This is the second part in a series about sharia in Pakistan. Part I is here.

Pakistan II: The Hudood Ordinances

“Twisting the Words of God”

by Peter

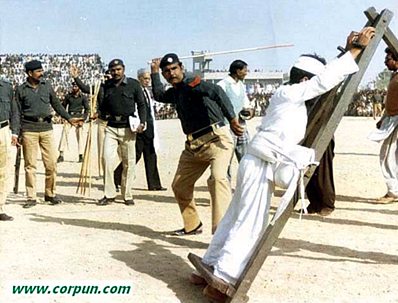

The Hudood Ordinances have been universally condemned as instruments used by the regime to oppress women and non-Muslims in Pakistan. These ordinances were passed into Pakistani law during the Presidency of Zia ul Haq to enable Sharia punishment to be imposed for theft, extramarital sex, and the consumption of alcohol. Particular condemnation has been reserved for the requirement for rape victims to produce four male witnesses to the offence, which leaves them vulnerable to prosecution themselves if they are unable to do so. According to these laws, the penalty for theft is the amputation of a hand, and for extramarital sex, death by stoning or public whipping. I’m not sure what the penalty is for the consumption of alcohol, but maybe it doesn’t matter as long as they do it in Tashkent.

These laws were welcomed at the time by hard-line Islamists, which goes a long way towards explaining why the remains of the late and unlamented General Zia ul Haq lay decomposing within the hallowed grounds of Islamabad’s Shah Faisal Mosque instead of in an ordinary cemetery with the rest of the faithful departed.

In spite of unyielding opposition from the same hard-line Islamists who welcomed the original legislation, the Ordinances were amended in 2006 by the Women’s Bill, which changed the punishment for having consensual sex outside marriage to imprisonment of up to five years plus a fine of 10,000 rupees. Rape would be punishable by 10 to 25 years of imprisonment, but with death or life imprisonment if committed by two or more persons together, while adultery would remain under the Hudood Ordinance and punishable by stoning to death. The Bill also outlaws statutory rape, i.e. sex with girls under the age of 16, but as with many things in Pakistan, persuading the police to enforce any of these laws largely depends on whether or not the accused is a Muslim.

As with Sharia, the Hudood Ordinances also discriminate against women and non-Muslims. For example, during a trial, the word of a Muslim is given more weight than that of a non-Muslim and the word of a man is given more weight than that of a woman, which explains why so many non-Muslims are being accused and convicted of blasphemy. The mere fact that they are non-Muslims leaves them vulnerable to such an accusation.

Such was the case of Gul Masih, who had been accused of blasphemy following a local dispute over a broken water pipe. The evidence was said to have been contradictory, and at best hearsay, but Gul was convicted and sentenced to death on the strength of it. The main prosecution witness was one Sajjad Hussein, of whom the judge said, “This man has a beard and the outlook of a true Muslim. I have no reason to disbelieve him.” Gul Masih was freed on appeal in 1995 and later fled to Europe after several attempts were made on his life.

The tragedy of Nageena and Ghulam Masih is another indictment of the bias and partiality of the Hudood Ordinances. Seven-year-old Nageena Masih was set upon and gang raped by four Muslim youths in her Punjabi village. The teenagers were caught in the act by Nageena’s father, Ghulam Masih, and a group of other villagers but they managed to elude capture by running across some open fields. Ghulam and his wife Shehnaz reported the incident to the police, and then took little Nageena to the nearest hospital where she was diagnosed with severe internal injuries and admitted for further examination.

In the meantime, many of the villagers had given their names to the police as witnesses and the perpetrators were arrested. In any other country but Pakistan, justice would then have taken its course, but it was not to be. The four youths were released from custody and Ghulam Masih was advised to take no further action by the local chief of police. As the victim and witnesses were Christian and the rapists were Muslim, a conviction was unlikely. However, Ghulam Masih continued to seek justice for his daughter, refusing presents and other inducements from the families of Nageena’s rapists.

Following the death of an elderly woman in suspicious circumstances, the four teenaged rapists accused Ghulam Masih of murdering her. This was impossible since, at the estimated time of death, Ghulam had been working in the fields with other villagers, all of whom bore witness to that fact, yet Ghulam was arrested and accused of a murder he could not possibly have committed. The same chief of police who released Nageena’s rapists without charge now held the victim’s father in custody and had him flogged on a daily basis because of his religion. When questioned by journalists, he stated that Ghulam Masih was a Christian while his accusers were all good Muslims so there was no reason to disbelieve them. His first duty was to Islam. He was convinced that the Courts would take a similar view and Ghulam Masih would be hanged.

Since her ordeal, little Nageena remained in a state of shock and has been unable to utter a word. Her injuries were so bad that, when last heard of, she still suffered severe abdominal pain and she would be unable to have children. From his prison cell, Ghulam Masih defiantly refused to withdraw his accusations against his daughter’s rapists, despite repeated floggings by his gaolers. Much later, Ghulam was released on bail but Nageena remained mute and her mother Shehnaz was housebound, too terrified to step outside her home.

After making many inquiries as to his fate, I was informed by the Barnabas Fund, a Christian organisation that actively ministers to persecuted Christians abroad, that the case against Ghulam Masih had been dropped, although he was still facing persecution and threats from his accusers. Nageena was now living at a secret refuge for Christian women and girls, as it was felt that she would no longer be safe with her parents.

Beating, rape, acid-throwing and burning are all common forms of domestic violence committed against women in Pakistan. Very few women ever make a formal complaint, and those that do often wish they had saved themselves the trouble as their grievances are frequently ignored, and they are ordered by the authorities to return to their violent households. There has been a disturbing increase in the incidence of acid-throwing. Although this does not normally cause the death of the victim, she can be hideously scarred and permanently disfigured as a consequence. No national statistics are available, and those that have been published have been compiled on a localised basis by human rights organisations, hospitals and women’s refuges. According to “Slogan,” a bi-monthly magazine published in Multan, 279 women in that city were recorded as having suffered severe burns from acid attacks between January and September 1991. From September to December 1992, the same publication revealed a further 269 cases.

Many families do not make formal complaints for fear of adverse publicity, and most incidents are settled out of court so that the perpetrator gets away scot-free even though the law prescribes a term of life imprisonment for anyone convicted of causing injury by throwing acid. Human rights activists in Multan are trying to restrict the sale of acid and to reinforce the law so that more offenders can be brought to trial, but there are very few convictions. Corrupt police and the lack of money, power and influence on the part of the female victims all militate against the proper dispensation of justice.

So-called “kitchen accidents” are also common in Pakistan. These are cases where women are deliberately set on fire by their husbands or by other members of his family, and the blame is put on a burst kitchen boiler or some similarly malfunctioning domestic appliance. In December 2002, the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan reported that 80% of Pakistani women were victims of ongoing domestic violence and that the burning of women was part of an endemic pattern of serial brutality. Once again, there are no reliable statistics available nationally, only reports from various women’s groups that women were being burned in Pakistan “in alarming numbers.” From 1994 to 2002, the Pakistan Progressive Women’s Association recorded over 4000 incidents of domestic burning in Islamabad and Rawalpindi alone. Another women’s refuge reported 1000 cases over a two-year period. Only one in ten of these women ever survived and only three of their attackers had ever been convicted. Domestic violence is currently the biggest single cause of injury to Pakistani women, resulting in more hospital admissions than rape or traffic accidents. Women’s groups point to the rise of Islamic fundamentalism in Pakistan since the early 1970s and the adoption of Sharia law as the primary causes of the deteriorating status of women in this country.

One well-publicised case of acid-throwing involved Bilal Khar, a former politician and the scion of one of Pakistan’s most influential families. He met and married Fakhra Yunas, a beautiful former dancing girl, but after three years of violence and abuse she left him and returned to her mother’s house in one of the poorer districts of Karachi. Five days afterwards, her husband allegedly crept into her mother’s home and, while Fakhra was sleeping, poured acid over her in a vicious act of revenge. Fakhra’s face and upper torso were horribly disfigured. Physically and psychologically scarred, she sought refuge at the home of Tehmina Durrani, who had written a best-selling book entitled My Feudal Lord about her own abusive marriage to Mustafa Khar, Bilal’s father. When Fakhra’s family filed a complaint with the Karachi police, the Khars unsuccessfully attempted to bribe them to withdraw this. The complaint still stands, but no action has successfully been brought against Bilal Khar.

Bilal was brought to trial but was acquitted on December 16, 2003 when prosecution witnesses withdrew their testimony. Meanwhile, Fakhra had relocated to Italy where, at the request of Tehmina Durrani, the Italian government arranged to care for her and her then five-year-old son Nauman . Despite 38 operations funded by a Milan-based cosmetics firm and efforts to help her lead a normal life, the pain, disfigurement and psychological anguish became too much for Fakhra to bear. On 17th March 2012 she jumped to her death from her sixth floor apartment in Rome.

In May 2014 the Sindh High Court instructed the Inspector General of the Punjabi police to produce Bilal Khar in court to face a retrial and, when he failed to appear on 29th September 2014, the Court reissued its instruction. Bilal was being held in custody for an unrelated offence and has since publicly denied the acid throwing charges. It remains to be seen whether his influential family and political connections can continue to prevent him from facing justice.

There are people in Pakistan who put their lives in danger by standing up for the rights of abused women and there are refuges where victims of domestic violence are given protection. The Pakistan Progressive Women’s Association runs a number of these, and one of the residents allowed herself to be interviewed by a British television reporter. Like Fakhra, she had been horribly scarred after her husband had set fire to her. She took him to court only to have the case dismissed by a judge, who said she was insane. When interviewed, she blamed her plight on “Men who twist the words of god to make unjust laws.”

In predominantly rural areas, Pakistani women are treated as the property of their men, either of their fathers before marriage or their husbands afterwards. In this backward society, where custom and tradition carry the force of law, female members of a family are often considered as nothing more than a commodity to be bought and sold in marriage, the woman concerned being given no say at all in what happens to her. In an increasing number of cases, some particularly gruesome things have happened arising out of two equally barbaric perceptions: the commodification of women and the concept of “honour.” A man’s honour in tribal areas is identified by three factors, “Zan, Zar and Zamin — Women, Gold and Land.” A woman is regarded as an object of marketable value, so that she is capable of being traded as a commodity, and personifies the “honour” of the man who “owns” her. That “honour” can be compromised by any imputation of sexual misconduct, either real or alleged, on the part of the woman, and the consequences to her are inevitably fatal.

Another way to bring “shame” on her family would be for a woman to object to domestic violence, to seek a divorce or, even worse, to choose her own marriage partner. I was in India early in 1998 when I began to read in the local press of an incident, which was to gain world-wide notoriety and cause riots on the streets of Karachi. On 12 February 1998 one Tariq Khan, head of the Pathan Council, announced that a sentence of death had been passed on a young woman of his tribe, Riffat Afridi, who had eloped with and married her lover, Kanwar Ahson, a member of Pakistan’s Mojahir ethnic group. The elopement provoked severe sectarian unrest in Karachi, where rampaging hordes of Pathan men took to the streets in an orgy of violence and destruction, which brought the city to a standstill, killed two by-standers and seriously injured eight others, including two policemen. After the riots had subsided, a fiercely-contested debate ensued as to whether the couple had actually eloped or whether Riffat had been abducted against her will. It made no difference to the bloodthirsty Tariq Khan.

“It doesn’t matter whether she was kidnapped or whether she went voluntarily, she will be killed,” ranted Khan, “This is against our tradition and honour.”

There then began a race against time to find the newlyweds before Riffat Afridi’s relatives got to them first and butchered them. Tariq Khan even insisted that the police should hand the couple over to him if they found them. In the end, the couple surrendered to the police and were held in protective custody. Riffat Afridi then had to go through the ordeal of appearing before the Sindh High Court to deny the kidnapping charges laid against Ahson’s family by her father. With the eyes of the world upon her, eighteen year-old Riffat arrived at the court-house in an armoured car escorted by armed riot police. In a crowded courtroom, Ahson produced a marriage certificate, the marriage was ruled valid and the charge of kidnapping was dismissed. Riffat was then whisked away from court by the police to a safe house, but no such care was taken with Ahson.

As he left the court, Ahson was shot three times and left seriously injured in the full view of the police who made no attempt to intervene. Riffat’s father was arrested briefly for the crime and then released, while Ahson remains permanently disabled as a result of the shooting. Riffat’s family subsequently offered a reward for the murder of the couple, who went into hiding while desperately seeking political asylum to enable them to escape Pakistan. Unfortunately most countries in Europe were unwilling to take them and, when they were last heard of in 2012, they had applied for asylum in the UK.

So-called “honour killings” are common in Pakistan. In the feudal society of the Pakistani village, a woman can be killed merely for being suspected of adultery. Like blasphemy, you only have to be accused to be guilty and, because of the nature of the killing, it is treated as a misdemeanour by the police, who rarely take any action at all against the killers. One husband was interviewed by a British television reporter and admitted on film that he had murdered his wife, allegedly for adultery. He said he served less than a year in prison before paying a bribe and being released. He stated, “It is a corrupt society. I paid money to get out of jail.”

As a disturbing variation on this barbaric practice, many cases of “fake” honour killings have been recorded where women have been murdered for no other reason than the personal profit of the husband or family involved. Often, a man has murdered his wife so that he can marry someone else or even extort money from an innocent man by wrongly branding him as his dead wife’s adulterous lover. Pakistani judges often treat honour-related murders with leniency and those offenders who are prosecuted at all rarely remain in prison for long.

Because of the absence of reliable national statistics, the scale of the problem has been difficult to assess and the actual number of women slaughtered in this way may never be known. In 2003 the United Nations Organisation estimated that 5000 honour killings took place worldwide, but even they admitted that this was a conservative and approximate figure. In 1999, over 1000 reports were received of women having been murdered for reasons of honour in Pakistan, but it is likely that a great many more went unreported in tribal areas. One leading activist estimated that three women a day fall victim to the culture of honour killing in Pakistan, while the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan have stated that in 1998, 888 women died as the result of honour killing in the Punjab alone. In Sindh, 132 honour killings had been reported within the first three months of 1999. In the following year 277 honour killings were recorded in the Punjab and 246 in Sindh. Women’s groups have asserted that there have probably been many, many more, but statistics are random, fragmented and far from complete. In recent years, successive Pakistani heads of state have condemned honour killings, but such statements have been seen as little more than attempts to placate foreign criticism. To date, little effort has been made to stop this practice.

Peter is an English expatriate who now lives in Thailand.

Previous posts:

| 2014 | Sep | 19 | Why I Left England’s Mean and Unpleasant Land | |||

| Oct | 5 | Pakistan I: The Blasphemy Laws |