The essay below by Seneca III is the latest in the “End Times of Albion” series. Previously: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, and Part 5.

Lessons From History and Organising for the Present

The End Times of Albion, Part 6A

by Seneca III

The England of 1819 was in many ways similar to the England we find today. The Napoleonic wars which began in 1803 had ended at Waterloo some three years previously on 18th June 1815, and a war-weary people began to look inward at the state of political affairs at home after dealing with the dictator Bonaparte.

What soon became apparent to them was that all was not well. By the beginning of 1819, the pressure generated by poor economic conditions, coupled with the relative lack of suffrage in Northern England, had enhanced the appeal of political radicalism. In response, the Manchester Patriotic Union, a group agitating for parliamentary reform, organised a demonstration to be addressed by the well-known radical orator Henry Hunt.

Shortly after the meeting began, local magistrates called on the military authorities to arrest Hunt and several others on the hustings with him, and to disperse the crowd. Cavalry charged into the crowd with sabres drawn, and in the ensuing mayhem 15 people were killed and 600-700 were injured. The massacre was given the name Peterloo in an ironic comparison to the Battle of Waterloo, which had taken place four years earlier.

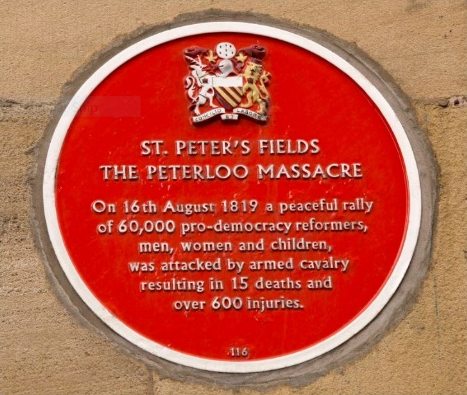

Peterloo’s immediate effect was to cause the government to crack down on reform, with the passing of what became known as the Six Acts. It also led directly to the foundation of The Manchester Guardian (now The Guardian), but had little other effect on the pace of reform. Peterloo is commemorated by a plaque close to the site, a replacement for an earlier one that was criticised as being inadequate, as it did not reflect the scale of the massacre.

Background

In 1819 Lancashire was represented by two members of parliament (MPs). Voting was restricted to the adult male owners of freehold land with an annual rental value of 40 shillings or more, and votes could only be cast at the county town of Lancaster by a publicly spoken declaration at the hustings. Constituency boundaries were out of date, and the so-called Rotten Boroughs had a hugely disproportionate influence on the membership of Parliament compared to the size of their populations: Old Sarum in Wiltshire, with one voter, elected two MPs, as did Dunwich in Suffolk, which by the early 19th century had almost completely disappeared into the sea.

The major urban centres of Lancashire, with a combined population of almost one million, were represented by either the two county MPs for Lancashire, or the two for Cheshire in the case of Stockport. By comparison, more than half of all MPs were returned by a total of just 154 owners of rotten or closed boroughs. Of the 515 MPs for England and Wales 351 were returned by the patronage of 177 individuals and a further 16 by the direct patronage of the government: all 45 Scottish MPs owed their seats to patronage. These inequalities in political representation led to calls for reform.

Exacerbating matters were the Corn Laws, the first of which was passed in 1815, imposing a tariff on foreign grain in an effort to protect English grain producers. The cost of food rose as people were forced to buy the more expensive and lower quality British grain, and periods of famine and chronic unemployment ensued, increasing the desire for political reform both in Lancashire and in the country at large.

Against this background, a “great assembly” was organised by the Manchester Patriotic Union, formed by radicals from The Manchester Observer. The newspaper’s founder Joseph Johnson was the union’s secretary. He wrote to Henry Hunt asking him to chair a meeting in Manchester in August 1819. Johnson wrote:

“Nothing but ruin and starvation stare one in the face; the state of this district is truly dreadful, and I believe nothing but the greatest exertions can prevent an insurrection. Oh, that you in London were prepared for it.”

Unknown to Johnson and Hunt, the letter was intercepted by government spies and copied before being sent to its destination. The contents were interpreted to mean that an insurrection was being planned, and the government responded by ordering the 15th Hussars to Manchester.

The mass public meeting planned for 2 August was delayed. The Manchester Observer reported it was called “to take into consideration the most speedy and effectual mode of obtaining Radical reform in the Common House of Parliament” and “to consider the propriety of the ‘Unrepresented Inhabitants of Manchester’ electing a person to represent them in Parliament”. The magistrates, led by William Hulton, had been advised by the acting Home Secretary, Henry Hobhous, that the election of a member of parliament without the King’s writ was a serious misdemeanour, encouraging them to declare the assembly illegal as soon as it was announced on 31 July. The radicals sought a second opinion on the meeting’s legality, which was that “The intention of choosing Representatives, contrary to the existing law, tends greatly to render the proposed Meeting seditious; under those circumstances it would be deemed justifiable in the Magistrates to prevent such Meeting.”

The meeting on 9 August was postponed after magistrates banned it to discourage the radicals, but Hunt and his followers were determined to assemble and a meeting was organised for 16 August, with its declared aim solely “to consider the propriety of adopting the most LEGAL and EFFECTUAL means of obtaining a reform in the Common House of Parliament”. The press had mocked earlier meetings of working men because of their ragged, dirty appearance and disorganised conduct, but the organisers were determined that those attending the St Peter’s Field meeting would be neatly turned out and march to the event in good order. Samuel Bamford, a local radical who led the Middleton contingent, wrote that “It was deemed expedient that this meeting should be as morally effective as possible, and, that it should exhibit a spectacle such as had never before been witnessed in England.” Instructions were given to the various committees forming the contingents that “Cleanliness, Sobriety, Order and Peace” and a “prohibition of all weapons of offence or defence” were to be observed throughout the demonstration. Each contingent was drilled and rehearsed in the fields of the townships around Manchester adding to the concerns of the authorities. A royal proclamation forbidding the practice of drilling had been posted in Manchester on 3 August, but on 9 August an informant reported to Rochdale magistrates that at Tandle Hill the previous day, 700 men were “drilling in companies” and “going through the usual evolutions of a regiment” and an onlooker had said the men “were fit to contend with any regular troops, only they wanted arms.”

Consequently, the magistrates were concerned that it would end in a riot, or even a rebellion, and had arranged for a substantial number of regular troops and militia yeomanry to be deployed. The military presence comprised 600 men of the 15th Hussars; several hundred infantrymen; a Royal Horse Artillery unit with two six-pounder (2.7 kg) guns; 400 men of the Cheshire Yeomanry; 400 special constables; and 120 cavalry of the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry who were relatively inexperienced militia recruited from among local shopkeepers and tradesmen, the most numerous of which were publicans. Recently mocked by The Manchester Observer as “generally speaking, the fawning dependents of the great, with a few fools and a greater proportion of coxcombs, who imagine they acquire considerable importance by wearing regimentals, they were subsequently variously described as ‘younger members of the Tory party in arms’, and as ‘hot-headed young men, who had volunteered into that service from their intense hatred of Radicalism’. The socialist writer Mark Krantz has described them as “the local business mafia on horseback”.

The British Army in the North was under the overall command of General Sir John Byng. When he had initially learned that the meeting was scheduled for 2 August, he wrote to the Home Office stating that he hoped the Manchester magistrates would show firmness on the day:

I will be prepared to go there, and will have in that neighbourhood, that is within an easy day’s march, 8 squadron of cavalry, 18 companies of infantry and the guns. I am sure I can add to the Yeomanry if requisite. I hope therefore the civil authorities will not be deterred from doing their duty.

The revised meeting date of 16 August, however, coincided with his visit to the horse races at York, a fashionable event at which Byng had entries in two races. He once again wrote to the Home Office, saying that although he would still be prepared to be in command in Manchester on the day of the meeting if it was thought really necessary, he had absolute confidence in his deputy commander, Lieutenant Colonel Guy L’Estrange.

The Meeting

The crowd that gathered in St Peter’s Field arrived in disciplined and organised contingents. Each village or chapelry was given a time and a place to meet, from where its members were to proceed to assembly points in the larger towns or townships, and from there on to Manchester. Contingents were sent from all around the region, the largest and “best dressed” of which was a group of 10,000 who had travelled from Oldham Green, comprising people from Oldham, Royton (which included a sizeable female section), Crompton, Lees, Saddleworth and Mossley. Other sizeable contingents marched from Middleton and Rochdale (6,000 strong) and Stockport (1,500-5,000 strong). Reports of the size of the crowd at the meeting vary substantially. Contemporaries estimated it from 30,000 to as many as 150,000; modern estimates are 60,000—80,000. The scholar Joyce Marlow describes the event as “The most numerous meeting that ever took place in Great Britain” and elaborates that the generally accepted figure of 60,000 would have been six per cent of the population of Lancashire, or half the population of the immediate area around Manchester.

Although some observers, such as the Rev. W. R. Hay, chairman of the Salford Quarter Sessions, claimed that “The active part of the meeting may be said to have come in wholly from the country”, others such as John Shuttleworth, a local cotton manufacturer, estimated that most were from Manchester, a view that would subsequently be supported by the casualty lists. Of the casualties whose residence was recorded, sixty-one per cent lived within a three-mile radius of the centre of Manchester. Some groups carried banners with texts like “No Corn Laws”, “Annual Parliaments”, “Universal suffrage” and “Vote By Ballot”. The first female reform societies were established in the textile areas in 1819, and women from the Manchester Female Reform Society, dressed in white, accompanied Hunt to the platform. The society’s president Mary Fildes rode in Hunt’s carriage carrying its flag. The only banner known to have survived is in Middleton Public Library; it was carried by Thomas Redford, who was injured by a yeomanry sabre. Made of green silk embossed with gold lettering, one side of the banner is inscribed “Liberty and Fraternity” and the other “Unity and Strength”.

At about noon, several hundred special constables were led onto the field. They formed two lines in the crowd a few yards apart, in an attempt to form a corridor through the crowd between the house where the magistrates were watching and the hustings, two wagons lashed together. Believing that this might be intended as the route by which the magistrates would later send their representatives to arrest the speakers, some members of the crowd pushed the wagons away from the constables, and pressed around the hustings to form a human barrier.

William Hulton, the chairman of the magistrates watching from the house on the edge of St Peter’s Field, saw the enthusiastic reception that Hunt received on his arrival at the assembly, and it encouraged him to action. He issued an arrest warrant for Henry Hunt, Joseph Johnson, John Knight, and James Moorhouse. On being handed the warrant, the Constable, Jonathan Andrews, offered his opinion that the press of the crowd surrounding the hustings would make military assistance necessary for its execution. Hulton then wrote two letters, one to Major Thomas Trafford, the commanding officer of the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry Cavalry, and the other to the overall military commander in Manchester, Lieutenant Colonel Guy L’Estrange. The contents of both notes were similar:

Sir, as chairman of the select committee of magistrates, I request you to proceed immediately to no. 6 Mount Street, where the magistrates are assembled. They consider the Civil Power wholly inadequate to preserve the peace. I have the honour, &c. Wm. Hulton.

The notes were handed to two horsemen who were standing by. The Manchester and Salford Yeomanry were stationed just a short distance away in Portland Street, and so received their note first. They immediately drew their swords and galloped towards St Peter’s Field. One trooper, in a frantic attempt to catch up, knocked down a woman in Cooper Street, causing the death of her son when he was thrown from her arms; two-year-old William Fildes was the first casualty of Peterloo.

Sixty cavalrymen of the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry, led by Captain Hugh Hornby Birley, a local factory owner, arrived at the house from where the magistrates were watching; some reports allege that they were drunk. Andrews, the Chief Constable, instructed Birley that he had an arrest warrant which he needed assistance to execute. Birley was asked to take his cavalry to the hustings to allow the speakers to be removed.

The route towards the hustings between the special constables was narrow, and as the inexperienced horses were thrust further and further into the crowd they reared and plunged as people tried to get out of their way. The arrest warrant had been given to the Deputy Constable, Joseph Nadin, who followed behind the yeomanry. As the cavalry pushed towards the speakers’ stand they became stuck in the crowd, and in panic started to hack about them with their sabres. On his arrival at the stand Nadin arrested Hunt, Johnson and a number of others, including John Tyas, the reporter from The Times.

Their mission to execute the arrest warrant having been achieved, the yeomanry set about destroying the banners and flags on the stand. According to Tyas, the yeomanry then attempted to reach flags in the crowd “cutting most indiscriminately to the right and to the left to get at them” — only then (said Tyas) were brickbats thrown at the military: “From this point the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry lost all command of temper.” From his vantage point William Hulton perceived the unfolding events as an assault on the yeomanry, and on L’Estrange’s arrival at 1:50 pm, at the head of his Hussars, he ordered them into the field to disperse the crowd with the words: “Good God, Sir, don’t you see they are attacking the Yeomanry; disperse the meeting!”

The 15th Hussars formed themselves into a line stretching across the eastern end of St Peter’s Field and charged into the crowd. At about the same time the Cheshire Yeomanry charged from the southern edge of the field. At first the crowd had some difficulty in dispersing, as the main exit route into Peter Street was blocked by the 88th Regiment of Foot, standing with bayonets fixed. One officer of the 15th Hussars was heard trying to restrain the by now out-of-control Manchester and Salford Yeomanry, who were “cutting at every one they could reach”: “For shame! For shame! Gentlemen: forbear, forbear! The people cannot get away!”

Within ten minutes the crowd had been dispersed, at the cost of eleven dead (at that time — four more died of wounds later) and more than six hundred injured. Only the wounded, their helpers, and the dead were left behind; a woman living nearby said she saw “a very great deal of blood”. For some time afterwards there was rioting in the streets, most seriously at New Cross, where troops fired on a crowd attacking a shop belonging to someone rumoured to have taken one of the women reformers’ flags as a souvenir. Peace was not restored in Manchester until the next morning, and in Stockport and Macclesfield rioting continued on the 17th. There was also a major riot in Oldham that day, during which one person was shot and wounded.

The Peterloo Massacre has been called one of the defining moments of its age. Many of those present at the massacre, including local masters, employers and owners, were horrified by the carnage. One of the casualties, the Oldham cloth-worker and ex-soldier John Lees, who died from his wounds on 9 September, had been present at the Battle of Waterloo. Shortly before his death he said to a friend that he had never been in such danger as at Peterloo: “At Waterloo there was man to man but there it was downright murder.” When news of the massacre began to spread, the population of Manchester and surrounding districts was horrified and outraged.

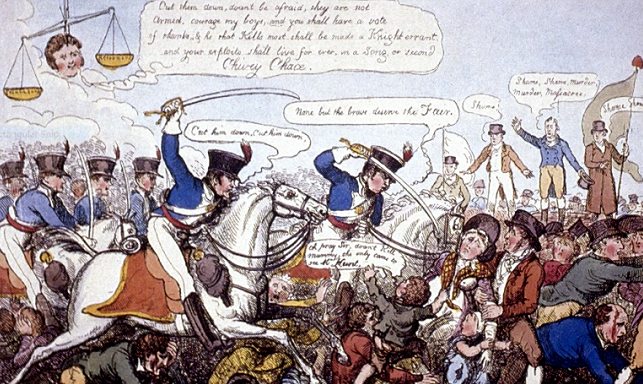

After the events at Peterloo, many commemorative items such as plates, jugs, handkerchiefs and medals were produced; they were carried by radical supporters and may also have been sold to raise money for the injured. The People’s History Museum in Manchester has one of these Peterloo handkerchiefs on display. All the mementos carried the iconic image of Peterloo; cavalrymen with swords drawn riding down and slashing at defenceless civilians. The reverse of the Peterloo medal carried a Biblical text:

‘The wicked have drawn out the sword, they have cast down the poor and needy and such as be of upright conversation.’

Peterloo was the first public meeting at which journalists from important, distant newspapers were present, and within a day or so of the event accounts were published in London, Leeds and Liverpool. The London and national papers shared the horror felt in the Manchester region, and the feeling of indignation throughout the country became intense. James Wroe, editor of The Manchester Observer was the first to describe the incident as the “Peterloo Massacre”, coining his headline by combining St Peter’s Field with the Battle of Waterloo that had taken place four years earlier. He also wrote pamphlets entitled “The Peterloo Massacre: A Faithful Narrative of the Events”. Priced at 2d each, they sold out every print run for 14 weeks and had a large national circulation. Sir Francis Burdett, a reformist MP, was jailed for three months for publishing a seditious libel.

The poet Percy Bysshe Shelley was in Italy and did not hear of the massacre until 5 September. His poem “The Masque of Anarchy”, subtitled “Written on the Occasion of the Massacre at Manchester” was sent for publication in the radical periodical The Examiner, but because of restrictions on the radical press, was not published until 1832. (See Annex)

N.B. The synopsis above is an amalgam drawn from various sources to which I am eternally grateful. The only major difference between these sources was in the numbers of the wounded. However other records indicate that many of the wounded did not report themselves as such for fear of arrest and punishment, and thus I have elected to use the upper figure of 600-700.

Message from the past

To Henry Hunt, Esq., as chairman of the meeting assembled in St. Peter’s Field, Manchester, sixteenth day of August, 1819, and to the female Reformers of Manchester and the adjacent towns who were exposed to and suffered from the wanton and fiendish attack made on them by that brutal armed force, the Manchester and Cheshire Yeomanry Cavalry, this plate is dedicated by their fellow labourer, Richard Carlile: a coloured engraving that depicts the Peterloo Massacre (military suppression of a demonstration in Manchester, England by cavalry charge on August 16, 1819 with loss of life) in Manchester, England. All the poles from which banners are flying have Phrygian caps or liberty caps on top. Not all the details strictly accord with contemporary descriptions; the banner the woman is holding should read: Female Reformers of Roynton — “Let us die like men and not be sold like slaves.”

Now, just over a year short of the Bicentenary of the Peterloo Massacre we stand on the lip of a similar abyss. Those 15 (plus one child) who were massacred and those 600-700 who were put to the sword, the hoof and the bayonet yet survived that day on St. Peter’s field were unsuspecting of the depths of brutality and outright extra-judicial execution to which the apparatchiks and enforcers of a corrupt and insular regime would sink in order to protect their sinecures and maintain their unmitigated power.

Thus, it is incumbent upon us now not to walk naked and unprepared into that same trap in the days, weeks and months ahead of us this the burning summer of our discontent.

When the law no longer protects us from those who would harm us, but protects them from us, then that is the time when all free men and women must make that most critical of decisions and ask themselves “Is this the time when we must spit on our hands, hoist the black flag, and begin to slit throats?” (With apologies to Henry Louis Mencken)

— Seneca III, on the 203rd anniversary of the Battle of Waterloo, this 18th day of June 2018

Next: Part 6B, Organising for the Present: Planning, Preparation and Execution.

Annex

The poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, upon hearing of the Peterloo Massacre, wrote ‘The Masque of Anarchy’, which was banned for thirty years until ten years after his death. The full text (all 91 verses) may be seen here, but below are a few selected verses.

“Ye who suffer woes untold,

Or to feel, or to behold

Your lost country bought and sold

With a price of blood and gold.Let a vast assembly be,

And with great solemnity

Declare with measured words that ye

Are, as God has made ye, free.Let the charged artillery drive

Till the dead air seems alive

With the clash of clanging wheels,

And the tramp of horses’ heels.Stand ye calm and resolute,

Like a forest close and mute,

With folded arms and looks which are

Weapons of unvanquished war,And that slaughter to the Nation

Shall steam up like inspiration,

Eloquent, oracular;

A volcano heard afar.Rise like Lions after slumber

In unvanquishable number,

Shake your chains to earth like dew

Which in sleep had fallen on you —

Ye are many — they are few.”

For links to previous essays by Seneca III, see the Seneca III Archives.

Research, iffen you will :

The STEN gun.

The Slam-Bang shotgun (there are many different names for essentially the same thing.

The “zip” gun.

Not difficult to make–especially the latter two– and a lot better than the proverbial sharp stick.

A fascinating story, with sobering implications. Thank you.

A portion of St Peter’s Fields later became the site of the Manchester Free Trade Hall, where, almost a century and a half after the events related above, Bob Dylan was to exhort his accompanists to ‘Play [……..] loud!’ in response to someone in the audience having called him Judas.

The irony of steadily rejecting the traditional hierarchy of governance, often on the grounds of unfair capitalisation of position or of material ownership, is that the handing of authority to elected representatives is also what has helped usher in the socialist world we now enjoy, along with big government. This seems quite obviou as part of any election cycle – promising more spending for votes, not cutting back because of loss of votes.

In the UK the decisive point must have been the Parliament Act of 1911

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parliament_Act_1911

With spending and taxation being combined into a single budget in the 1860s, so removing lords veto of specifics, the above act removed the veto of the combined budget

https://www.ukpublicrevenue.co.uk/past_revenue

shows the result, which is fine if you like socialism and government involved in everything, and I suppose it removed some of the power of the traditional elite, but I think you will find that power in the hands of others all the same, whether the mic or the frankfurt school or EU/ECB. Well at least it seems fairer?

The socialist or techno statist mindset has also produced more than its fair share of atrocity.

I am not trying to say one thing or another really, but there were also traditional virtues that went along with landowners and gentry, generally conservative values.

Here is another interesting take, bit hard to read

http://www.historyandpolicy.org/policy-papers/papers/the-1909-budget-and-the-destruction-of-the-unwritten-constitution

The unwritten constitution of monopoly of supply by the commons was not breached by the lords though – they were within their right to reject/veto that supply.

Le plus ça change…

I am put in mind of the .45 caliber Liberator pistol, dispersed to European partisans during WW2.

In this video, edited down from 31 to 14 minutes (with original interviewer Elsa’s blessing), Tommy Robinson also seems to be making a call to arms, while referencing past sacrifices by British soldiers in defense of England.

May 23, 2018: Tommy Robinson Interview Two Days Prior To His Arrest & Detention

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MR9fRa9I8SY&t=24s

Seeing Shelly’s poem, I’m spurred to repost my own effort here on this thread for posterity.

Patriots, Traitors, and Invaders

Dedicated to Tommy Robinson

Here’s a tale of Quisling traitors,

Sold their country to invaders.

The first was shot in forty-five,

But many more are still alive.

When was there a referendum,

Ere our traitors thought to send ’em?

Rivers of blood would be the cost,

Enoch was right, now Britain’s lost.

Bombs and bullets, acid and knives,

Vans on pavements destroying lives.

Showing rape gangs now forbidden,

Poor old Tommy he’s in prison,

While to jihadis flats are given,

And ISIS killers all forgiven.

Hitler’s Nazis could not manage,

What our Quislings done in damage!

If Churchill were around today,

I’m confident that he would say:

“In older and more modern time,

Treason must be capital crime,

Patriots must be supported,

And invaders all deported,

Till our girls walk unmolested,

After British metal’s tested.”

Will saving Blighty come too late,

Before the Saxon learns to hate?

If saving’s coming, it can’t wait,

Or Islam will be Britain’s fate.

*Yes, metal. Mettle without metal is futile resistance.

It will take British metal as well as mettle to win the counterjihad.

Those of us of advancing years were taught about the Peterloo massacre at school as part of the syllabus on Parliamentary reform. I doubt many school kids in the UK today know anything about it. Howard Spring in his novel ‘Fame is the Spur’ has a character who gives an account of the shameful episode in UK history. What’s important to remember is that the elites don’t change.