for a change?

Fundamentally incompatible.