Spring Fundraiser 2015, Day Four

Today is the fourth day of our week-long bleg.

The response has been overwhelming so far — I can tell by how far behind I’ve gotten in my thank-you notes. There are just too many to write in any given day. Our readers seem absolutely determined to keep us afloat.

It’s difficult to find words to express our gratitude for your gifts. In fact, it’s hard to find new adjectives at all. I’ve used up all the superlatives I could think of, and I hate to be repetitive.

It’s difficult to find words to express our gratitude for your gifts. In fact, it’s hard to find new adjectives at all. I’ve used up all the superlatives I could think of, and I hate to be repetitive.

So I’ll just say: Thank you!

The theme of this week’s bleg is “Stories”. Tonight’s story (really, a group of stories) concerns one of the careers — the central one, from my perspective — that I pursued before I started blogging the Counterjihad.

For more than thirty years I was a landscape artist, beginning in the mid-1970s, but with an interlude as a programmer for a while in the late ’70s to save up for another stint. Eventually I quit my job and moved out here, and continued painting for another twenty-seven years.

I started keeping a log of my work after my first show, so I know I painted between 400 and 500 paintings during that time. That’s a lot of paintings, and though I never really forget any of them, some of them do slip out of my mind for a time. When I encounter one on somebody’s wall after not seeing it for several decades, I’m brought up short: Oh, yes! I remember the day I painted that one! How hot it was, and how many mosquitoes were biting me…

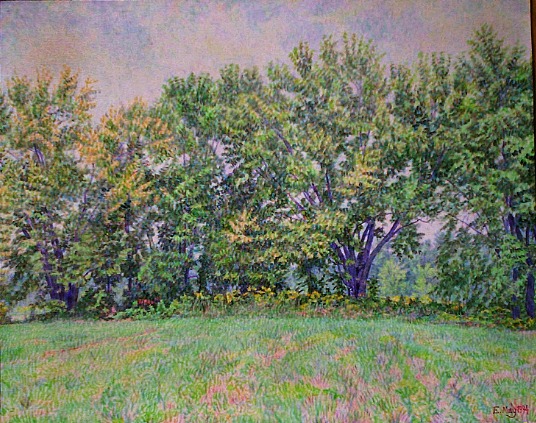

The general rule in those years was that the paintings I liked the most were the ones that other people didn’t particularly care for. The one below, for example: it was painted down on the flood plain by the river in September 1994. I hauled it outside today to take a photo of it, and then processed the image as best I could to make the colors look right. After twenty years the varnish has yellowed a bit, but this version is not too bad:

It satisfies me in ways I can’t explain — when I look at it, I smile, remembering those muggy days down by the river, the thunderstorms, the way the vegetation smelled. You could see the yellow coming in early on the trees, as often happens with river maples after a dry summer. The distant line of trees could be glimpsed through a row of maples and choke cherries. The tickseed sunflowers and the Jerusalem artichokes had started to bloom, and the last of the Joe Pye weed blossoms can be seen in the shadows to the left, under the tree.

This painting never showed any signs of selling, so after a couple of years I took it off the market. It hung in my office at work (after Dymphna became ill, I took up programming again) for a few years, and then after I got laid off, it moved up to the Eyrie here in Schloss Bodissey to keep me company in my office.

The next painting was much more popular, and serves as a good example of the type of work customers prefer. It shows Dymphna’s herb bed on the south side of our house in July of 2003. It was the fifth and final version of the same scene, part of a series that continued for about ten years.

In it you can see lavender (left foreground), an ornamental cherry (left background, now much bigger), bee balm (purple flowers in the back), oregano (mid-foreground), cone flowers (mid-background), basil growing in the pot, Rudbeckia or black-eyed susans (middle right foreground), vitex (a blue-flowering shrub in the right background, now grown into a ridiculously large tree). The daylilies on the right had finished blooming.

I remember those days well, too. My eyes had deteriorated quite a bit by then, and I tended to stay closer to home and sit in the shade when I could.

The paintings most meaningful to me are another matter. They don’t include the ones I sold for more than $1000 — there were only a handful of those, anyway. And they’re not necessarily my best efforts, artistically speaking. What gave them great meaning for me was what they meant to someone else.

The first one was painted in the earliest days of my free-lance poverty. I stayed on in Williamsburg for a while after I graduated, and painted pictures here and there, selling them where I could (and never for more than $50).

One day in March of 1974 I was sitting on the green painting a picture of one of the restored buildings in Colonial Williamsburg. That’s the painting shown at the top of this post; you can see the subject of the painting in the background, and a little bit of the painting itself.

While I was painting, a couple of Catholic priests came by. They had brought a large group of middle-school boys to see the colonial sights, and stopped by to see what I was doing. They were enthusiastic about the painting, and wanted to see it when it was done. I was working in acrylics, which meant that the paint dried very quickly. I asked them to come back in half an hour to see the finished product.

When they came back they were delighted with the painting, and asked me how much I wanted for it. I suggested $40, if they could swing it. They pooled what money they could dig out of their pockets and just barely managed to scrape the total together, most of it in ones. They had no spending money left, but they carried the painting off with them, and were happy.

Now, that was a meaningful painting.

And $40 was a lot of money in those days. I could live off that for couple of weeks.

The next example was in the early 1980s, not too long after I moved out here. I was painting a landscape down by the river, and an old man stopped by to watch me working. He told me that he had had a vision of the Pearly Gates in a dream, and wondered: could I paint them for him? I replied that I could try, if he could provide a fairly good description. He said that he would make a little sketch and bring to my house. I gave him our address.

He didn’t drive, so when he showed up at our house a few days later, his son was with him. The old man had a piece of notebook paper with a crude drawing of the shape of the Pearly Gates. He described the golden color, and the way the light looked, and some other details of ornamentation and so on. He said he knew he wasn’t going to live much longer, and God had shown him what he would see when he reached the other side.

I don’t remember what price I named, but it was fairly low — I could tell the family was not well-off. I worked on the painting for a week or two, and the son brought him to get it when it was done. The old man was very happy; there might even have been tears in his eyes. He turned to me and said, “That’s it. That’s exactly what I saw.”

After he paid me and left, I never saw him again.

Now, that was a meaningful painting.

The final example of meaning concerns a drawing, rather than a painting. In the early 2000s a couple who live not far from us were struck with tragedy when their 18-year-old son died, killed in a car crash. No alcohol was involved — the inattentive teenage driver had been changing the radio station or something, and lost control of the car. Their son was a passenger, and as is so often the case in such accidents, he had not been wearing his seatbelt. He had been the apple of his daddy’s eye, and Wayne was heartbroken.

A few weeks after the funeral, Wayne and his wife called and asked if they could come visit us to show me how they’d like me to help them with their son’s gravestone. Dymphna and I already knew them both: Wayne had done electrical work for us years ago, and his wife was the granddaughter of a woman at our church.

They showed up with some notes and photographs. They wanted an engraved image on the permanent stone marker, one that would combine some of their son’s favorite activities. Wayne Jr. had been an avid four-wheeler, and they brought photos of his vehicle (I remember it had big tires). He used to ride it down to the pond across the road and go fishing, and they brought photos of the pond. They wanted the picture to show the four-wheeler by the pond, and there were certain features in the surrounding landscape that needed to be included.

I drove down to their place and took a look at the scene by the pond, to get a better feeling for what I had to do. Then I went home and started a series of drawings, carefully reproducing the four-wheeler and sketching in the background. The final result was a large pen-and-ink drawing that included all the elements they had requested. When I delivered it to them, there was no charge, of course — I offered my work in memory of Wayne Jr.

The monument company was able to use modern electronic methods and scan the drawing before etching the stone, so that most of the image transfer could be accomplished by automated means. Wayne and his wife invited us to the dedication ceremony when the stone was laid in place over the grave. She was in tears, but happy with the final result. She said it helped ease her grieving heart.

Now, that was a meaningful drawing.

The above anecdotes illustrate the different meanings I drew from all those decades of painting. For years after I had to quit, I avoided remembering those times, because it hurt my heart so much not to be painting anymore. But enough time has gone by now, and I can look back on it as something from long ago.

I knew I was over-clocking my eyes when I did all that. When I went out in the glare of the sun every day for years. When I stared off into the distance at the shimmering horizon. When I looked at the bright white canvas as colors gradually appeared on it.

I wore my eyes out early. I knew that’s what was happening, but I did it anyway, because it was the work the Lord had called me to do. It was worth it.

What I had always wanted to do was to learn how to see. I just had to keep practicing until I could finally see properly. My painter’s prayer was: Lord, give me clear sight, and the wits to copy it right.

And by the time my eyes went bad, my prayer had been answered: I knew what I was doing.

Wednesday’s generosity flowed in from these places:

Stateside: California, Florida, Illinois, Massachusetts, Michigan, Vermont, and Virginia

Near Abroad: Canada

Far Abroad: Australia, Croatia, Denmark, Germany, India, and the Netherlands.

Thanks very much to everyone who donated. Individual thank-yous will be coming soon.

The tip jar in the text above is just for decoration. To donate, click the tin cup on our sidebar, or the donate button, on the main page. If you prefer a monthly subscription, click the “subscribe” button.

Somehow, from those two pictures and your description, I imagine that your use of bright, vivid colors was a characteristic tendency which attracted people more than the crisp, true lines and details in the shadows. Perhaps there’s a parable in there somewhere, though I wouldn’t presume to know.

I’ve also learned to be cautious about believing that images (particularly the most beautiful) can be reproduced in their full depth of color and presence by existing technological means. I once commented, immediately before seeing a special presentation of Van Gogh’s work, that the idea of irreproducible unique value in the paintings of masters was largely a social construct (or some words to that effect), and that seeing the paintings in person was an exercise in snobbery because it was necessarily a somewhat exclusive experience, since it was simply not possible that everyone COULD see the originals with their own eyes. I ate those words fairly quickly. I still believe that there are painters in our day who can create work equal to that of any old master (though certainly fewer than there might be if the art world didn’t make a fetish of celebrating barbarism, ugliness, and the decline of Western Civilization), but our technology can’t reproduce the originals with the degree of fidelity necessary to capture their true greatness, and those who can create new art have better things to do than make copies of the old (though certainly it can be an invaluable learning tool).

The colors that do come through my monitor suggest that your paintings would be something to see in person, both in sunlight and in shadows, and oft times betwixt. I shan’t regret the infirmities that make that presently impossible, they were come by honestly enough. But of the things in this world I should be pleased to see with my own eyes, I think they’d be counted.

If he has time I hope he tells you a bit of his working theories regarding the placement of color – or rather how he placed hues in conjunction with one another. I’m not expressing it well, though I have lived with the results for our whole life together.

His painting of water was particularly instructive…people were drawn to those to try to understand how he did it. He might say he was just illustrating the interference patterns of fluids, or some such.

If you lived with one of his paintings, it changed the way you saw the physical world. As one person said, “he makes you see the distance differently”. I think she meant that the painting she bought caused her to *notice* the difference for the first time.

We still have several that are vibrant even in my memory. The B spent a lot of time on “the low grounds” – the flood plain near the river. He always got permission from the owners before he trekked in to set up his canvas. For this one, the land belonged to Martin, who’d long ago given a kind of permanent permission for his work.

In one case, the focal point in the painting was a large tree whose roots had been partly exposed as the soil was gradually eroded by episodes of flooding which washed away the soil in such a way as to create a bank with part of the root system right there in plain sight. The parts one couldn’t see, those roots still safely buried in the dark clay, must’ve have been even more complex and far-reaching to be able to support that massive tree.

It took him several days to finish this painting; during that time some local guys had put up camp not far from him to spend a few days fishing on the river. Each day they’d come by to see what he’d done. Fortunately they didn’t say much – the B never could think of explanations when people asked questions. The final day, as he was cleaning up to go home, the good ol’ boys came over to study his work while he gathered up his gear. Finally, one of them pronounced judgement: “that tree don’t belong just to Martin anymore” was his pronouncement.

When the B got home and had finished cleaning up while I studied this amazing work, he told me what they’d said. For me, living with all those scenes he’d “captured”, the comment was a succinct summation of his work. Once on the canvas, that tree, or the river, or the thin light of very early Spring, or the way the light shimmering in the middle distance differed from the sort-of-bluish light emanating from the horizon of some scenes -all of *that* belonged to the viewer.

The whole process has caused me to ponder many times what it means to “see” – I mean the kind of mindful perception where, perhaps, you come to a bend in the road and the lay of the land makes you stand still and simply observe. I call this kind of seeing ‘the aesthetic distance’- that is, you have to stand back enough to take it in but not so far back that you lose whatever it was that captured your attention. Move too close and you’re part of the scene and, again, no longer the observer.

Anyway, the B studied the physiology and anatomy of the eye, needing to understand how it is we see. And he developed his own theories of color along the way, not ever using black or white in his work, though you’d swear those dark shadows must have to contain black. Nope.

His style evolved over the years but he never “fixed” anything: what went on the canvas was never adjusted. He said he could see his mistakes, but I never could. Sometimes when I watched him painting on a blank canvas I was mesmerized: a white square slowly changed as he worked. It seemed as though he was merely removing the opaque white film to reveal what was hidden underneath. This effect was particularly noticeable if you came upon a half-finished work set up to dry at the end of the day.

Painting pictures for a living is a good way to starve so that’s not all he did. I hope he tells you about some of the jobs he had in the “off” season: he didn’t paint once it got too cold to sit out there so he had several months in which to earn money.

(Yes, I worked and paid “my” share of our life together. For a long time, I thought my vocation was to save the world from itself but I finally figured out what I really wanted was to clean its closets. Bringing Order to the world is not the same as capturing Beauty but it has its own immense satisfactions.)

At his shows, people instinctively placed themselves in this aesthetic space. The paintings would hang in rows on the wall, placed at eye level. People would move in close toward the painting to discern the strokes of paint on canvas and then move out to take in the whole scene, and then move in again, trying to figure out how he’d done whatever had captured their attention. As one customer said, “you live with one of these and it changes how you see”.

I have a spot above my fireplace in the living room for one of your landscape paintings. I don’t know if you could ship a painting across the country but I would certainly prefer one of your landscapes to the luridly cartoonish Gustav Klimt print that my daughter presently has adorning the space.

I was also gifted with a similar talent but I squandered it from a lack of discipline to develop it. I now use what is left for technical drawings and architectural plans. I do turn out the occasional cartoon that sums up my pastor’s message, such as an ursine cub hanging by its tail from a branch with the caption “Bear Fruit” inferring that when he is ripe he will drop from the tree into (hopefully) his parents’ waiting arms.

A vocation is far more than just having a gift. In a way, one is compelled to do whatever and doing it has little to do with “lack of discipline” and much more to do with a kind of driven desire. People would say things like, “I wish I had your talent” and he’d say, “it’s not talent. It’s doing something thousands and thousands of times until it becomes second nature”. After all, he began when he was six years old. And when he was finally forced to stop completely, due to blindness, he was still using some of the same equipment he’d been given for Christmas when he was fourteen.

Actually, he didn’t “stop” so much as he was stopped because he could no longer focus well enough to see. I’ve often thought if he could’ve fabricated his own three foot long brush to get past his extreme far-sightedness, and then was able to find a way to immobilize the canvas so it wouldn’t flounder around as his yard-long brush came up against the surface, and could’ve figured out a way to support his arm at that angle, and FINALLY, have patched the eye afflicted with retinal degeneration – why he’d still be painting…

I had a minor gift for drawing cartoons too (I loved Don Martin’s work), but it wasn’t my calling. I enjoyed making people laugh and those elongated arms, huge feet, strange facial expressions, and weird body postures appealed to my rudimentary sense of ‘silly’. Under Martin’s influence I could lighten up a little.

I love your idea of “Bear Fruit”. Wish I’d thought of it.

All you need to be is a punmeister with a vivid cartoonesque imagination. I drew a cartoon that was almost published (I missed the deadline by about three hours) that showed a man behind a counter telling a cloud with lightning coming out of it that it would not be permitted to rain as the aquifer was full. The caption was, “The City of Claremont, which requires municipal permission for everything that occurs within its township, has given new meaning to the phrase, ‘Weather Permitting’.”

Hmmm…maybe we could collaborate. The B’s eyes are gone afa drawing goes. I miss my wonderful b’day cards, anniversary cards, etc. Glad I saved them all.

But sometimes I have an idea (or three) and no one to pitch them to. I haven’t practiced cartooning in a long time…and as you know, if your mind isn’t hobbled by pc you can do some interesting things.

Is Claremont that bad? I pictured it as being California-right … a relative term

No, Claremont is California Left, Upland, our neighbor to the east, is California Right, with a mayor who is unashamedly Christian.

We get along very well as neighbors as we realize that Sacramento’s squabbles are not ours but theirs. Being middle (or upper middle) class means being well-mannered and good neighborly. Lose the state capitol politics and talk about things that matter, such as, “how do we manage our water supply in the face of diminished rainfall?”

Sorry — the few paintings I have left are not for sale. It’s my habit to give them as wedding presents, and since there won’t be any more, I need to save the ones I have for that purpose.

BTW — I love a lot of Klimt’s work. There is an entire gallery dedicated to Klimt in the Belvedere in Vienna, and it includes any number of works I’d never seen before. In his early days he was an Impressionist, and quite accomplished.

I second that; visited the Belvedere year before last, and the Secession building, with Klimt’s “Beethoven Frieze”. As Heinlein (in “Stranger in a Strange Land”) says of Rodin, this was the period just before Western art lost direction: “…the master told stories that laid bare the human heart”.

“…the master told stories that laid bare the human heart”.

And how uncool is that?? In this time of cool so cold that the frozen irony burns and sticks to the tongue, the last thing those in charge want is any possibility of laying bare the human heart.

the print is of a naked woman laying on her stomach holding a bouquet. The Getty had a one-man exhibit as part of their impressionist exhibit. Klimt did much better work and was good and well-practiced at what he did. This was, in my opinion, one of his worst.

Baron, I loved the two landscapes above, especially the colors you used and your way of handling brightness and shade. They are beautiful. Wish you had an attic-ful since I too would love to buy one.

Thank you. 🙂

Don’t worry about the thank yous, just keep the truth coming. Which it has been prophesied shall set us free.