The essay below is the latest in an occasional series by our expatriate English correspondent Peter on the history of the Socialist Left in Britain.

The Red Evolution III: The Left, The Far Left and The Hard Left:

The Long March Away From Sense and Sensibility

by Peter

Sometime towards the end of May, 1963, I joined what was then the Portsmouth West Constituency Young Socialists. This was surprising for a number of reasons, particularly since I lived within the constituency of Portsmouth South and had held no particular political convictions up until then. Also, in view of my background, I could just as easily have enrolled in the Young Conservatives, as had a number of my former school friends.

I had been brought up in an environment of Conservatism, my mother having been an active member of the Conservative Party for as long as I can remember. I also went to an independent school after being awarded a scholarship. Prior to that, had attended a Church of England Primary School, thereby ensuring my exposure to Conservatism and conformity from very early childhood. Then there was Portsmouth itself. With a population in 1963 of around 190,000 and falling, Portsmouth had more in common with older cities and towns in the North of England than with its more genteel neighbours on the South Coast.

Portsea Island, where most Portmuthians lived, was, and still is, considered to be the most densely populated area in the UK outside of London, in spite of the large areas that were bombed flat during World War II. By 1963, most damaged parts of the city had been rebuilt, although it was claimed by some that those planners, architects and building contractors involved in its reinstatement and re-development had all but ripped the heart from the city and had inflicted more destruction upon its soul than had any of the blockbusters and incendiaries used for this purpose by the Luftwaffe.

Portsmouth West constituency was a depressed working class area that contained Her Majesty’s Royal Naval Dockyard, the principal Royal Naval establishment in the UK at the time and the biggest single employer in the city. When World War II was at its height, it maintained a workforce of 27,000 but by 1963, only around 12,000 remained. Dockyard pay was known to be well below the national average, although this was offset by the fact that, even when there was no work, nobody was ever laid off and job security was guaranteed. Unfortunately for non-dockyard workers, their wage rates were often pegged by their own employers to dockyard levels, and, unlike the Dockyard workforce, they had no guarantee of job security. One way or another, nobody living within Portsmouth West Constituency was particularly well off. To the outsider, this looked like fertile ground for rampant socialism, but this was far from true. From 1945 until 1966 Portsmouth West Constituency had returned a Conservative member to Parliament and, over the same period, had participated in serially electing a Conservative-dominated local Council. To this day I cannot understand why this should have been, but it had no bearing at all on why I joined the Labour party.

Since the age of five I had been in full-time education, being infused and indoctrinated with a level of knowledge and dexterity which those in authority felt I should acquire. I had been taught how to read, write, count and calculate. I had also been taught to do all these things in Latin, French and German as well, and had left school with the required number of certificates to prove it. However, I soon realized that in spite of all the effort I had made, along with that of my teachers I still knew nothing of any consequence, except, maybe, how to win pub quizzes. For instance, it was only after taking a job with an insurance company that I found out what insurance actually was, and I knew very little of Government, Government agencies, what they did and why they did it. Joining a political party, I thought, would help me find out how things worked and fill the vast void in my awareness and understanding. I’d had enough of conservatism for the time being, and in 1963 Portsmouth, Labour was the only viable alternative.

There was an active social scene into which I was welcomed enthusiastically, so much so that I was elected Branch Treasurer the following year and married the Branch Secretary several years later. During elections we would be out in all weathers distributing leaflets, knocking on doors to get our voters out, while at other times we would go out en masse to enjoy ourselves. There were two issues that unsettled me, however. First of all, there was this attitude that if anyone had acquired any money, property or a standard of living that was a cut above the average, then they were regarded with disdain and it was assumed that they had done something dishonest or unethical to achieve it. It was never accepted that they might have earned what they had by hard work. It was the politics of envy, and it was pervasive. It affected the older people most, the members of the Constituency Labour Party. They were real class warriors and hated Conservatives and Conservatism with a vehemence you could almost taste. They blamed the Conservatives for every possible ill that befell them, some even attributing the bad winter of 1963 to divine retribution for something the ruling Conservative Government had done. There was also a great deal of bitching and backbiting throughout the local party, which led me to conclude that, aside from the Conservatives, they didn’t like each other very much either.

In those days I had no idea who Trotsky might have been or that his views were well-supported in some circles, but this would change. There were also people outside Portsmouth who thought that Portsmouth West Young Socialists were insufficiently radical and sent one of their apparatchiks to try to inspire us and guide us towards a more leftist path. His name was Ivan, and he turned up and spoke at several of our meetings, but failed to make any impact. All I remember about him apart from his fluent babble, duffle coat and pink-tinted spectacles was his opinion about crime. According to him, there was no such thing as a criminal, only a person who was socially maladjusted and therefore should not be punished but re-educated. We treated this view with complete indifference and after a little while he went back to where he’d come from and we never saw him again. This was my first contact with anyone from the far left.

Our other bête noire was a monthly newspaper called “Keep Left”. Our own monthly newspaper entitled “New Advance” was produced nationally by the Labour Party and distributed free to all YS members. “Keep Left,” on the other hand, was one of a number of fringe publications and had nothing to do with the Labour Party, something our resident Political Agent made very clear. We were sent two dozen copies of “Keep Left” on one occasion, but sent them back. We then started to receive demands for money, and we sent those back as well. “Keep Left” supported a far-left body called the Socialist Labour League, and I shall say more about them later. There was a particularly inflammatory article authored by one Roger Rosewell that appeared to incite hooligan gangs to attack the police, something with which our law-abiding membership strongly disagreed. Some members of the branch felt that we should invite Rosewell to one of our meetings, not necessarily to explain himself but certainly to put his point of view. After he had accepted our invitation and agreed a date, I was asked not to attend as my anti-communist views were well known by then and I was unlikely to be very sympathetic.

We were well aware of what Communism was, as we all remembered how the Russian tanks had brutally crushed the Hungarian people’s uprising in 1956. Also, there were many survivors of the gulag who had made their way to the UK. Having done so, they sold their stories of imprisonment and brutal treatment at the hands of the Soviet authorities to the popular Sunday press who gave them a lot of space and, presumably, a lot of money as well. It was around this time that I decided that I had no place in a socialist movement, a view that a number of our members had already reached after I had written several letters to our local paper criticizing Labour support for Unilateral Nuclear Disarmament, increased welfare payments and comprehensive education. A number of people I didn’t like very much stopped speaking to me around this period, something I regarded as an unsought bonus.

As requested, when Roger Rosewell was due to speak at our meeting, I took my partner, the Branch Secretary, to the cinema while other Branch members awaited the arrival of their guest speaker, but he did not show. He did arrive later, however, and the meeting re-convened in the lounge bar of the nearby White Hart public house and went on till closing time. It would not be accurate to say that Rosewell held his audience spellbound. Most of them were thunderstruck by what they heard and when I saw them again the following week, they had still not recovered from the shock. The general conclusion was that Rosewell was a complete nutcase who thought that the UK was a police state and that the people should rise up against it. Most people thought he should not be taken seriously, a position supported by our Political Agent particularly, as “Keep Left” had been proscribed by the Labour Party as far back as 1958.

I never got to meet Roger Rosewell, although his name did crop up from time to time. I managed to find a few of his articles written in the early 1970s on various leftist websites and a reference on another to the “odious Roger Rosewell.” The last I heard of him was in the mid-1990s when I was working as a contractor at a South London Borough. A far-left work colleague told me that Rosewell had set himself up as a consultant to support and advise organisations that had been infiltrated by leftist agitators and strike-mongers.

It was not until the late 1960’s and early ’70s that I encountered the activities of what I call the Hard Left, the strike-mongers and the hard-core political agitators, but again, I had no direct contact with them. By this time, I had joined West Sussex County Council in nearby Chichester as a Committee Clerk and married the afore-mentioned Branch Secretary. Unlike Portsmouth, Chichester was a small County Town with a population of around 30,000 at the time. This number tended to swell significantly during the working day as the workforce commuted from surrounding towns and villages — as I did from Portsmouth.

County Hall itself was a bit of a curiosity. Someone once asked how many people actually worked there and was told “about half of them,” which, I’d say was something of an overstatement. Many of those employed by the County Council were either retired service or police personnel, and they had a monumental attitude problem. Their highly-structured service or police background led them to believe that no-one under the age of 30 was entitled to an opinion, and no-one under 40 was entitled to express one. They also took the collective view that, as they had done their bit for their country, now their country should do its bit for them. They used this approach as an excuse for doing very little in the way of work, and the powers that be also used it to justify chronic levels of overstaffing.

I did not have enough committee work to occupy me, so I looked around for other things to do. Firstly, I joined the team of County News, the Council’s own newspaper and then became the editor of Focus, the local trade union magazine which appeared whenever I had enough material to publish it. The trade union was the National and Local Government Officers Association (NALGO) and its membership in Chichester was somewhere between passive and comatose — which was only to be expected from a traditional Conservative Council, unlike the rest of the country where labour relations in what were euphemistically called the manufacturing industries were approaching anarchy. Indeed, there were so many strikes and stoppages by the various labour forces that the media and other commentators had difficulty keeping up. Needless to say, there were no strikes in County Hall, and if there had been, it is doubtful whether anyone would have noticed. One commentator who did manage to keep up with industrial relations was the celebrated Irish correspondent and broadcaster Vincent Hanna, who wrote a weekly column in the Sunday Times in which he included a detailed report on as many of the strikes, walkouts and disputes as could be covered in a week. I used to copy these religiously with suitable accreditation and include them in the current edition of Focus.

What follows is an extract from notes I reproduced from Vincent Hanna’s columns from 26th September to 31st October 1970. They are by no means complete, and are included to provide the reader with a flavor of the chaotic situation into which our country had descended.

National tin plate supplies threatened by a strike at two British Steel Corporation plants in South Wales. 23,000 tons of steel worth 1.6 million pounds affected by this walkout by 450 union members causing a further 3000 workers to be laid off… 3000 dock workers at Hull brought the port to a halt over a manning dispute… Rover cars lost 650,000 pounds due to unofficial stoppages by component cleaners and truck drivers… At Ford’s Halewood Plant, 2000 workers have stopped making gearboxes over the dismissal of one worker… 270,000 Vauxhall workers demand an extra 12 pounds a week while Ford workers want 10 pounds a week… strike by 250 maintenance engineers at Ferrodo demanding an extra 10 pounds a week causing 1000 other workers to be laid off… Walkout by 1000 assembly workers at British Leyland works, Cowley, affecting 2000 others and stopping the production of 4000 Austin and Morris cars… Lightning strikes at Mersey Docks… There were many, many more.

Harold Wilson led two Labour administrations from 1964 through to 1970 and, as they received most of their funding from the Trades Union movement, they were clearly caught between a rock and a hard place. If they were perceived to be too heavy-handed, they would antagonize their union paymasters, but being seen to be doing too little would cost them the 1970 General Election — as indeed it did, but they tried.

Barbara Castle, Wilson’s Secretary of State for Employment and Productivity, drew up a Government White Paper proposing, inter alia, compulsory strike ballots prior to strike action and the establishment of an industrial board to enforce settlements of disputes. Entitled In Place of Strife, the document divided Wilson’s cabinet and upset the rank and file Trades Unionists who by now were not going to be told to do anything by anybody. Mrs Castle was a very powerful speaker, and I was present when she addressed the Nalgo Annual Conference in Brighton in the summer of 1969 informing those present that In Place of Strife would become law, it would be robustly enforced, and nobody would prevent this.

The proposals were withdrawn three days later and Wilson’s government fell the following year.

Edward Heath’s 1970-1974 Conservative Government fared no better, although Robert Carr, Heath’s Secretary of State for Employment, did manage to get his proposals enacted. The Industrial Relations Act, 1971, balanced the introduction of compensation for unfair dismissal with curbs on the freedom to strike, but the Trades Unions’ reaction was predictable. First of all, the Trades Union Congress launched a nationwide “Kill the Bill” campaign with a march through London on 12 January 1971. This was followed two months later by a one-day strike by 1,500,000 members of the Amalgamated Engineering Union. Then matters got worse as the larger unions refused to comply with the legislation, and the Communist-led Mineworkers and Power Workers got into the act so that, by the 1974 General Election, most of the country was on a three-day week, domestic refuse lay uncollected in the streets, there were long queues at many petrol stations and Heath was on his way out. Wilson was returned to office on the basis of a commitment that he would get the mineworkers back to work and he did so by caving in to their demands. This led to more industrial anarchy including the infamous “Winter of Discontent,” a situation which was only brought to heel by Margaret Thatcher’s programme of draconian measures in the early 1980s.

On a more positive note, the requirement that strike action could only take place after a trade union ballot would ultimately be included in the Trade Union and Labour Relations (Consolidation) Act 1992 but that was twenty years away. In the meantime, the 1970s continued to be dominated by strikes and stoppages, trades union leaders regularly attended meetings at 10 Downing Street where, if stories in the press are to be believed, they indulged in copious amounts of beer and sandwiches and the economy plummeted precariously. By the time Wilson’s successor James Callaghan took his government into the 1978 General Election, Great Britain was generally referred to by its European partners as “the sick man of Europe”, and with good reason. The various 1970s Labour administrations, whilst talking tough, had been reluctant to confront their Trades Union paymasters, while from 1970 to 1974, Heath’s Conservatives had shown themselves to be a party in chaos. To be fair to the politicians, the Trades Union Congress itself was equally inept, particularly when it came to the unofficial, instant walkouts, which were on the rise. Elements in the labour force were out of control, the British electorate wanted change, and in 1978 it got Margaret Thatcher.

When Edward Heath went to the polls in 1974, he did so behind the slogan “Who runs the Country?” and he lost. It was clear by then that striking workers were exerting a disproportionate influence on the Government, the economy and on the daily lives of all of us. It was as if a hidden hand were manipulating what was happening behind the scenes, but to whom did that hand belong? From 1966 onwards, Harold Wilson was adamant that it belonged to the Communist Party of Great Britain, but I could not see how such a small, insignificant group could be responsible for so much disruption, at least not then. There were many rumours circulating of professional strike-mongers and “Union Wreckers”. Something was clearly afoot, although it wasn’t until 1992 that I found out for certain what it was and was able to piece together what had been going on.

I was on holiday in Hungary at the time and I got to talking to this man who turned up at the hotel where I was staying with a coach party of package tourists. He introduced himself as Eric and during the conversation and over the course of many others he explained that he had been employed to travel throughout the UK stirring up trouble in the manufacturing industries. Originally, he had been a member of the Communist Party of Great Britain, who sent him to most of the factories in the West Midlands and then he went to Liverpool and joined the Socialist Labour League, whom he regarded as “bloody serious revolutionaries.”

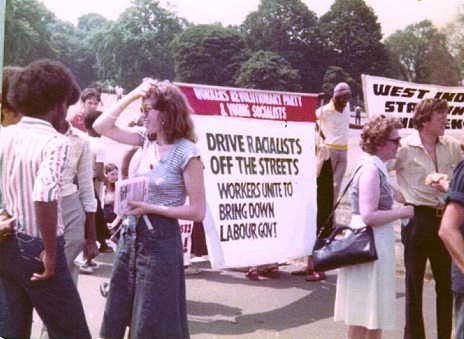

Led by a Galway-born firebrand by the name of Gerry Healy, the Socialist Labour League planned to close the docks on Merseyside, target the Ford and Vauxhall plants in the same area before hitting their factories down south. They planned a systematic assault on the car works in Oxford and the West Midlands before setting their sights on the public services and the universities. Eric told me that the Socialist Labour League were convinced that if they could bring production to a standstill, reduce the country to anarchy, they could seize power. It wasn’t the first time I’d heard something like this. I’d overheard Socialist Workers Party members saying the same sort of thing, but it was just loose talk, and I paid it no attention. I knew that if push came to shove, they couldn’t organise an assignation in a brothel. While they were adept at hijacking protest marches — with some of them even managing to wave banners, chant slogans and walk at the same time without causing themselves damage — they couldn’t run a bath, never mind a country.

Thomas Gerard (Gerry) Healy joined the Communist Party in 1928 at the age of fourteen, but eight years later he was branded a “Trotskyist” and expelled. This accusation was absurd, as up until then, Healey had never read a word of Trotsky. A year later, all that had changed and he joined the Trotskyist movement, becoming its UK leader by the end of the 1940s. He then disappeared into the covens of the faithful, indulging in various internecine disputes over the finer points of the gospel according to Marx and Lenin before re-emerging as the leader of the Socialist Labour League and, ultimately, the Workers Revolutionary Party. The latter styled itself as the world’s foremost Trotskyist Party in spite of its “Celebrity Left” reputation, due to the involvement of certain members of the Redgrave family. I often saw WRP members distributing their literature at various rallies in support of the miners in the early ’90s, when John Major’s Conservative Government was threatening substantial pit closures. They were nothing special, just as bland, boring and insignificant and having no more impact on proceedings than the Socialist Workers Party, Militant or the Revolutionary Communist Party — at least the Class War people were funny.

There was much anecdotal evidence of the participation of Communists in the various disputes, but very little proof of the scale of their involvement. I know that in the years immediately after the Second World War, the Communist Party of Great Britain attracted a great deal of sympathy and support arising from our wartime alliance with the Soviet Union. Much of this support came from within the Trade Union movement, where, during the late ’1940s, the CPGB had become increasingly involved in strikes, causing much anger and irritation to Clement Attlee’s Labour Government. However, in 1955 the Intelligence Services managed to obtain the secret membership records of the CPGB and from then on, the authorities became aware of every single operational party member and their activities were closely monitored.

Armed with information provided by this source, Harold Wilson was able to claim that the 1966 strike by the National Union of Seamen had been engineered by a “tightly knit group of politically motivated men.” He did not need to use the word “Communist” as everyone knew exactly what he meant. He then went on to name the people concerned and to make specific allegations against each and every one of them. He stated that, unlike the major political parties, the Communist party possessed “an efficient and disciplined industrial apparatus controlled from Communist Party headquarters and there was no major strike anywhere in the country or in any sector of industry in which this apparatus failed to concern itself.”

The seamen’s strike crumbled shortly afterwards. Certain left-wing commentators took the view that Wilson had deliberately smeared the strikers with unsubstantiated accusations in order to break the strike, but the Prime Minister himself had been satisfied with the accuracy of the information. Indeed, by 1968 Wilson was firmly convinced that many of the strikes and stoppages that were taking place at that time had been stirred up by militant shop stewards who, if they were not actually Communist Party members, were certainly fellow travellers or far-left extremists, more interested in destroying the national economy than representing the interests of their trade union members, people like Eric, in fact.

To make matters worse, in the late 1960s, two Czechoslovakian defectors identified a number of trade union leaders and three Labour Members of Parliament as Soviet agents. MI5 found there was some truth in the allegations, and in 1970, Will Owen was prosecuted for passing material to Czechoslovakian agents in return for cash. Unbelievably, while the case was proven, he was acquitted because the intelligence he had been passing had not been classified. Tom Driberg also admitted passing secrets to the Czechs for money but no formal action was ever taken against him. As part of the same investigation, MI5 interviewed John Stonehouse, but he denied all allegations and the matter was not pursued. Stonehouse was later gaoled for fraud after faking his own suicide.

Wilson’s critics accused him of paranoia, but he could hardly be blamed, since — if rumours are to be believed — there were many plots against his Government. I found references to one of these in two separate sources citing the Daily Mirror tycoon Cecil King and a conspiracy to supersede the Wilson Government with a cross-party coalition led by Lord Louis Mountbatten. As the story goes, the celebrated scholar Sir Solly Zuckermann, who was present at Mountbatten’s Knightsbridge flat at the time King put forward his ludicrous proposition, urged Lord Louis to have nothing to do with it and his Lordship heeded the academic’s advice. But the damage done to the British Establishment by traitors such as Burgess, Maclean, Philby and Blunt ran deep. Stories of Communist infiltration of the Trades Unions and even the Government itself would not go away, and resulted in a great deal of scare-mongering and hysteria. In 1971 MI5 estimated that there were in excess of 450 Russian spies operating in London alone, a figure that was subsequently confirmed by a Russian defector, and which prompted Sir Alec Douglas-Home, the Conservative Foreign Secretary, to expel 105 Soviet Embassy staff in September of that year. By then, the point had been reached where every major strike that occurred was being attributed to the activities of Moscow-trained agitators, but I remain unconvinced.

While Communist Party members had indeed been active at the core of the British trade union movement, particularly during the 1960’s, there is no discernible evidence to indicate either how many of them there were or how disruptive they had been. In any event, much of their activity would have been consigned to instant failure, since in trying to harness the hard left to undermine our country’s manufacturing industry, the CPGB greatly overestimated the capability of those they chose to perform that task. In particular, they failed to appreciate the fact that the Left in the UK has always been a fragmented and disparate mass of warring factions whose hatred of each other often runs far deeper than their collective hatred of capitalism, democracy or the West. Whatever mischief these people might have inflicted upon our country, their activities should not be viewed in isolation, or should any success they might have claimed.

As far as labour relations in the UK were concerned, there was far more to the industrial anarchy and disruption than could ever have been caused by a few hundred trots, commies and all-purpose loonies. Since 1945, the entire British Economy had been in severe difficulties. There had been long-term balance of trade problems, painfully slow economic growth and the pound had been de-valued several times. British industries were under-capitalised, productivity levels were so low that they barely existed and we were losing markets abroad to foreign competitors, while those same foreign competitors were making severe inroads into our own markets at home. Annual inflation rose from 4% in 1966 to around 25% in 1975 in spite of various incomes policies designed to prevent this from happening. Over the same period, trades unions, especially at shop floor level, were accusing the Government of shoring up capitalism at the expense of the working classes. The unions were becoming increasingly militant so that over-manning, restrictive practices, opposition to change and unrelenting wage demands became the order of the day. In short, as the recently-deceased Labour MP Gerald Kaufman said afterwards, the UK was a veritable adventure playground for any home-grown opportunist determined to make mischief. Any outside help they might have received was just a bonus.

I remember that there were disputes in the Liverpool docks in 1970 and again in 1971. The former was a straightforward wage dispute which was allowed to escalate just short of a general strike by confrontational negotiators on both sides and an incompetent government. The 1972 strike became a rearguard action by the dock workers attempting to prevent the introduction of containers, a fundamental change in their working conditions which would render established methods obsolete and many of their workforce redundant. They were fighting for their livelihoods but, once again, there was no evidence to suggest this was anything other than a legitimate cause rather than a fabricated dispute brought about by left-wing agitators. Any involvement by Gerry Healy or the Socialist Labour League never made the newspapers, which tends to call into question Eric’s claim that this person was a viable threat to national security. It is possible that the Socialist Labour League did aspire to take over the country by undemocratic means — most far left organisations suffer from similar self-delusion — but the fact that none of them has ever succeeded speaks for itself.

I put Eric’s grandiose claims on behalf of the Socialist Labour League down to the vanity of the far left, or the hard left, call it what you will, which has always exaggerated its own importance. At the time of Margaret Thatcher’s removal from office, members of the Socialist Workers Party were telling anyone who would listen that it was “their” campaign against the poll tax that brought her down. Later they simplified this preposterous assertion to merely claim that it was they who had brought about her downfall. Around the same time, the Revolutionary Communist Party brought out a pamphlet called “Preparing for Power.” I wonder what planet they’re on now. They were virtually bankrupted in the 1990’s over a libel suit against their magazine Living Marxism — or should that be “Lying Marxism?” — and I don’t see them about any more, not that I’ve been looking very hard.

As for Gerry Healy, he died on 14th December 1989 in obscurity and disgrace, having been expelled from the Workers Revolutionary Party for gross misconduct and sexual impropriety four years earlier. John Lister, a one-time associate, who had also been expelled from the WRP, described Healy as follows:

“Healy was a crook and a political charlatan, who preserved his position as General Secretary of the WRP by resorting to the most bureaucratic and anti-democratic measures, who stubbornly opposed any campaigning for women’s liberation or gay rights, who habitually subjected women ‘comrades’ to sexual abuse, who sold out the WRP’s formal principles and programme for Middle East oil money and who has done more than anyone to degrade the reputation of Marxism and Trotskyism in Britain”

Upon Healy’s expulsion, The Workers Revolutionary Party imploded into a number of irrelevant, Trotskyite clusters, thereby ceasing to have any significance, even in the twilight zone that is hard-left politics.

To be continued

References:

- Political Strikes: The state of Trades Unionism in Britain — Peter Hain

- Spycatcher — Peter Wright

- Friends in High Places — Jeremy Paxman

- The Labour Government: 1964 to 1970 — Harold Wilson

- Gerry Healy: A Revolutionary Life — Corrinna Lotz and Paul Feldman

Peter is an English expatriate who now lives in Thailand.

Previous posts:

I wonder how much of those Socialist movements were being indirectly funded by the Establishment and other assorted Globalists with planned goals over 20-30 or more years in which to achieve those goals.

I have no doubt that Britain’s signing onto the European Economic Community was one of those goals.

From the information you have supplied it appears that M15 was also in on the Globalist agenda – why are they still in existence now I wonder, if at that time in which you refer, they could not bring to justice or even light, exactly who was doing what and for what reason to the workers and their employers?

Hindsight can be a valuable tool in sorting through the many layers of subterfuge and sabotage, in this case, the deliberate collapsing of Britain’s manufacturing base to achieve certain political outcomes.

A good and enlightening article.

Well, MI5 (or something like it) is necessary. For American readers, it’s roughly equivalent to the FBI, ie it deals with internal security; MI6 is concerned with external security, like the CIA.

I’m not suggesting it is not necessary, what I am suggesting is that MI5 is no longer being used for the original purpose it was intended and is now being used as a government agency to control the internal functions of the Globalist agenda, and has been used as such for decades.

My theory is that such movements have various sources of funding.

The USSR was definitely one in the old days.

Currently, I suspect that Russians, Saudis, Iranians and Chinese are behind a lot of these things, as attempts to undermine Western societies.

Obviously a lot is channelled through Soros. He may be behind some of it directly, but I suspect that there are other interests involved, as well.

I suspect that a lot of these interests enjoy doing what the Tsarist secret police did, and stoking rumours that “It’s the Joos!” in order to push attention away from themselves.

I will add that, in fairness, I do think that a lot of corresponding movements in Russia have Western funding, also.

Peter’s description of the RN Dockyard Portsmouth reminds me of a little ditty we used to sing when I was stationed at Eastney (RM) Barracks on Portsea Island about two and half miles from the Dockyard:

The Dockyard matey’s children, sitting on the Dockyard wall,

Just like their fathers, doing sod all.

And when they grow up, they’ll be Dockyard matey’s too,

Just like their fathers, sod all to do…

…and other highly inappropriate verses that I can no longer remember.

(‘Matey’ is local slang for a civilian dockyard worker and ‘sod’ is not the actual word used at the time but this is a family blog after all ?)

As a young Midshipman fresh out the packet, we were given a tour of Pompey dockyard. There was no work going on except where women were sewing flags where it was busy busy.

The women were on piece work, they only got paid for finished products….

The men were unionised, the women were not and nobody cared about them.

Hey, MC, you were a Snotty! How are things now – long retired and totally p****d off with the way things are going now just like me?

Nothing’s been the same since the bean counters did away with the Tot. Illegitimate the lot of ‘em, and keel-hauling would be too good for them ?

Seneca, I didn’t realise you were a bootneck. I lived just down the road from Eastney Barracks and Joined the Royal Marine Cadets at an early age. I was taught to box by one Colour Sergeant South. This ultimately got me to two Southern Counties ABA semi finals before I discovered women and everything went downhill.

I think you made the correct ‘downhill’ decision, Peter ??

A fascinating and erudite post, Peter. As you may know, after WW2 the British reorganised the Trades Unions in West Germany, and insisted on no more than one union per employer, leading to far fewer strikes than here in the UK.

On a lighter note, during the “Winter of Discontent”, when rubbish was not being collected, many emergency deposit areas were brought into use, including the churchyard of St Anne’s, Soho in central London. Some wag graffitoed (is that the word?) on one of the posters on the fence, “Come unto me, all ye that are heavy laden”.

I didn’t intend to be anonymous there!

Hi Mark, hope you are well.

A fascinating and well-written article.

The original high-quality content on GoV is really impressive.

I second that! Educational as well as very well-written and easy to read!